Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in the "USA" 01: until 1820

Natives never mentioned - Jews in the New England States - discrimination habits by the Protestants - revolution of 1776 - Jewish professions in the early national period 1776-1820 - acculturated Jews

from: Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): USA; vol. 15

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

[[...]]

[Jewish colonialism in the New England Territories]

[[The Indian natives which were driven away and mostly exterminated are never mentioned in Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

[Professions]

Jewish businessmen soon helped launch huge enterprises in the trans-Allegheny West involving millions of aces. None of the proposed colonies in which they were concerned proved successful, but they did help in opening the West to American settlers.

The typical Jewish shopkeeper was an immigrant devoted to Judaism. The kehillah [[congregation]] he established was a voluntaristic one, yet compulsion was built in. The recalcitrant Jew had nowhere else to turn. Discipline, especially in matters of kashrut [[Jewish nutrition rules]], was constantly exercised but was always ameliorated by the need not to offend. There were too few Jews. Permanent cemeteries were established in 1678 at Newport, and in 1682 at New York. Religious services which had begun in New Amsterdam in 1654 or 1655 were revived in New York not later than the 1680s.> (col. 1589)

[Discrimination of other religions by the "Christian" Protestant majority]

<The early colonial settlers in America brought with them the old stereotype of the Jew as the mysterious outsider, heretic, and despoiler. These prejudices, however, were rarely translated into direct anti-Jewish actions. The very first Jewish settlers in New Amsterdam in 1654 did face an immediate threat when Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor, attempted to expel them. Overruled by the Dutch West India Company, Stuyvesant was forced to grant them the right of residency, and by 1657 they were granted the status of burghers. Nevertheless, the Jews remained in effect second-class burghers even after the British took control of New York [[New Amsterdam was renamed New York]]. Although economic rights were secured by the end of the 17th century, political rights were not fully granted throughout the colonial period.

The need for immigrants, particularly those with economic skills, and the growing ethnic and religious diversity of the American colonies were powerful factors counteracting traditional prejudices. Still, each colony had an established church and, consequently, Jews, Catholics, and Protestant dissenters were all subject to discrimination. IN 1658 Jacob Lumbrozo, a physician, the first Jewish settler in Maryland, was charged with blasphemy in that colony, but the prosecution was never completed. In no colony, however, were Jews physically harmed for religious motives, as were Quakers and Baptists, and no 18th-century law was enacted for the sole purpose of disabling Jews. Colonial American Jewry achieved a considerable degree of economic success and social integration, and intermarriage was frequent by the mid-18th century.> (col. 1648)

[Community life: congregations and their structures]

The typical colonial congregation had a parnas [[communal leader]] and a board (mahamad [[executive committee]] or junta). Sometimes there was a treasurer (gabbai), but no secretary. New York had first-class (yehidim (yeḥedim)) and second-class members. No congregation in North America had a rabbi until 1840, but each employed a hazzan (ḥazzan) [[cantor]], shohet (shoḥet) [[ritual slaughterer]], and shammash [[salaried servant in a synagogue]]. On occasion the first two offices, and that of mohel [[ritual expert in circumcision]] too, were combined in one individual.

A sizable portion of the budget, in New York, at least went for "pious works", charities, Itinerants were constantly arriving from the Islands, Europe, and Palestine, and were usually received courteously and treated generously. Once in a while a Palestinian "emissary" would arrive seeking aid for oppressed Jews in the Holy Land. Impoverished members of the congregation were granted loans to tide them over, the sick and dying were provided with medicine, nursing, and physicians; Respectable elders who had come upon hard times were pensioned, and the community itself saw to all burials. There is no conclusive evidence that a separate burial society functioned anywhere in British North America.

Education was not a communal responsibility except for the children of the poor. Rebbes, private teachers, were always available. By 1731 a school building had been erected in New York by a London philanthropist. At first the curriculum consisted only of Hebraic studies to train the boys for bar mitzvah [[day of religious maturity of Jewish boys and girls]], but by 1755 the school had become a communally subsidized all-day institution also teaching secular subjects. The instruction was by no means inadequate; Gershom *Seixas, the first native-born American hazzan (ḥazzan) [[cantor]], received his education in this school.

There were surprisingly few anti-Jewish incidents in the North American colonies [[New England States]]. A cemetery was desecrated now and then, "Jew" was a dirty word, and the press nearly always presented a distorted image of Jewish life both in the colonies and abroad. Despite the fact that Jews were second class citizens, physical anti-Jewish violence was very rare. Rich Jews like the Lopezes and the army-purveying *Frankses were highly respected. They were influential even in political circles.

