Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Bavaria

Settlements - Crusade attacks - expulsions - resettlements and new expulsions - Napoleonic rights and riots as reactions - equality and anti-Semitism as reaction - Holocaust

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 347-348, map of Bavaria showing Jewish population centers from the tenth century to 1932-33

from: Bavaria; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971), vol. 4

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<BAVARIA, Land in S. Germany, including Franconia.

[Jewish settlement on commercial routes to Hungary and Russia - attacks during First and Second Crusade - persecutions and destruction of Jewish communities - total expulsion until 1551]

Jews are first mentioned there in the *Passau toll regulations of 906. Their settlement was apparently connected with the trade routes to Hungary, southern Russia and northeastern Germany. A Jewish resident of Regensburg is mentioned at the end of the tenth century. (col. 343)

Regensburg was a center of Jewish scholarship from the 12th century. Regensburg was the cradle of the medieval Ashkenazi *Hasidism (Ḥasidism) and in the 12th and 13th centuries the main center of this school. The traveler *Pethahiah b. Jacob set out from there in about 1170. Prominent scholars of Bavaria include

-- *Meir b. Baruch of Rothenburg (the leading authority of Ashkenazi Jewry, 13th century)

-- Jacob *Weil (taught at Nuremberg and Augsburg, beginning of the 15th century)

-- Moses *Mintz (rabbi of Bamberg, 1469-1474)

-- and the Renaissance grammarian Elijah *Levita (a native of Neustadt). (col. 346)

The communities which had been established in *Bamberg and Regensburg were attacked during the First Crusade in 1096, and those in *Aschaffenburg, *Wuerzburg, and *Nuremberg during the (col. 343)

Second Crusade in 1146-47. Other communities existed in the 13th century at Landshut, Passau, *Munich, and *Fuerth. The Jews in Bavaria mainly engaged in trade, dealing in slaves, gold, silver and other metals, and in moneylending.

In 1276 they were expelled from Upper Bavaria and 180 Jews were burned at the stake in Munich following a *blood libel in 1285. The communities in Franconia were attacked during the *Rindfleisch persecutions in 1298. The *Armleder massacres, charges of desecrating the *Host at *Deggendorf, Straubing, and Landshut, and the persecutions following the *Black Death (1348-49), brought catastrophe to the whole of Bavarian Jewry. Many communities were entirely destroyed, among them *Ansbach, Aschaffenburg, *Augsburg, Bamberg, *Ulm, Munich, Nuremberg, Passau, Regensburg, *Rothenburg, and Wuerzburg.

[[The stupid and criminal Church is never mentioned as the main cause for the persecutions]].

Those who had fled were permitted to return after a time under King Wenceslaus. (col. 344)

In 1442 the Jews were again expelled from Upper Bavaria. Shortly afterward, in 1450, the Jews in Lower Bavaria were flung into prison until they paid the duke a ransom of 32,000 crowns and were then driven from the duchy. As a result of agitation by the Franciscan John of *Capistrano, they were expelled from Franconia.

In 1478 they were expelled from Passau, in 1499 from Nuremberg, and in 1519 from Regensburg. The few subsequently remaining in the duchy of Bavaria were expelled in 1551.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 344, the main synagogue in Fuerth, Bavaria,

built in 1616. An engraving made in 1839. Fuerth Municipality. Photo Knut Mayer

[Resettlement since 17th century - expulsion of Jews with Austrian origin - Court Jews]

Subsequently, Jewish settlement in Bavaria ceased until toward the end of the 17th century, when a small community was founded in *Sulzbach by refugees from *Vienna. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14) several Jews from Austria serving as purveyors to the army or as moneylenders settled in Bavaria. In this period a flourishing community grew up in Fuerth, whose economic activities helped to bring prosperity to the city.

After the war the Jews of Austrian origin were expelled from Bavaria, but some were able to acquire the right to reside in Munich as monopoly holders, *Court Jews, mintmasters, and physicians. Several Court Jews belonging to the *Frankel and *Model families became prominent in Ansbach and Fuerth for a while in the 18th century, particularly because of their services in managing the state's economy.

