<Beginning of the

Christian Reaction.

[Influence by Raymond de

Peñaforte - limited Jewish rights - forced conversions -

blood libels]

However, early in the 13th century, a Christian reaction

made itself felt, under the influence of *Raymond de

Peñaforte, Dominican confessor to the king. From Barcelona

he attempted to limit the influence of the Jews by fixing

the interest rate on moneylending at 20%, by limiting the

effectiveness of the Jewish oath, and restating the

prohibition on Jews holding public office or employing

Christian servants (Dec. 22, 1228). The Council of Tarragona

(1235) restated these clauses and forbade Muslims to convert

to Judaism or vice versa. The Cortes increased their

attempts to suppress Jewish moneylending.

Thus the climate had changed.

[[It can be that their was also a bad influence from the

crusader states

which were more and more lost. The climate had changed in

big parts of Central and Western Europe already 200 years

before with the beginning of the crusades]].

Following the example of France, the kingdom of Aragon

initiated a large-scale campaign to convert the Jews through

exposing the "Jewish error". From 1250 the first blood libel

was launched in Saragossa.

Soon the example of Louis IX found Spanish (col. 230)

imitators: James I found himself obliged to cancel debts to

Jews (1259). Soon after, an apostate Jew carried over to

Spain the work of Nicholas *Donin of France, provoking a

disputation between Pablo *Christiani and the most famous

rabbi of the day, *Nahmanides. Held before the king, the

bishops, and Raymond de Peñaforte, the disputation took

place in Barcelona on July 20, 27, 30, and 31, 1263 (see

*Barcelona, Dispuation of). Central to the disputation were

the problem of the advent of the Messiah and the truth of

Christianity; probably for the last time in the Middle Ages,

the Jewish representative secured permission to speak with

complete freedom.

After a somewhat brusque disputation, each side claimed the

victory. This constituted no check to Christian missionary

efforts; forced conversion remained prohibited but the Jews

were compelled to attend conversionist sermons and to censor

all references to Jesus or Mary in their literature.

Nahmanides, brought to trial because of his frankness, was

acquitted (1265), but he had to leave Spain and in 1267

settled in Jerusalem.

[1267: Papal bull gives way

to the first inquisition - lost crusader states - the

useful colonizers are restricted]

By his bull

Turbato corde

[[1267]], proclaimed at this time, Pope Clement IV gave the

Inquisition virtual freedom to interfere in Jewish affairs

by allowing the inquisitors to pursue converted Jews who had

reverted to their old religion, Christians who converted to

Judaism, and Jews accused of exercising undue influence over

Christians and their converted brethren.

[[Supplement: The inquisition movement since 1267 also has

to be seen in the context of the lost racist crusader states

in Palestine. It's a revenge of the racist church against

all other belief to keep the power after the defeat in the

Middle East]].

It was becoming apparent that the Jews had outlived their

usefulness as colonizers, except in southern Aragon. The old

hostility toward Judaism reappeared, but for the time being

was content with efforts to convince the Jews of the truth

of Christianity.

At this period Raymond *Martini, one of the opponents of

Nahmanides, published his

Pugio

Fidei, a work which served as the basis for

anti-Jewish campaigns for many years. But the economic

usefulness of the Jews was still considerable: in 1294

revenue from the Jews amounted to 22% of the total revenue

in Castile. In spite of mounting hostility on the part of

the burghers, the state was very reluctant to part with such

a valuable source of income.

[Christian middle class

confronts the Jewish quarter - the Jewish community life

with an own jurisdiction - the development of a rotation

system in the Jewish councils]

The very existence of the Jewish communities posed problems

for the burgher class. The aljama [[Jewish quarter,

synagogue]] was a neighbour of the Christian municipality

but was free from its authority because of its special

relationship with the king. The

judería [[Jewish quarter]] (col. 231)

thus often seemed to be a town within a town. The aljama

itself in this period reinforced its authority and closed

its ranks, limiting the influence of the courtiers, who were

increasingly becoming a dominant class with no real share in

the spiritual life of the people.

The different communities in Aragon had developed on

parallel lines without any centralized organization. At

times their leaders met to discuss the apportionment of

taxes, but this had never led to the development of a

national organization. Within the communities the struggle

continued between the strong families who wielded power and

the masses.

In general the oligarchy succeeded in dominating the

communal council with the assistance of the

dayyanim [[judges]]

who, since they were not always scholars, had to consult the

rabbinical authorities before passing judgment according to

Jewish law.

Around the end of the 13th century the

dayyanim began to be

elected annually, the first step toward greater control by

the masses. Soon after, these masses managed to secure a

rotation of the members of the council, but nevertheless

these were nearly always chosen from among the powerful

families.

