<Tunisia under Ottoman Rule until the Modern Era.

[Spanish Christian

occupations of the Tunisian towns - pogroms and massacres

- Turkish occupation - migrations]

The anarchy which prevailed in North Africa during the late

15th and early 16th centuries facilitated the Portuguese

invasions of Morocco and the Spanish invasion of Algeria and

Tunisia. Only the unexpected intervention of the Ottoman

Turks in the latter two countries finally spared them from

Spanish occupation. In the meantime the menace of

anti-Jewish Spain overshadowed the Tunisian communities.

In 1515 the Spanish fleet raided Djerba and (col. 1441)

the Jews suffered extensively. In 1535 Charles V occupied

Bizerta and La Goulette, their small communities being

expelled or massacred. When the emperor occupied Tunis, he

immediately turned the town over to his soldiers who

ransacked it and massacred 70,000 persons, including a large

number of Jews, while others were sold as slaves.

Several Tunisian ports were taken, liberated, and retaken by

the Spaniards until 1574, when Turkish military victories

finally brought these attacks to an end. As a result of this

climate of insecurity and constant danger, the Jewish

communities of the coast were almost completely depleted of

their members; many of them, natives and Spanish expellees,

left for the orient or Italy.

[Italian havens Pisa and

Leghorn - Leghorn Jews in Tunis - Tunisian native Jews

suspect the immigrated Italian Jews]

When the grand duke of Tuscany called upon the Jews to

establish themselves in his ports of Pisa and Leghorn

[[Livorno]] in 1593, the large number of Conversos and Jews

from various Mediterranean countries who immediately settled

there were joined by African Jews who had already taken

refuge in Italy and sought a permanent home there. Leghorn

thus became a large Jewish center and its trade underwent

considerable expansion. The Jewish community soon sent

representatives to Africa, and from the early 17th century

there was a sizable number of Leghorn Jews in Tunis, where

they were known as "Grana" from the Arab name for Leghorn -

"Gorna".

All the foreign Jews, former Marranos, or Tunisians who,

returned to their native country after spending one or two

generations in Italy were gradually integrated among the

Jews of Spanish or Sicilian origin remaining in Tunisia, as

well as those who had recently arrived from Algeria or

Morocco. In fact, those people who possessed a common

language - Spanish or Italian - customs, and way of life

which were more or less similar were called "Granas" or

"Gornim". From 1685 they designated themselves as "la nation

livornese [from Leghorn] ebrea en Tunes", although many of

them had never set foot in Leghorn.

From the beginning, the Jews known as "Touansa" (natives of

Tunisia), who formed the overwhelming majority of the

community, looked upon the "Grana" with suspicion. Although

both groups lived together in the hara [[Jewish quarter]] for a long time,

their relations continually deteriorated until they bordered

upon hatred.

[17th century-1857:

restrictions of Hamuda Pasha: land possession prohibited -

overcrowded Jewish quarter]

Indeed, in the middle of the 17th century Hamuda Pasha

prohibited all the Jews, whether "Grana" or "Touansa", to

own real estate; they were confined to residential quarters

where they could only be tenants. As a result of

overcrowding, rents soared. The rabbis then decided that

anyone who was the first tenant of a house thus acquired the

right of hazakah

(possession). No other Jew could have the first tenant

evicted by offering a higher rent. The right of hazakah

remained in force for a long time among Tunisian Jews, only

falling into disuse when the government of Muhammad Pasha

authorized the Jews to acquire real estate in the wake of

the Pacte Fondamental of 1857.

[1710-1944: Split between

native Tunisian and immigrated Italian-born Jews]

The decrees which prohibited Jewish ownership of real estate

or confined them to a special quarter were by no means

generally observed in Tunis. In fact, after having coexisted

for several generations the "Touansa" realized that they

were despised by the "Grana", whose religious practices

differed from their own; they subsequently assigned them

special places in their synagogues, as a result of which

life in common became unbearable. The "Grana" finally

separated from their native-born coreligionists completely

and established an independent community which possessed its

own administration, cemetery, slaughterhouses, rabbinical

tribunal, dayyanim

[[judges]], and chief rabbi.

This secession, which occurred in 1710, prevailed until 1899

when the authorities issued a decree calling for an official

merger of the two communities. From that time there was a

single chief rabbi for the whole (col. 1442)

of Tunisia, one rabbinical tribunal and one slaughterhouse

in each town, and a single delegation within the council of

the community and the cabinet of the Tunisian Government. In

practice, however, the schism persisted and the authorities

were compelled to issue a further decree of amalgamation in

1944.

