<MADRID (Magerit),

capital of Spain.

[Muslim stronghold -

Christian occupation in 1083]

Mentioned as a Moorish stronghold, it was a tiny town in

the Middle Ages. A small Jewish community existed there in

the 11th century. Most of the Jews there were apparently

merchants during the Muslim period. Nearby was located the

small town of Alluden, whose name is derived from the

Arabic al Yahudyin (al-Yahūdyīn) ("the Jews"). Madrid was

captured from the Muslims by Alfonso VI in 1083.

The Community's Status.

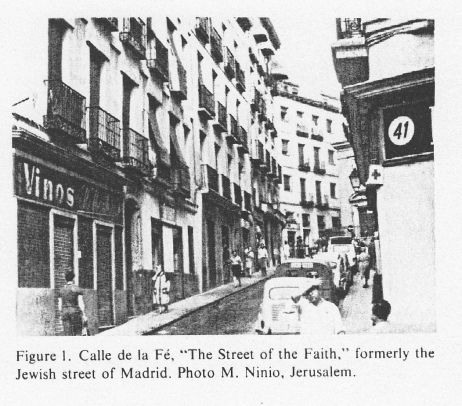

The community began to flourish during the 13th century,

the Jewish quarter being located on the present Calle de

la Fé ("Street of the Faith").

The synagogue, which was destroyed during the persecutions

of 1391 (see below), was situated next to the church of

San Lorenzo. In 1293 a copy of the resolutions passed by

the Cortes in Valladolid was sent to Madrid, in which

Sancho IV ratified a series of restrictions concerning the

Jews. They were barred from holding official

positions, the rate of usury they were permitted to charge

was defined, and they were prohibited from acquiring real

estate from Christians or from selling them properties

already acquired, among other limitations.

In 1307, when Ferdinand VI confirmed these prohibitions at

the Cortes in Valladolid, a copy of them was passed to

Madrid. They were endorsed by Alfonso XI in 1329. A

directive from the time of *Asher b. Jehiel (early 14th

century) permitting action to be taken against an

*informer who had harmed the community is extant (Asher b.

Jehiel, Responsa, Constantinople (1517), ch. 17, no. 6).

The Jews of Madrid owned goods and real estate in the town

and its environs. In 1385 John I acceded to the request of

the Cortes and delivered a copy of its resolutions to

Madrid. He then imposed a series of restrictions

concerning the relations between Jews and Christians,

prohibiting Jews from holding official positions,

canceling debts owed them by Christians for 15 months, and

abrogating the right to acquire stolen goods, among other

regulations.

Persecutions and

Expulsion. [massacres and conversions in 1391 -

impoverished new community]

The persecutions of 1391 were disastrous for the Madrid

community. Most of its (col. 682)

members were massacred, some adopted Christianity, and

community life came to an end. The municipal authorities,

in a report sent to the Crown, complained of the

pueblo menudo

("little people") who continued the rioting and pillaging

for a whole year. Several of the rioters were arrested and

tried, but many escaped justice. Apparently the community

was later reestablished, although it was greatly

impoverished.

[Confirmed compulsive

badge - job restrictions]

During the early 1460s, *Alfonso de Espina preached in

Madrid against the *Conversos. It was there that he turned

to *Alfonso de Oropesa, the head of the Order of St.

Jerome, to enlist his support in eradicating judaizing

tendencies among them. In 1478 the municipal council

complained that the Jews and the Moors there were not

wearing a distinctive sign (*badge). The Crown answered

the complaint on November 12 and ordered that the

offenders should be punished in the prescribed manner. On

February 2, Ferdinand and Isabella renewed the restriction

issued by John II in 1447 which prohibited the Jews of

Madrid from trading in foodstuffs and medicaments and from

practicing as surgeons.

[Expulsion of Spain in

March 1492]

No details are known as to how the community fared after

the decree of expulsion of the Jews from Spain was issued

in March 1492. However, on Oct. 7, 1492, Ferdinand and

Isabella ordered an investigation into reports of attacks

on local Jews by various persons who had promised to

assist them in reaching the frontiers in order to go to

the kingdoms of Fez and Tlemcen. On Nov. 8, Fernando Nuńez

Coronel (Abraham *Senior) and Luis de Alcalá were

authorized to collect the debts still owing to Jews.

The Conversos. [show

trials in Madrid (autos-da-fé)]

Several Conversos of Madrid were tried by the Inquisition.

They were at first tried in Toledo; however, in 1561 when

Madrid became the capital of the kingdom during the reign

of Philip II, the supreme tribunal of the kingdom was

established there and subsequently numerous *autos-da-fé

were held in the city. During the 17th century, many

Portuguese Conversos were tried there and one of the large

autos-da-fé in this period has been painted by Rizzi de

Guevara. During the 1630s, Jacob *Cansino negotiated with

the Conde-Duque de Olivares concerning the possible return

of the Jews to Madrid, after the example of the Jewish

community in Rome. However, the talks had no results

because of opposition from the Inquisition.

Throughout this period, Madrid was the principal center of

the activities of the Portuguese Conversos, several of

whom were connected with the court, while others developed

diversified business enterprises and maintained relations

with the Converso centers outside the Iberian Peninsula.

(col. 683)

The Reestablished

Community. [constitution of 1869 - Jews from North

Africa - Jews from Europe - community since 1920 -

refugees of WWI - refugees from NS territories].