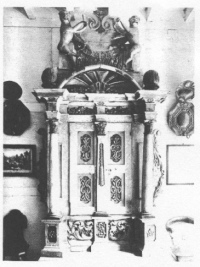

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 344, Ark of the Law from the synagogue in Westheim, Bavaria, c. 1725.

The ark was latterly in the Wuerzburg Museum, which was destroyed in World War II. Photo Gundermann, Wuerzburg

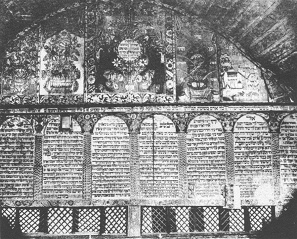

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 346, wall paintings in the synagogue of Bechhofen by Eliezer Sussmann, 1733.

The Synagogue was restored in 1914 by the Bavarian Commission for National Art Treasures

and was destroyed by the Nazis. Jerusalem, Israel Museum Archives.

[Napoleonic laws - restriction after Napoleon since 1815 - riots and emigration movements - Jewish rights since 1861 - equality since 1872 by Reich law - economic activities]

In the Napoleonic era Jewish children were permitted to attend the general schools (1804), the men were accepted into the militia (1805), the poll tax was abolished (1808), and Jews were granted the status of citizens (1813). However, at the same time their number and rights of residence were still restricted, and only the eldest son in a family was allowed to marry (see *Familiants Laws). In 1819 anti-Jewish disorders broke out in Franconia (the "*Hep! Hep!" riots). Owing to the continued adverse conditions and the restrictions on families a large number of young Bavarian Jews emigrated to the [[racist]] United States. A second wave of emigrants left for the U.S. in the reaction following the 1848 Revolution.

In 1861 the discriminatory restrictions concerning Jews were abolished, and Jews were permitted to engage in all occupations. However, complete equality was not granted until 1872 by the provisions of the constitution of the German Reich of 1871.

Certain special "Jewish taxes" were abolished only in 1880. The chief occupation of Bavarian Jews in the 19th century was the livestock trade, largely in Jewish hands (see *Agriculture). By the beginning of the 20th century Jews had considerable holdings in department stores and in a few branches of industry.

A number of Jews were active after World War I in the revolutionary government of Bavaria which was headed by a Jew, Kurt *Eisner, who was prime minister before his assassination in 1919. [[Bavaria should not be a Communist state, so he was murdered]].

[1919-1933: anti-Semitic parties - partly expulsion in 1923 - cultural life - Jews at universities]

In the reaction which followed World War I [[in the reaction to the German defeat and the loss of the Emperor system, and in the reaction to the Treaty of Versailles which was followed by further foreign partition manipulations between Bavaria and Prussia]] there was a new wave of anti-Semitism, and in 1923 most of the East European Jews resident in Bavaria were expelled. This was the time when the National Socialist Movement made its appearance in the region [[headed against the Communist party which had whole towns in their hands]], and anti-Semitic agitation increased [[because some Communist leaders were Jews, and also the Russian Communist government was mostly consisting of Jews]].

Jewish ritual slaughter was prohibited in Bavaria in 1931.

The size of the Jewish population in Bavaria varied relatively little from the Napoleonic era to 1933, numbering 53,208 in 1818 and 41,939 in 1933. A Bavarian Jewish organization, the Verband bayerischer israelitischer Gemeinden [[Confederation of Bavarian Jewish Communities]], was set up in 1921 and included 273 communities and 21 rabbinical institutions. In 1933 the largest and most important communities in Bavaria were in Munich (which had a Jewish population of 9,000), Nuremberg (7,500), Wuerzburg (2,150), Augsburg (1,100), (col. 345)

Fuerth (2,000), and Regensburg (450). At this time the majority of Bavarian Jews were engaged in trade and transport (54.5%) and in industry (19%), but some also in agriculture (2.7% in 1925 compared with 9.7% in 1882). Over 1,000 Jews studied at the University of Bavaria after World War I, a proportion ten times higher than that of the Jews to the general population.