[Expulsion of the

Italian-born Jews from the Jewish quarter by the Tunisian

native Jews - new Jewish quarter and new synagogues - meat

struggle and the meat rules of July 1741 and 1784]

After 1710 the "Touansa" waged a veritable holy war against

the "Grana", going so far as to treat them as false Jews in

light of their pride. They finally succeeded in having them

expelled from the hara

[[Jewish quarter]]. The "Grana" then founded the suq al-Grana, the

commercial artery of the old part of Tunis, and opened three

new synagogues and two houses of prayer, one of which was

situated in the heart of the Christian quarter of that

period.

The struggle between the groups continued and the "Grana" of

Tunis attracted every newcomer in the town to their

community, whether he was of European, African, or Asian

origin. Moreover, their slaughterhouses, which were more

popular, also sold meat to the "Touansa", thus depriving the

ancient community of a part of its meat taxes, raised for

the benefit of its poor. An arrangement became imperative,

and in July 1741 a takkanah

[[rabbinical law unrelated to biblical laws]] was signed by

the rabbis of the two communities under the supervision of

R. Abraham Tayyib, their leader. The following agreements

were reached:

(1) that all Jews who had originated in Christian countries

would form part of the community of the "Grana", while all

those who had originated in Muslim countries would belong to

the community of the "Touansa";

(2) that two-thirds of the general expenses of the community

would be covered by the "Touansa" and one-third by the

"Grana"; and that the "Touansa" could not buy meat in the

"Grana" slaughterhouses.

This prohibition was not observed and had to be renewed in

1784.

[19th century: new

Italian-born Jews influx to Tunisia - equal and distinct

treatment by the government]

The community organization of the Tunisian Jews remained

unchanged for several centuries, with only a single leader,

the qa'id of the

Jews. This leader wielded extensive powers and was

responsible for the collection of taxes - an honorary

position of considerable importance and not lacking in

material advantages. He was generally a member of the

ancient community. Thus, for the most part the "Touansa"

dominated the "Grana". Moreover, the bey regarded both as

his subjects.

This state of affairs was even maintained during the first

half of the 19th century - when there was an intensified

immigration of Leghorn Jews - by the inclusion of a number

of clauses in the treaty signed in 1822 between Tuscany and

the regency of Tunis. In fact, it was anticipated therein

that the Leghorn Jews who settled in the regency would

always be considered and treated as subjects of the country

and would enjoy the same rights as the native-born Jews.

Occasionally, the authorities even adopted policies toward

the ancient community differing from those for the new one,

which was thus discriminated against.

[1686: solidarity of the

Tunisian-born Jews in tax questions and pirate questions]

In 1686 the latter - through the intercession of their

leaders Jacob and Raphael Lombroso, Moses Mendès Ossuna, and

Jacob Luzada - requested a loan from the consul of France in

order to pay a huge tax imposed on them by the Muslim

authorities. They then informed the consul of the extreme

poverty to which the "Leghorn nation" had been reduced. They

claimed that the extortions and assassinations, both past

and present, had impoverished them and that it was their

intention to seek the assistance of their coreligionists of

Leghorn in order to repay the loan which "with tears in

their eyes, they now solicited for the love of God so as to

redeem a nation and a community". Under these circumstances,

as others, the "Touansa" supported the "Grana". Moreover, it

was a rule among the Jews of Tunis to redeem their

coreligionists who had been captured by pirates.

[Rabbis of Tunis: almost

all from the Tunisian-born Jewish group]

There were instances when a single spiritual leader (col.

1443)

headed both communities at the same time. In such a case the

chief rabbi was always a native of the country or a

personality whose ancestors were of African origin. there

was, however, one exception: the renowned talmudist R. Isaac

*Lombroso, who was born in Tunis but was of Leghorn

parentage. His teachers, however, were Tunisians: R. Zemah

Serfati and R. Abraham Tayeb (d. 1714), the famous "Baba

Sidi" who exerted a great influence on the whole of Tunisian

Jewry. The grandson of the latter, also named R. Abraham,

wrote Hayyei Avraham

(1826), a voluminous commentary on the Talmud accompanied by

important notes on *Alfasi, *Rashi, and Maimonides. His son

R. Hayyim Tayeb wrote Derekh

Hayyim (1826) and R. Isaac Tayeb (1830) was

also the author of several valuable works.

The Borjel family were Leghorn Jews of Tunisian origin.

