Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Tunisia 05: French Protectorate 1881-1956

Naturalization quarrel - charity fund - Jewish council and schools - pogroms - Vichy and NS law - recovery since 1945

from: Tunisia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 15

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2010)

| Share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

[since 1881: French Protectorate]

<In 1878 the *Alliance Israélite Universelle founded its first school in Tunis. The French Protectorate, which was established in 1881, brought considerable changes in the material life of the Jewish masses of Tunisia.> (col. 1447)

1900-1968.

POLITICAL ASPECT.

[The quarrel about naturalization]

The establishment of the French Protectorate in 1881, although welcomed by the Jews and inspiring a feeling of relative security, brought little change in their status as subjects of the bey. It was only in 1910 that Jews in Tunisia were able to adopt French citizenship. Thereafter, especially after World War I, authorized naturalizations of individual Jews increased. By the eve of Tunisian independence in 1956, there had been 7,311 naturalizations, which, including children and descendants of the naturalized persons, reached a total of 20,000.> (col. 1447)

<SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS.

[Impoverished Jews in the Jewish quarter - professions of the Jews]

Early in the 20th century the Jewish quarter of Tunis contained a large number of paupers sustained solely by public charity. There was also a considerable number of poverty-stricken individuals with ill-defined occupations. Slightly better off were the artisans, cobblers, and butchers, whose activities were confined entirely to the Jewish quarter. There were also the rich merchants of the Arab souks (bazaars), who were tailors, goldsmiths, and textile merchants. In the European district law clerks and the staff in the big stores were mostly Jewish. There were also many Jews employed in certain banks and enterprises.> (col. 1448)

<COMMUNITY ORGANIZATION.

[Jewish Welfare Fund - community council since 1921]

In the years of the French Protectorate decrees were passed (in 1888, 1899, 1901, and 1913) establishing the Caisse de secours et de bienfaisance israélite de Tunis (Tunisian Jewish Welfare Fund). A similar fund was recognized by the authorities in the other towns under their jurisdiction. In Tunis the fund was administered by a committee composed at first of nine and later 12 officially appointed members. The committee supervised the maintenance of synagogues and the remuneration of rabbis.

In 1921 a community council was formed; followers of the Tunisian ("Touansa") and Portuguese ("Grana") rites were represented proportionately. (In 1944 the "Portuguese" element was eliminated by decree). The council was subdivided into two sections, one dealing with worship and the other with social welfare. It levied taxes on butcher's meat and unleavened bread and was financed by income and donations of synagogues, the sale of cemetery plots, and government subsidies. The chief rabbi could attend all sessions of the council in a consultative capacity. The Jewish community was subsidized by the civil authorities and had an autonomous budget.

Between the two world wars it hat an indirect political role, as it had to appoint a representative of the Jewish population to the section of the Grand Conseil [[main council]].> (col. 1450)

[Schooling]

<EDUCATION.

When the first school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle was opened many Jews registered their children there in order to afford them a combined modern French education and religious education. When large scale free education was introduced, however, a large number of families sent their children to government schools, which were patterned on the French educational system. Middle class Jews regarded education in Alliance Israélite Universelle schools as a retrograde step, as the Alliance only provided elementary education or commercial training. It ran two boys' schools and one girls' school in Tunis and also had one school in Sousse and another in Sfax.> (col. 1449)

[Pogroms 1917, 1932, and 1934]

During World War I many Tunisian Jews fought in the French army. In August 1917 there were rebellions at Bizerta, Tunis, Sousse, Sfax, Kairouan, and Mahdiya, during which Tunisian troops invaded and looted the Jewish quarters.

In 1932 there were new outbreaks in Sfax, and in 1934 in Ariana. On the whole, however, Tunisian Jewry lived peaceably with the rest of the population prior to World War II and were able to achieve rapid emancipation.

[Nov. 1940-Nov. 1942: anti-Jewish Vichy law - Nov. 1942-7 May 1943: NS occupation with taxations, confiscations and fines - concentration camps - allied bombardments - deportations]

Between November 1942 and May 7, 1943, Tunisia was occupied by Nazi Germany. This caused a further deterioration in the condition of the Jews, who had been subject to the discriminatory Vichy laws (see *France, Anti-Jewish Legislation) from November 1940. Upon their arrival the Germans imposed the establishment of a local council (*Judenrat) which was headed by Paul Ghez. The Nazis took hostages, requisitioned property, and imposed heavy fines on the Jewish community. Taxation and confiscation of property was greatest in Djerba, where the Nazis levied a tax of 88 lb. (40 kg.) of gold on the community, and at Sfax, Sousse, and Tunis, where the Great Synagogue was turned into a German stable.

The Nazis also mobilized all Jews between the ages of 18 and 28 and sent some 4,000 of them to labor camps situated on the front line of battle and near airfields. There was a considerable number of (col. 1447)

casualties from intensive Allied bombardment, hygiene was almost nonexistent, and some succumbed to maltreatment.

During this period, there were large roundups of Jews, individual deportations to death camps in Europe, arbitrary local executions, and large-scale plunder.

[since 1945: recovery of Jewish life in Tunisia - preparation of independence]

With the end of the war, intellectual, economic, and social activity was renewed. Jewish newspapers reappeared, Jews entered the public service, and steadily increasing numbers of Jewish students attended French universities. As Tunisia prepared for independence the Jewish population suffered from a slump in the economy, unrest, and relative insecurity. When autonomy was granted in 1954, the attorney Albert *Bessis was appointed a minister. Upon independence President Habib Bourguiba appointed in his place André Barrouch, a Jewish businessman whose financial assistance to the Destour Party was considerable.> (col. 1448)

<SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS.

