Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Spain, vol. 15, col. 220 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Spain, vol. 15, col.

221-222 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

223-224 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

225-226 |

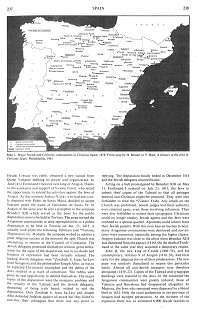

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

227-228 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

229-230 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

231-232 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

233-234 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

235-236 |

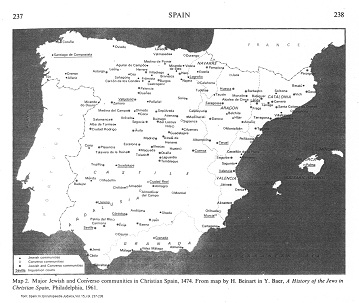

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

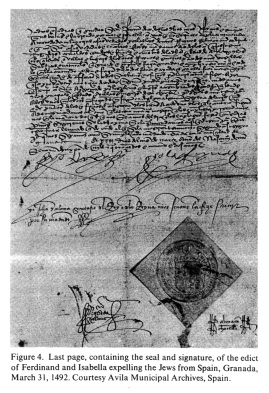

237-238 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

239-240 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

241-242 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

243-244 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol. 15, col.

245-246 |

|

|

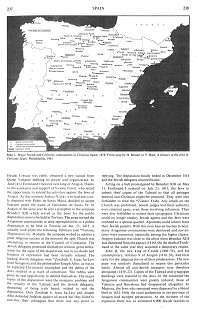

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Spain, vol.15, col.237-238, map of the Jewish communities of 1474

previous

previous