Their ancestor, R. Abraham *Borjel (d. 1795), was a

well-known author and dayyan

[[judge]] in Tunis. Members of this family ranked among the

leaders of Tunisian Jewry for two centuries. The most

famous, R. Elijah *Borjel, simultaneously held the positions

of chief rabbi and qa'id

[[leader]] of the Jews.

From 1750-1850 the Bonan family, Leghorn Jews of African

origin, presided over the destinies of the "Grana", of

Tunis, who were also headed by other Faricans such as

members of the Darmon family.

[Broken fronts between

Tunisian-born and Italian-born Jews by marriages and

Jewish learning]

In the sphere of learning and Jewish studies all enmity

between the two factions disappeared.

The authority of the rabbis of Tunis was very broad: they

supervised the strict observance of religious precepts and

the moral conducts of the individual, also issuing

regulations pertaining to clothing and condemning the fancy

of young women for elegance, jewelry, and fineries. These

rabbis were widely known and were consulted from Erez Israel

and other countries. They were the first to abolish flogging

in Tunis, substituting a heavy fine on behalf of the poor

for it, they also compelled the members of all the

communities to donate one tenth of their annual profits to

charitable and religious institutions. Furthermore, they

encouraged marriage between the "Grana" and the "Touansa".

From the 17th century Tunis became an important center of

Jewish learning: there was a particularly brilliant revival

of the study of Talmud and Kabbalah. H.J.D. *Azulai, who

visited Tunis in 1773, was impressed by the extensive

learning and piety of Tunisian scholars, such as that of his

hosts the Cohen-Tanoudjis family, among whom there

were scholars and qa'ids

[[leaders]]. He also became acquainted with the chief rabbi

of Tunis, R. Mas'ud Raphael al-*Alfasi (d. 1776), author of

the novellae Mishnah

de-Revuta (1805), and his two sons, Solomon (d.

1801) and Hayyim (d. 1783), author of Kerub Mimsha (1859).

In Tunis there were other eminent scholars, such as R.

Uzziel Al-'Haik (*Alhayk), the author of Mishkenot ha-Ro'im

(1760), a rabbinic code in form of an encyclopedia which

deals with every category of problem encountered in the

internal and public life of the Jews of Tunisia during the

17th-18th centuries and thus constitutes a valuable source

of information that is indispensable to the writing of the

history of the Jews of Tunisia. R. Mordecai *Carvalho (d.

1785) was a wealthy merchant in Tunis who devoted a large

part of his life to rabbinical studies. In 1752 he was

appointed rabbi of the Leghorn community and as such was

widely known as a rabbinical authority. Of his works, the To'afot Re'em (1761), a

commentary on the works of R. Elijah *Mizrahi, is the best

known. R. Abraham Boccara (d. 1879), author of Ben Avraham

(1882), was also a leader of the "Grana".

[Tunisian Jews as political

ambassadors and translators for the Turks]

The Jews of Tunisia occasionally played important roles in

diplomatic capacities: in 1699 *Judah Cohen was sent to

Holland as ambassador in order to negotiate a peace and

commercial treaty; in 1702 he was the intermediary between

(col. 1444)

Tunisia and the States General of the United Provinces,

which ratified the secret decisions pertaining to their

relations with the Barbary states. Moreover, Tunisian Jews

were often appointed by the Christian powers to official

positions in the capacity of interpreters or vice-consuls.

In 1814 Mordecai Manual *Noah arrived in Tunis to fulfill

the function of consul of the United States; upon his return

he wrote a work on his travels which includes information on

Tunisian Jews - yet, he never maintained relations with them

as he sought to conceal his Jewish identity. It was,

however, precisely because he was a Jew that the president

of the United States, James Madison, relieved him of his

functions. In a letter which he addressed to the president,

Noah declared that his Jewish identity - when it became

known in Washington - had left an unfavorable impression and

he was therefore asked to leave the U.S. consulate in Tunis.

[Trade questions: higher

taxes for the Jews - articles of commerce]

Their capacity as merchant magnates enabled the Jews of

Tunisia, who were particularly well placed, to redeem

Christian captives. In their trade with France, Italy, and

the Orient these merchants employed bills of exchange, and

controlled the maritime trade in spite of the fact that the

bey imposed higher export and import duties on them than on

the Christians. For the latter the duty was 3% of the value

of the goods, while for Jews it was 10% - reduced to 8% in

the 18th century.

Many Tunisian Jews were treasurers or bankers; they were

employed at the mint; and it was to them that the

authorities assigned the monopolies on fishing of tunny and

corals and the trade in ostrich feathers, tobacco, wool, and

the collection of custom duties.