[Integration and discrimination - acculturated to racism - intermarriages]

Jews were accepted in the English North American settlements because they were needed. Men, money, and talent were at a premium in that mercantilistic age. It was not their Christian interest in the Hebrew Bible which led Protestants to tolerate Jews. Christian Hebraists were enamored of Hebrew, but not of Hebrews or their descendants. Hebraism was an integral part of Christian culture. In this pioneer land Jews were welcomed as business partners. At one time or another most Jewish merchants had worked closely with Christian businessmen. Many of these Jews had intimate Christian friends. Children of the wealthy went to college where they were made welcome, but on the whole the Jews showed little interest in formal higher education. Careers in law were closed, while medicine, apparently, had little appeal. Jews (col. 1589)

typically dressed, looked, and acted like gentiles. They were completely acculturated [[to racism against the natives]]. Away from the community and its rigid controls many of the younger generation flouted the traditional observances and dietary laws.

Social intimacies led to *intermarriage. Practically every Jew who permanently settled in Connecticut married out of the faith and most of them assimilated completely. Intermarriages even in the larger towns of the country were not unusual. The desire for low visibility induced the Sephardi hazzan (ḥazzan) [[cantor]], Saul *Pardo, to change his name to its English equivalent, Brown. Jews identified easily with the larger community into which they were integrated.

In 1711 the most prominent Jewish businessmen of New York City, including the hazzan (ḥazzan), made contributions to help build Trinity Church. In the days before the Revolution the Union Society, a charity composed of Jews, Catholics, and Protestants, made provision for the poor of Savannah, Georgia.

The typical American Jews of the mid-18th century was of German origin, a shopkeeper, hardworking, enterprising, religiously observant, frequently uncouth and untutored, but with sufficient learning to keep his books and to write a simple business letter in English. What had he accomplished by 1776? He had brought with him from Europe to America a sense of Jewish communalism and despite his absorption in business as he struggled for economic sufficiency he kept his congregation alive. He tended to be careless in matters of ritual, governed as he was by the unconscious principle of salutary neglect and a readiness to make concessions in order to keep more negligent fellow-Jews within the ambit of the minyan [[10 or more Jews needed for a worship service]]. He seems not to have felt that he was in galut [[exile]]. America was home for him.

[[The natives were not asked and were not listed as human beings. The aim of the white colonialists was the occupation of the whole continent for trade with India]].

Early National Period, 1776-1820.

[[The revolution of 1776 and the founding of the racist "USA" against the old racist colonial power of England was the model for independence of the states in Central and South America against racist Spain and Portugal. This lasting impetus of revolution against the old racist colonial powers was also provoking the fall of the arrogant French court and at the end brought Napoleon to power]].

[Jews in the white racist struggle for independence from England]

[[The natives to whom the soil belonged were never asked]].

When the Revolution broke out in 1775, most Jews were Whigs. They had few ties to England and were determined to become first-class (col. 1590)

citizens. Many of them had accepted the revolutionary propaganda that had already been aired for half a generation. They were fascinated by the "Great Promise" of July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence. Quite a number were in the militia - which was compulsory - and some served in the Continental line as soldiers and officers. Three officers attained relatively high rank. Jewish merchants ventured into privateering and blockade-running, but the Jew on "Front Street" was still a shopkeeper somehow or other finding the consumer goods so desperately needed in a nonindustrial country whose ports were often blockaded by the British fleet.

The most notable Jewish rebel was the Polish immigrant, Haym *Salomon, an ardent patriot who served as an underground agent for the American forces while working for the British. When discovered, he fled to Philadelphia where he soon became the best known bill broker in the country. It was in his capacity as a chief bill broker to Robert Morris, the superintendent of finance, that Solomon helped make funds available for the successful expedition against Cornwallis which brought the war to an end.

[Emancipation and restrictions since 1776 - new community life by Sephardi Jews - Jewish institutions]

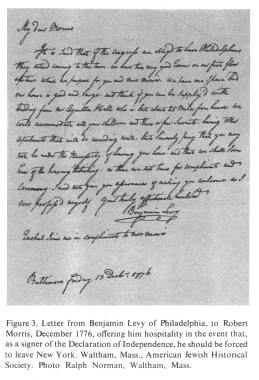

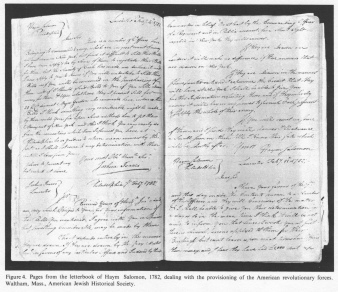

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): "USA", vol. 15, col. 1591-1592: Pages from the letterbook of

Haym Salomon, 1782, dealing with the provisioning of the American revolutionary forces.

Waltham, Mass., American Jewish Historical Society.