[Kabbalistic movement under

Nahmanides - and philosophic controversy about Maimonides

again - Jews at Christian courts are decreasing]

Such a climate of social tension, aggravated by the anxiety

caused by the insecure state of the Jews, proved fruitful

for the reception of kabbalistic teachings, transplanted at

the beginning of the 13th century from Provence to Gerona.

Mainly due to the works of Nahmanides, the kabbalistic

movement developed widely (see *Kabbalah). Between 1280 and

1290 the Zohar appeared and was enthusiastically received.

Philosophy appeared to be in retreat before this new trend.

At this very moment the Maimonidean controversy broke out

once more, beginning in Provence where the study of

philosophy had received a new impetus through the

translations of works from Arabic by the Ibn *Tibbon and

*Kimhi families. The quarrel reached such dimensions that

the most celebrated rabbi of the day, Solomon b. Abraham

*Adret, rabbi of Barcelona, was obliged to intervene. A

double

herem [[ban

sentence]] was proclaimed on those who studied Greek

philosophy before the age of 25 and on those who were too

prone to explain the biblical stories allegorically.

Exceptions were made on works of medicine, astronomy, and

the works of Maimonides.

This ban was probably another sign of the decline of the

Jewish community of Aragon and its increasing tendency to

withdraw into itself. During the same period Jewish

courtiers lost their influence and left the political arena.

[Castile: Lasting Jews at

court - expulsion plan of Martínez de Oviedo fails - rabbi

Asher b. Jehiel in Toledo]

In Castile, on the other hand, Jewish courtiers continued to

play an important role in spite of the efforts of other

courtiers to be rid of them and of the Church to condemn

them as usurers. Apostates were to the fore in this

struggle, especially *Abner of Burgos who, becoming a

Christian in 1321 and taking the name Alfonso of Valladolid,

tried to remain in close contact with the Jewish community,

the better to influence it.

Around the same period, Gonzalo *Martínez de Oviedo,

majordomo [[mayordomo, Engl.: administrator, butler]] to the

king, obtained the temporary dismissal of Jewish courtiers

and planned the eventual expulsion of all the Jews of the

kingdom. Soon himself accused of treason, he was put to

death (1340) and his plan fell into abeyance.

At the beginning of the 14th century *Asher b. Jehiel became

rabbi of Toledo, the principal community in the kingdom,

holding this office from 1305 to 1327. After the

imprisonment of his master *Meir b. Baruch of Rothenburg, he

had been the leading rabbinic authority in Germany, a

country he fled from in 1303. Practically as soon as he

arrived in Spain he was involved in the philosophic

controversy and signed the ban proclaimed by Solomon b.

Abraham Adret. On the latter's death he became the leading

rabbinic scholar in Spain, where he disseminated the methods

of the tosafists and the ideals of the *Hasidei Ashkenaz.

(col. 232)

[No Black Death expulsions

in Castile - Jews at the court of Pedro the Cruel -

synagogue in Toledo of 1357]

The attitude of the Catholic monarchy toward the Jews

continued to vacillate. Alfonso XI resolved to root out

Jewish usury but to permit the Jews to remain (1348). The

*Black Death, which reached Spain at this period, did not

give rise to persecutions like those which swept central

Europe.

Alfonso's successor, Pedro the Cruel (1350-69) brought

Jewish courtiers back into his employment and allowed Don

Samuel b. Meir ha-Levi *Abulafia, his chief treasurer, to

build a magnificent synagogue in Toledo in 1357 (it was

later turned into a church and subsequently into a museum).

Despite the fall of Don Samuel, who died in prison, other

Jewish courtiers retained their positions and influence.

[Castile: Civil war - Pedro

is "the king of the Jews" - restrictions in Burgos -

Henry's victory - Jewish positions - Jewish badge]

During the civil war between Pedro and his bastard

half-brother, Henry of Trastamara, the Jews sided with the

king, who, therefore, was even called the king of the Jews.

When Burgos was taken by the pretender (1366), the Jewish

community was reduced to selling the synagogue appurtenances

to pay its ransom. Some of its members were even sold into

slavery.

Henry's victory, augmented by the capture of Toledo (in

which many Jews fell victim), reduced the local community to

destitution: the king had seized at least 1,000,000 gold

maravedis. However, this did not prevent the king from

appointing Don Joseph *Picho as tax farmer and other Jews

from filling important positions. Incited by the Cortes, he

imposed the Jewish badge and forbade Jews to take Christian

names, but he did not dismiss his Jewish courtiers.

[Castile since 1380:

Restrictions for the Jewish jurisdiction]

Meanwhile the condition of the Jews in the kingdom

deteriorated. In 1380 the Cortes, as a result of the secret

execution of Don Joseph Picho as an informer on the orders

of the rabbinical tribunal, forbade the Jewish communities

to exercise criminal jurisdiction and to impose the death

penalty or banishment.