After World War II, the numerous crises in trade in the bazaars, coupled with possibilities to continue on to a higher education, encouraged the younger generation to abandon the traditional occupations of their parents in favor of the civil service, particularly teaching. Those who graduated from French universities rapidly rose to important posts in medicine and the judiciary.

On the eve of Tunisian independence there were over 100 Jewish physicians and at least double that number of attorneys. In 1946 the active Tunisian Jewish population numbered 19,928 persons, of whom 9,265 were employed in industry, 6,594 in trade, and 1,166 in administration and transportation. Members of the liberal professions numbered 479, and there were 1,048 clerks and 320 officials. None of the above figures relates to French or other nationals, a large number of whom held important posts in banks and the administration and played a leading role in the intellectual life of the country. In 1956, 27.8% of the Jewish quarter's Jewish population (34% of its population was non-Jewish) belonged to the labor force, half of whom were laborers and artisans. On the eve of Tunisian independence, a considerable proportion of the liberal professions was in Jewish hands. There were, however, very few Jewish engineers or qualified technicians.> (col. 1449)

Some photos of Jews in Tunisia of 1953

Jerusalem, Israel Museum Photo Collection, Department of Ethnography

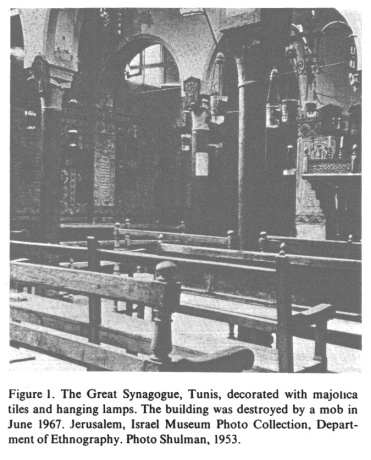

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Tunisia, vol.15, col.1433: The Great Synagogue, Tunis, decorated with Majolica tiles and hanging lamps. The building was destroyed by a mob in June 1967. Photo: Shulman 1953

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Tunisia, vol.15, col.1434: Chief Rabbi Cohen and the treasurer of the Gharība synagogue at Ḥara al-Ṣeghīra, Djerba. Photo: Shulman, 1953

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Tunisia, vol.15, col.1438: The Great Synagogue of Gabès, 1953. Photo: Shulman

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Tunisia, vol.15, col.1440: Jews of Thala in western Tunisia, 1953. Photo: Shulman

[Community]

<On the eve of independence it [[the Jewish community]] had merely a social and religious function, aiding needy Jews and maintaining Hebrew culture. The last Tunis Community Council was elected in 1955.> (col. 1450)

[Schooling]

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Tunisia, vol.15, col.1437: A school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, Tunis, 1953. Photo: Paul Brami, Tunis

<At the time of Tunisian independence, 3,000 pupils attended Alliance schools. In 1957 some 11,761 Tunisian Jewish pupils attended elementary and high schools, 920 attended vocational training school, and 225 were registered for higher education. In that year 159 pupils graduated from high school and 71 from higher studies. These statistics do not cover pupils of French or foreign nationality in the schools surveyed, nor do they include medical students in France or Algiers, as Tunis had no faculty of medicine at that time.

Hebrew was taught only in the Alliance Israélite Universelle schools. The educational reform of 1958, which made Arabic predominant in the curriculum, created a dilemma in the choice of the type of schooling; Jewish parents were divided between the necessity of choosing Arabic instruction for their children and their desire to allow them to continue their French studies in schools that were independent of the Tunisian government. Naturally, the large emigration had serious repercussions on school attendance figures. Only the schools in Djerba preserved their traditional Jewish character, as they had always resisted the penetration of Western culture.> (col. 1449)

<CULTURAL LIFE [[1881-1956]]

[Jewish literature in Judeo-Arabic and French]

As Tunisian Jews were forbidden to write in classical Arabic, they produced an abundant popular literature in colloquial Arabic printed in Hebrew characters, which began to appear in the late 19th century and continued until the 1960s. This body of literature contained over a thousand stories, legends, songs, and laments published in over 50 periodicals. The many authors include Eliezer Farhi, Jacob Cohen, Simha Levy, Daniel Hagège, and Michel Uzan.

The establishment of the first Jewish printing press in Tunis (1882), Djerba (1912), and Sousse (1917) encouraged the distribution of the publications, which were read throughout North Africa from Morocco to Tripolitania. Many rabbinical works by Tunisian rabbis such as Joshua Bessis, Hai Taieb, Solomon Dana, and even by foreign rabbis were also published.> (col. 1449)

[Newspapers and Carthage prize for Jews]

<Between the two world wars a large French-language, Zionist, and independent Jewish press enjoyed a wide circulation; periodicals included La Justice, La défenseur, Le réveil Juif, La Voix Juive, and La Gazette d'Israël. The Prix de Carthage was three times awarded to Tunisian Jews: to "Ryvel" (Raphael Lévy) in 1931 for his novel L'enfant de l'Oukala; to Raoul Darmon in 1945 for his essay "La déformation des cultes en Tunisie"; and to Albert *Memmi in 1953 for his novel La statue de sel.> (col. 1449)

previous next

^