In 1740 the custom duties of Tunis were leased to the

"Grana" for an annual payment of 80,000 piasters. In 1713

the bey sent a Jew from Bizerta to Sicily to sign a treaty

on coral fishing. By this treaty the Sicilians committed

themselves to bring in their haul of coral to Bizerta, where

it would be sold to the Jews who had signed the treaty. From

the 17th century to 1810 the Jews manufactured over 20,000

shawls of wool or silk in Tunis. More than one half of these

were tallitot

[[sg. tallit, prayer shawl]], which were sent to the

Jews of *Trieste and Leghorn, from where they were exported

to Poland for the religious requirements of the Jews of that

country. The bey defended the interests of the Jewish

merchants.

[1784: War against Venice -

pogroms at Tunis in 1752 and 1756]

In 1784 he declared war on the Republic of *Venice as it had

not indemnified them for the loss of several cargoes in

which the Venetian fleet was involved. Yet, during the same

century the Jews of Tunis were the victims of pillaging on

two occasions: in 1752 by the troops of the bey himself,

when he was deposed from the throne for a time by a

marabout; and in 1756 by Algerian troops who took the lives

of thousands of Muslims and committed the worst outrages on

Jewish women and children.

[since 16th century: craft

professions]

In contrast to the information on the Hafsid period, the

Jews of Tunisia from the 16th century onward engaged in a

variety of crafts. They were clock makers, artistic

ironworkers, shoemakers, and the only ones who worked with

precious metals. They also manufactured musical instruments.

Moreover, many of them were musicians, particularly on

festive occasions. The members of every craft, as well as

the petty tradesmen, were organized in guilds which were

presided over by a Muslim amin

(chief of the corporation) appointed by the authorities.

All controversies between Jewish businessmen,

industrialists, craftsmen, or workers, and all disputes over

salaries, the price charged for the execution of a piece of

work, and the like, were settled by three competent Jewish

colleagues who were designated by their coreligionists.

Occasionally the parties concerned challenged these persons

and demanded the intervention of the amin. The rabbis and

the leaders of the (col. 1445)

community were then compelled to accept his judgment and

enforce it under the threat that a ban would be issued

against the parties involved if they bribed the amin.

[Jewish dresses - "affair

of the hats" because of European-Jewish hats - hat law of

1823]

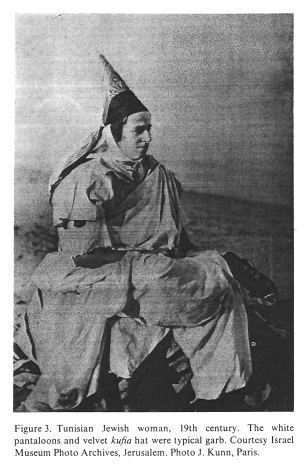

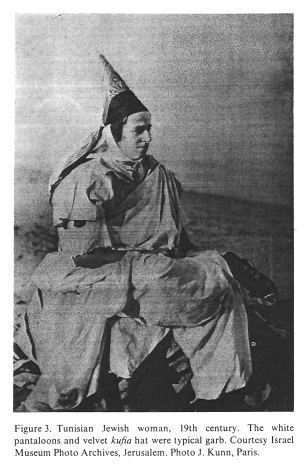

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col. 1436,

Jewish dress in 19th century: Tunisian Jewish woman, 19th

century.

The whiet pantaloons and velvet kufia hat were typical garb.

Courtesy Israel Museum Photo Archives. Photo: J. Kunn, Paris

The native adult Jews of Tunisia wore a kind of small violet

turban which was wound around a black skullcap', while the

remainder of their dress was patterned after the Turkish

fashion. During the 18th century the Leghorn Jews wore hats

and wigs like the Europeans of the West. Until the beginning

of the 19th century the "Grana" and a large number of

"Touansa" merchants had the habit of wearing European

clothes and round hats as a result of their trade, which

required them to stay in Europe for various periods of time.

The authorities shut their eyes to this departure from the

Covenant of Omar. In the end this tolerance gave rise to

abuses when a number of Jews, under the cover of their

European dress, sought to evade certain obligations to which

they were subjected. The bey then decided to compel all the

Jews, whether "Touansa", "Grana", or foreigners, to wear a

cap or a three-cornered hat. This decree was at the source

of the so-called "affair of the hats" which took place in

1823 and almost caused the breaking off of diplomatic

relations between Tunisia and the European states. The

execution of the bey's orders was accompanied by many acts

of cruelty and extortion perpetuated by the officers

responsible for their application.