[Castile: Asher family]

In Castile the first part of the 14th century was dominated

by the personality of *Jacob b. Asher, third son of Asher b.

Jehiel, who was dayyan [[judge]] in Toledo. Around 1340 he

published his

Arba'ah

Turim, a codification of the law combining the

Spanish and the Ashkenazi traditions, which was widely

distributed. His brother *Judah b. Asher succeeded his

father in Toledo and became in effect the chief rabbi of

Castile.

[Kingdom of Aragon: no Jews at the court -

royal protection - Jewish taxes by Jewish business -

Inquisition - no forced conversions]

The situation in Aragon was generally both less brilliant

and less disquieting. There the influence of the Jews at

court had practically disappeared with the dismissal of the

Jewish courtiers. The Jews were tolerated and had the right

to royal protection within the limits of Church doctrine on

the matter. The taxes raised from the Jews were an important

source of revenue and so they were allowed to pursue their

commercial ventures and direct their own internal affairs.

Under the reign of James II (1291-1327) the Inquisition had

begun to show an interest in the Jews but the king declared

that their presence was an affair of state and not a

religious concern, an attitude characteristic of the

monarchy for many years. James gave no assistance to the

efforts to convert the Jews. When the *Pastoureaux arrived

in Aragon the king resisted them vigorously in his efforts

to spare the Jews from this menace.

[Kingdom of Aragon: Jewish

influx from France - Black Death persecution with pogroms

and massacres - measures]

During his rule (1306) Jews expelled from France were

permitted to settle in Spain. Unlike in Castile, in Aragon

the Black Death gave rise to anti-Jewish excesses. In

Saragossa only 50 Jews survived and in Barcelona and other

Catalonian cities the Jews were massacred. So shattered were

the communities by these riots that their leaders convened

in Barcelona in 1354 to decide on common measures to

reestablish themselves. They resolved to establish a central

body to appeal to the papal curia to defend them against

allegations of spreading the plague and to secure for them

some alleviation in their situation. A delegation sent to

Pope Clement VI in Avignon succeeded in having a bull

promulgated which condemned such accusations.

[Kingdom of Aragon: Jewish

community life and developments]

It would seem that the attempt to create a central (col.

233)

organization did not succeed, but the Aragon communities had

nevertheless to reorganize. From 1327 the Barcelona

community succeeded in abolishing all communal offices which

were acquired by royal favour. Authority and power within

the community were henceforth vested in the Council of 30,

elected by the community notables. The 30 were trustworthy

men, judges or administrators of charities, who were

empowered to issue

takkanot

[[sg. takkanah, major legislative enactment]] and apportion

taxes. They were elected for three-year terms and could

serve more than one term; however, close relatives could not

sit on the same council.

Although in effect the aristocracy remained in power, they

were no longer all-powerful. The presence in Barcelona of

eminent masters of the law counterbalanced the ambition of

the powerful families. Nissim b. Reuben *Gerondi (d.c.

1375),

av bet din

[["Father of the House of Justice"]] in Barcelona, exercised

great influence over all Spanish Jewry, as attested by his

many responsa (the majority of which are unfortunately no

longer extant). Hasdai *Crescas, born in Barcelona around

1340, who seems to have been close to court circles, became

the most venerated authority in Spanish Jewry. *Isaac b.

Sheshet Perfet, also born in Barcelona (1326), rapidly

became known as a leading rabbinic authority. A merchant by

trade, he later served as rabbi in various communities.

[2 April 1386: New

structure of the Jewish council of Barcelona]

On April 2, 1386, Pedro IV approved a new constitution for

the Barcelona community which constituted a slight progress

toward democratization. The community was divided into three

classes, almost certainly according to their tax

contribution. Each class was empowered to nominate a

secretary and elect ten members of the council. With the

secretaries, the 30 elected members made up the grand

council of the community. Five representatives of each class

and the secretaries constituted the smaller council. The

secretaries served for one year only and could only be

renominated after two years had expired.

One-third of the 30 members had to be renewed each year. The

council had limited powers only, being unable to establish

tax allocations without the approval of the 30. Tax

assessors had to be chosen from among the three classes. The

influence of the powerful families was thus curbed,

extending only over the class of the community of which they

were members.

[Jewish councils of little

communities]

The smaller communities, of course, established a less

complex system of administration. Councils were not

appointed there until the second half of the 14th century.

In many places the local oligarchy seems to have maintained

its power. In Majorca, essentially a mercantile community,

this oligarchy was composed of merchants who prevented any

democratization of the administration. The royal

administration recognized the existence of

judíos francos [[French

Jews]], descendants of courtly Jewish families who paid no

taxes to the community and took no part in communal life.