[[...]]

In the 19th / 20th centuries there lived in Munich the folklorist and philologist Max M. *Gruenbaum; Raphael Nathan Neta *Rabinovitz, author of Dikdukei Soferim; and Joseph *Perles, rabbi of Augsburg, 1875-1910.

[Holocaust period 1933-1945: center Munich - cc Dachau]

The Jews in Bavaria were among the first victims of the Nazi movement, which spread from Munich and Nuremberg. Virulent and widespread anti-Semitic agitation caused the depopulation of scores of the village communities so characteristic of Bavaria, especially after the *Kristallnacht in 1938, which was particularly destructive in Bavaria, a hotbed of Nazism and home of many Nazis.

[[Hitler was a manipulated Austrian child, a criminal foreigner which could have been expelled easily, but there was no action by the coward Prussian police. The center of Hitler's National Socialist party was *Munich. This party was consequent against Communism and against the criminal international financial stock exchange system. The party organized work for the people and was financed by many important persons from abroad in the hope to destroy Communism and for a "Big Germany". Many Germans did not have any idea that Hitler was financed by foreigners but only thought in the dimension having work or not. But already the contradiction of the hair colour - Aryans had blond hair, Hitler had black hair - was one of the faults of the system, and the German population had to be mute...]]

The first concentration camp was established at *Dachau in Bavaria and many Jews from Germany and other countries in Europe perished there.

[[The deportations and other camps are not mentioned in the article]].

[1945-1970: DP camps in Bavaria - Jewish survivors by mixed marriages - neo-Nazis in the 1960s - Auerbach affair - numbers 1969]

After World War II thousands of Jews were assembled in displaced persons' camps in Bavaria; the last one to be closed down was in Foehrenwald. Almost all of the 1,000 Bavarian Jews who survived the Holocaust were saved because they were married to Germans or where born of mixed marriages. A year after the end of hostilities a Nazi underground movement remained active in Bavaria, and the neo-Nazi anti-Jewish demonstrations of June 1965 started in Bamberg. Anti-Semitic sentiment was also aroused when the minister of Jewish affairs, Philip Auerbach, was prosecuted for misappropriation of funds in 1951. (col. 346)

[[Auerbach, a Jew, had misused funds given by Germans for the Jewish survivors]].

In 1969 there were in Bavaria about 4,700 Jews, forming 13 communities, the majority from the camps of Eastern Europe. The largest communities were in Munich (3,486), Nuremberg (275), Wuerzburg (141), Fuerth (200), Augsberg (230), and Regensburg (150). There were smaller numbers of Jews in *Amberg, Bamberg, *Bayreuth, Straubing, and Weiden.

See also *Germany.

Bibliography

-- S. Taussig: Geschichte der Juden in Bayern [[History of the Jews in Bavaria]] (1874)

-- Germ Jud, 1 (1963), 22-24; 2 (1968), 57-60

-- S. Schwarz: Juden in Bayern im Wandel der Zeiten [[Jews in Bavaria during the changing of the times]] (1963)

-- R. Strauss: Regensburg and Augsburg (1939)

-- H.B. Ehrmann: Struggle for Civil and Religious Emancipation in Bavaria in the First Half of the 19th Century (1948), 199

H.C. Vedeler, in: Journal of Modern History, 10 (1938), 473-95

-- P. Wiener-Odenheimer: Die Berufe der Juden in Bayern [[Jewish jobs in Bavaria]] (1918), 131

-- H. Schnee: Die Hoffinanz und der moderne Staat [[Court finance and the modern state]], 4 (1963), 187 ff.

[Z.AV. / ED.]> (col. 347)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter |

| Sources |

||

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 343-344 |

.  Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 345-346 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Bavaria, vol. 4, col. 347-348 |

Č Ḥ ¦ Ṭ Ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

^