From the beginning of the [[19th]] century the Jews of Tunis

manifested their approval of the French Revolution, whose

armies emancipated the Jews of Europe in the name of human

rights. They all wore the cockade. One of them who appeared

before the bey with this badge received the bastinado. The

Jews subsequently became ardent supporters of Napoleon and

the "Grana" returned to wearing the French cockade. In order

to restrain them the bey wanted to have one of them burned

alive; he was only saved through the intervention of the

consuls.

[1830-1856: Bey Ahmad

protecting the Jews]

The bey Ahmad (1830-56) treated the Jews favorably on every

occasion. When he visited the king of France, many Jews

formed part of his retinue. He bestowed many honors on his

Jewish private physicians, the baron Abraham Lombrozo, Dr.

Nunez Wais, and the baron Castel Nuevo, who endeavored to

improve the status of their coreligionists. The Muslims

referred to the bey Ahmad as the "bey of the Jews". During

his reign and those of his successors, a large number of

Jews held important positions in his government.

[1855-1859: Bey Muhammad

exempting the Jews from special tasks - execution of Batto

Sfez 1857]

The bey Muhammad (1855-59) abolished the collective

responsibility of the Jews in the sphere of taxation,

exempted them from all degrading tasks, declared that they

would pay the same duties on goods as Muslims and

Christians, and attempted to include them in the common law.

In 1857, however, a Jews, Batto Sfez, who had quarreled with

a Muslim was accused of having blasphemed Islam. The mob

dragged him before the qadi, who condemned him to death. In

spite of a vigorous protest by the consul of France, the bey

Muhammad ratified the sentence and Batto Sfez was executed;

the promises which were given to the consular authorities

and the Jewish population that his life would be spared were

disregarded.

A squadron of Napoleon III's then took up positions in front

of La Goulette so as to coerce the bey to apply the

principles of equality and tolerance toward all the

inhabitants of the regency. The equality of all Tunisian

subjects of every religion was then proclaimed in a kind of

declaration of human rights known as the Pacte Fondamental

(September 1857). All the laws which discriminated against

the Jews were repealed.

[1857-1882: Bey Muhammad

al-Sadiq-Bey: equal rights and taxes for all is not

accepted by the Muslim masses - pogroms 1861-1864 - French

support for the Jews]

In 1861 Muhammad al-Sadiq-Bey (1857-82) promulgated edicts

for drawing up civil and penal codes to be applied by the

newly constituted tribunals. There was widespread discontent

among the Muslim masses as a result of these (col. 1446)

laws. The government was reproached for favoring the

infidels and raising the taxes paid by the Muslims, while

the ministers were accused of having ruined the state. This

was during a period in which the minister of finance, the qa'id Nissim Samama,

contracted onerous loans in Europe.

An insurrection of the tribes broke out. In the north of the

country the ill-treated Jews were convinced that their

salvation only lay in the intervention of European warships,

whose presence indeed restrained the rebels. In the south,

pillaging against the Jews of Djerba and Sfax took place. In

1864 the bey was compelled to abolish the new constitution,

but the abuses which it had suppresses did not reappear. The

bey ordered that the Jewish victims of the insurrection be

indemnified. The International Financial Commission, imposed

on Tunisia in the wake of these financial upheavals,

received the collaboration of the Jews and succeeded in its

mission. From then on the French found in the Jewish

population a very useful instrument for support of its

policy, while the "Grana" remained the champions of the

Italian presence in the country. [[...]]

[19th century: Jewish

population figures]

During the 19th century the Jewish population of the country

was mainly concentrated in the towns: there were 60,000 Jews

in Tunis in 1786, 30,000 Jews in 1815 and only 15-16,000 in

the following years; Jews also lived in Matra, Le Kef,

Nefta, Gafsa, Gabès, Sfax, Sousse, Naloeul, Mahdiya, and

Testour. There were also may Jews in the villages and on the

island of Djerba. The total Jewish population of Tunisia at

the end of the 19th century was estimated by some scholars

as 50,000 persons, by others as 60,000, and still others as

100,000.

[C.CO.]> (col. 1447)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica 1971: Tunisia, sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1430 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1431-1432 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1433-1434 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1435-1436 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1437-1438 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1439-1440 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1441-1442 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1443-1444 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1445-1446 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1447-1448 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1449-1450 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Tunisia, vol. 15, col.

1451-1452 |

^