Independence from England did not at once materially improve the political status of the American Jew. In 1787 the Northwest Ordinance guaranteed that the Jew would be on the same footing as his fellow citizens in all new states: the Constitution adopted a year later gave him equality on the federal level. At the time this was not a great victory, for most rights were still resident in the states, and as late as 1820 only seven of the 13 original states had recognized the Jew in a political sense. Ultimately men of talent were (col. 1591)

appointed or elected town councilors, judges of the lower courts, and members of the state legislature. The national authorities appointed them marshals and consuls; outstanding individuals made careers for themselves in the army and the navy, though the latter branch of the service was particularly inhospitable to Jewish aspirants.

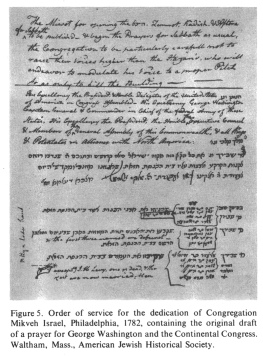

the Newport Jewish community had died after 1800, but the other "Sephardi" congregations continued to prosper, reinforced by a new "western" community created in *Richmond. The apparatus of all these synagogues was modified and enlarged: the status of the hazzan (ḥazzan) [[cantor]] was raised to that of the Christian minister; secretaries and committees were common, and eleemosynary societies and confraternities (hevrot (ḥevrot)) rose in every congregation during this post-Revolutionary period.

From then on special organizations took care of the poor, the sick, and the dead. Some of these societies, primarily concerned with mutual aid, offered sick and death benefits. Originally these new groups - whether composed of men or women - were closely affiliated with congregations, but from the very beginning they enjoyed a degree of autonomy. Ultimately the charities would emancipate themselves from congregational control.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): "USA", vol. 15, col. 1593-1594. Map 1. Main centers of

Jewish population in the U.S., 1800, according to the state borders of today.

[Professions: money trade and big trade, law, medicine, engineering, education, journalism]

Changes also occurred in the economic activities of the Jews. As cotton became "king", Jewish planters increased; merchant shippers, though still rich and powerful, lost their relative importance as the retail and wholesale urban merchants turned away from the sea and became specialists. With good titles possible, land speculation within the ambit of states and territories assumed increasing importance;

[[The natives were driven away and were not asked. The treaties between the whites and the natives were nothing worth because for the white government it was always clear that the whole continent would be white at the end with the aim for a good Indian trade]].

Cohen & Isaacs of Richmond (col. 1592)

employed Daniel Boone to survey their holdings in Kentucky. Independence and affluence brought new economic fields into prominence in the United States. Jews began turning to banking and moneylending, insurance, industry, and the stock exchange.

By 1820 they had entered the professions of law, medicine, engineering, education, and journalism. Many Jews in the post-Revolutionary period, especially in South Carolina, were men of education and culture, at home in the classics, in modern languages and literatures, devotees of music and poetry. A number of literati both in the North and in the South were playwrights of some distinction; all were ardent cultural nationalists.

[[The natives were never listed in any stock exchange. So, for the white racists and for the Jews the natives never existed. Add to this the bankers were responsible to finance the wars and the army and became more and more important]].

[Judeophobia]

Patriotism, however, was no guarantee against Judeophobia which increased as the Jew rose in wealth, prominence, and visibility. Those who entered politics and joined the Jeffersonians were vilified in the Federalist press as "democrats", a derogatory epithet. Jews seeking public office, even Christians of Jewish descent, were frequently and viciously attacked.

[Jewish literature]

Aside from a few plays, miscellaneous orations, addresses, and literary anthology, Jews wrote little. Jewish publishers in New York made their contribution by reprinting good books. In the area of Jewish culture, American Jewry was equally uncreative. In the 1760s two English translations of Hebrew prayer books had appeared; after the Revolution, Jews brought out a few sermons and eulogies, a Hebrew grammar, and by 1820 a rather good polemic entitled Israel Vindicated, though there is no absolute proof that this was written by a Jews. More important was the reprinting of a number of apologetic works directed against deists and Christian missionaries. Some of these books had originally appeared in England.

[Acculturated Jews in every white town in the criminal racist "USA"]

The typical American Jew of the post-Revolutionary period was native born and completely acculturated. Intermarriage was not uncommon. Nominally he was a follower of tradition; actually he was often indifferent to the practices of his faith. Basically he was loyal to his group, strongly and even belligerently attached to American and (col. 1595)

world Jewry by a strong sense of Kinship. Altogether there were about 4,000 Jews in the United States by 1820, most of them in the cis-Allegheny regions, but there was no town in the United States, even distant *St. Louis, which did not shelter some Jews. Many of them were recent German immigrants who had drifted in after the Napoleonic wars. By the turn of the 18th century Central Europeans had already started a little Ashkenazi synagogue in Philadelphia. Within a generation Ashkenazi culture dominated the American Jewish scene [[by white Jewish banking money]].

[J.R.M.]> (col. 1596)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|