Jewish settlement in Madrid was gradually renewed from

1869, with the conferment of the constitution and the

arrival of Jews from North Africa, who were joined by

Jewish immigrants from Europe. However, it was only during

the 1920s that a community was organized. During World War

I, Madrid gave asylum to a number of refugees, and Max

*Nordau and A.S. *Yahuda, who lectured there in Semitic

philology, lived there during this period.

Among the first Jews to settle in Madrid was the Bauer

family, whose members played an important part in the

organization and development of the community. The law of

1924 which granted citizenship to individuals of Spanish

descent encouraged the further development of the

community, and in the early 1930s there was an addition of

refugees from Nazi Germany. During the Spanish Civil

War, the community underwent much suffering and most of

its members dispersed.

[Cultural life and

institutions in Madrid]

In 1941, the Arias Montano Institute for Jewish Studies

was founded and a department of Jewish studies headed by

Professor Francisco Cantera-Burgos was organized within

the University of Madrid. It was later headed by Professor

F. Perez Castro. Madrid also gave asylum to war refugees,

who were supported by the *American Jewish Joint

Distribution Committee. After the war, the community began

reorganization. A synagogue was founded in Calle del

Cardinal Cisneros. In 1958, a Jewish center with a

synagogue was opened. In 1959, while the representative of

the World Sephardi Federation, Yair Behar Passy, was

visiting Madrid, an exhibition of Jewish culture in Spain

was held at the National Library of Madrid.

An Institute for Jewish, Sephardi, and Near Eastern

Studies was founded jointly by the Higher Council for

Scientific Research and the World Sephardi Federation in

1961. (In 1968 the institute amalgamated with the Arias

Montano Institute). Within the framework of the institute,

the first symposium on Spanish Jewry was held in Madrid in

1964. Leaders of the Madrid community in the late 1960s

included A. Bauer, H. Cohen, L. Blitz, and M. Mazin (the

president of the community).

In that year [[1964]] the community numbered over 3,000.

It served as a center for Jewish students from abroad

coming to study in Madrid. Some Jewish immigrants from

North Africa have been integrated within the Madrid

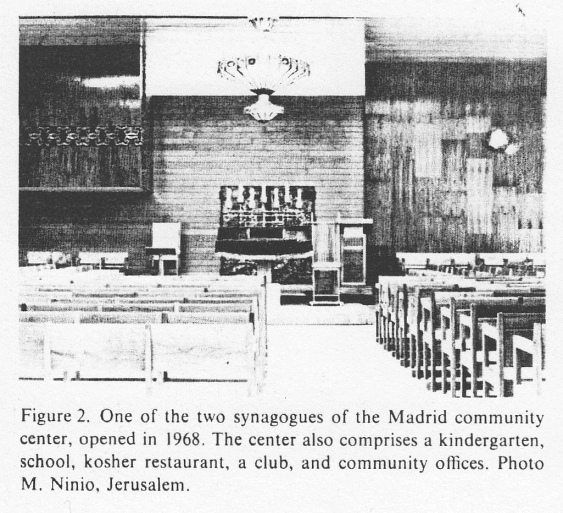

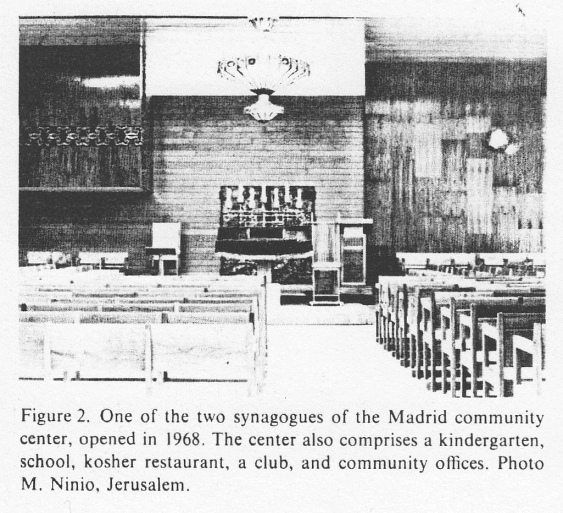

community. In 1968 the community inaugurated its new

communal center and synagogue.

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Jews in Madrid, vol. 11, col.

683, synagogue inaugurated in 1968: One of the two

synagogues of the

Madrid community center, opened in 1968. The center also

comprises a kindergarten, school, kosher restaurant,

a club, and community offices. Photo: M. Ninio,

Jerusalem.

Dr. B. Garzon was appointed first rabbi of the community,

which had a recognized school and a Jewish scout movement.

See also *Spain.

[H.B.]

Bibliography

-- Baer: Spain, 2 (1966), index

-- Baer: Documents (orig. German: "Urkunden"), 2 (1929),

index

-- Fita; in: Bulletin of History Academy of Madrid (orig.

Spanish: "Boletín de la Academia de la Historia"), Madrid,

8 (1885), 439-66

-- F. Cantera: Spanish synagogues (orig. Spanisch:

"Sinagogas espańolas") (1955), 241-2

-- R.T. Davies: Spain in Decline (1957), 76-77

-- AJYB [American Jewish Year Book], 63 (1962), 318-22

-- J. Gomez Iglesias (ed.): Law in Madrid (orig. Spanisch:

"El Fuero de Madrid") (1963)

-- Suárez Fernández: Documents (Span.: Documentos), index

-- Ashtor: Korot, 2 (1966), 145

-- H. Beinart: Ha-Yishuv ha-Yehudi he-Ḥadash bi-Sefarad

(1969).> (col. 684)