They married among themselves and generally remained true to

their faith.

[Religious control of the

Jewish communities in Spain]

The communities were also concerned with the moral life of

their members. An institution almost unique to Spain in the

Middle Ages was the

*berurei

averah, notables who watched over the religious

life of their communities. The latter also exercised

authority over *informers, punishing them with loss of a

limb or death, with the approval of the king. The death

sentenced was generally carried out immediately, which

to some seemed dangerous or arbitrary. To avoid the

possibility of abuse, in 1388 Hasdai Crecas was appointed

judge over all informers in the kingdom.> (col. 234)

The Persecutions of 1391.

[Kingdom of Castile:

anti-Jewish sermons - pogroms, fires and massacres under a

child king]

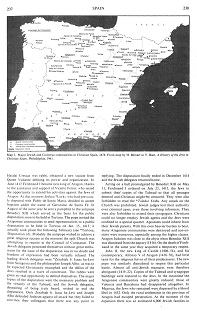

Soon the face of Spanish Jewry was brutally altered. In 1378

the archdeacon of Ecija [[between Seville and Córdoba]],

Ferrant *Martinez, launched a campaign of violent sermons

against the Jews, demanding the destruction of 23 local

synagogues. On the death of the archbishop in 1390, he

became virtual ruler of the diocese, using this situation to

intensify his anti-Jewish campaign and declaring that even

(col. 234)

the monarchy would not oppose attacks on the Jews.

After unsuccessful interventions by the communities, the

death of King John I of Castile (1390) left the crown in the

hands of a minor who did not attempt to check the

redoubtable preacher. On the first of Tammuz 5151 (June 4,

1391) riots broke out in Seville. The gates of the judería

[[Jewish quarter]] were set on fire and many died. Apostasy

was common and Jewish women and children were even sold into

slavery with the Muslims. Synagogues were converted into

churches and the Jewish quarters filled with Christian

settlers.

Disorder spread to Andalusia, where Old and New Castile

Jewish communities were decimated by murder and apostasy. In

Toledo, on June 20, Judah grandson of Asher b. Jehiel,

refused to submit and was martyred. Attacks were made in

*Madrid, *Cuenca, Burgos, and Córdoba, the monarchy making

no efforts to protect the Jews. So many people had been

involved in the riot that it proved impossible to arrest the

leaders.

In July violence broke out in Aragon; the Valencia community

was destroyed on July 9 and more than 250 Jews were

massacred. Others, including Isaac b. Sheshet Perfet,

managed to escape. The tardy measures taken by the royal

authorities were useless.

Many small communities were converted en masse. In the

Balearic Islands the protection of the governor was to no

avail: on July 10 more than 300 Jews were massacred. Others

took refuge in the fortress, where pressure was put on them

to compel them to (co. 235)

convert. A few finally escaped to North Africa. In Barcelona

more than 400 Jews were killed on August 5. During the

attack on the Jewish quarter of Gerona on August 10 the

victims were numerous. The Jews of *Tortosa were forcibly

converted. Practically all the Aragon communities were

destroyed in bloody outbreaks when the poorer classes,

trying to relieve their misery by burning their debts to the

Jews, seized Jewish goods. Yet the motive behind the attacks

was primarily religious, for, once conversion was affected,

they were brought to an end.

[King John I of Aragon lets

the pogroms go - the "Christians" take over the Jewish

positions]

Although he did not encourage the outbreaks, John I of

Aragon did nothing to prevent or stop them. contenting

himself with intervening once the worst was over. Above all

he was concerned to conserve royal resources and on Sept.

22, 1391 ordered an enquiry into the whereabouts of the

assets of the ruined communities and dead Jews, especially

those who had left no heirs. All that could be found he

impounded.

At this point Hasdai Crescas became in effect the saviour of

the remnants of Aragonese Jewry, gathering together the

funds necessary to persuade the king to come to their

defense, appealing to the pope, and offering assistance to

his brethren. The assassins were barely punished, but when a

fresh outbreak seemed imminent early in 1392 the king

swiftly suppressed it. Subsequently he took various measures

to assist Hasdai Crescas in his efforts to reorganize the

communities and reunite the dispersed members.

Meanwhile, in Barcelona and Valencia, the burghers, freed

from their rivals, seemed opposed to the reconstitution of

the shattered Jewish communities. A small community was

reestablished in Majorca. In the countryside the communities

could reorganize more easily; there the Jews were

indispensable and less a target of the jealousy of the

Christian burghers.> (col. 236)

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol.15, col.235, convicted Jew by inquisition with sanbenito: Victim of the Inquisition wearing the sanbenito,