Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Berlin 01: Middle Ages and regulations of electorate Brandenburg

Old communities - Black Death - persecutions and expulsions - regulations and rich families - tax terror and restrictions - equality and development - influx of Polish Jews since 1772

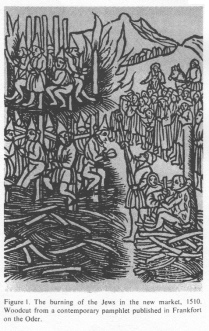

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Berlin, vol. 4, col. 642. The burning of the Jews (with Jewish pointed huts) in the

new market, 1510. Woodcut from a contemporary pamphlet published in Frankfort on the Oder.

from: Berlin; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971), vol. 4

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<BERLIN, largest city in Germany. The capital of Germany until 1945, it is now divided into West Berlin and East Berlin [[and was re-united in 1989 and is capital again]].

The Old Community (1295-1573).

Jews are first mentioned in a letter from the Berlin local council of Oct. 28, 1295, forbidding wool merchants to supply Jews with wool yarn. Suzerainty over the Jews belonged to the margrave who from 1317 pledged them to the municipality on varying terms, but received them back in 1363. Their taxes, however, were levied by the municipality in the name of the ruler of the state.

The oldest place of Jewish settlement in "Great Jews' Court" (Grosser Judenhof) and "Jews' Street"had some of the characteristics of a Jewish quarter, but a number of wealthier Jews lived outside these areas. Until 1543, when a cemetery was established in Berlin, the Jews buried their dead in the town of Spandau.

The Berlin Jews engaged mainly in commerce, handicrafts (insofar as this did not infringe on the privileges of the craft guilds), money changing, money lending, and other pursuits. Few attained affluence. They paid taxes for the right to slaughter animals ritually, to sell meat, to marry, to circumcise their sons, to buy wine, to receive additional Jews as residents of their community, and to bury their dead.

[Black Death in Berlin 1349-50: riots, houses burnt, Jews killed and expelled]

During the *Black Death (1349-50), the houses of the Jews were burned down and the Jewish inhabitants were killed or expelled from the town.

From 1354, Jews again settled in Berlin.

In 1446 they (col. 639)

were arrested with the rest of the Jews in *Brandenburg, and expelled from the electorate [[Germ.: Fuerstentum]] after their property had been confiscated. A year later Jews again began to return, and between 1454 and 1475 there were 23 recorded instances of Jews establishing residence in Berlin in the oldest register of inhabitants.

A few wealthy Jews were admitted into Brandenburg in 1509.

[1510: 38 innocent Jews at stake - 1539: proof of innocence]

In 1510 the Jews were accused of desecrating the *Host and stealing sacred vessels from a church in a village near Berlin. 111 Jews were arrested and subjected to examination, and 51 were sentenced to death; of these 38 were burned at the stake in the new market square together with the real culprit, a Christian, on July 10, 1510. Subsequently, the Jews were expelled from the entire electorate of Brandenburg. All the accused were proved completely innocent at the Diet of Frankfort in 1539 through the efforts of *Joseph (Joselmann) b. Gershom of Rosheim and Philipp *Melanchthon.

[Jews admitted in 1543 - Jews expelled again in 1571]

The elector [[Germ.: Kurfuerst]] Joachim II (1535-71) permitted the Jews to return and settle in the towns in Brandenburg, and Jews were permitted to reside in Berlin in 1543 despite the opposition of the townspeople. In 1571, when the Jews were again expelled from Brandenburg, the Jews of Berlin were expelled "for ever". For the next 100 years, a few individual Jews appeared there at widely scattered intervals. About 1663, the Court Jew Israel Aaron, who was supplier to the army and the electoral court, was permitted to settle in Berlin.

Beginnings of the Modern Community (to 1812).

[Rich Jewish families from Vienna in 1670 - privileges in 1671 - growing Jewish community - protection letters issued by the authorities - more Jews coming to Brandenburg - tensions with the rich Jewish families - the government's regulations]

After the expulsion of the Jews from *Vienna in 1670, the elector issued an edict on May 21, 1671, admitting 50 wealthy Jewish families from Austria into the mark of Brandenburg and the duchy of Crossen (Krosno) for 20 years. They paid a variety of taxes for the protection afforded them but were not permitted to erect a synagogue.

The first writ of privileges was issued to Abraham Riess (Abraham b. Model Segal) and Benedict Veit (Baruch b. Menahem Rositz), on Sept. 10, 1671, the date considered to mark the foundation of the new Berlin community. Notwithstanding the opposition of the Christians (and also of Israel Aaron who feared competition) to any increase in the number of Jewish residents in Berlin, the community grew rapidly, and in the course of time the authorities granted letters of protection to a considerable number of Jews. In addition, many unvergleitete Jews (i.e., without residence permits) infiltrated into Brandenburg.

The first population census of 1700 showed that there were living in Berlin at that time 70 Jewish vergleitete families with residence permits, 47 families without writs of protection, and a few peddlers and beggars (about 1,000 persons). The refugees from Austria now became a minority, and quarrels and clashes broke out within the community (see below).

The Jews of Berlin engaged mainly in commerce. The guilds and merchants were bitterly opposed to them and they were accused of dealing in stolen goods. The Christians demanded the expulsion of the foreign Jews or restriction of their economic activity to dealing in secondhand goods and pawnbroking [[money lending on the base of deposition of goods]], not to be conducted in open shops. The government responded only partly to such demands, being interested in the income from the Berlin Jews. It imposed restrictions upon the increase of the Jewish population in the city and issued decrees increasing their taxes, making the community collectively responsible for the payment of protection money (1700), for prohibiting Jews from maintaining open shops, from dealing in stolen goods (1684), and from engaging in retail trade in certain commodities except at fairs (1690).

Nevertheless, the number of Jewish stores grew to such an extent that there was at least one in every street. The Jews were subsequently ordered to close down every store opened after 1690, and all other Jews were forbidden to engage in anything but dealing in old clothes (col. 640)

and pawnbroking. They could be exempted from these restrictions on payment of 5,000 thalers.

[Tax terror since 1701 against the Jews under Frederick III]

Elector Frederick III, who became Kind Frederick I of Prussia in 1701, began a systematic exploitation of the Jews by means of various taxes. The protection tax was doubled in 1688; a tax was levied for the mobilization and arming of an infantry regiment; 10,000 ducats were exacted for various misdemeanors [[little criminalities]]; 1,100 ducats for children recognized as vergleitete; [[without residence permits]]; 100 thalers annually toward the royal reception in Berlin; 200-300 thalers annually in birth and marriage taxes; and other irregular imposts.

[New restrictions and rights for the Jews under Frederick William I]

Frederick William I (1713-40) limited (in a charter granted to the Jews on May 20, 1714) the number of tolerated Jews to 120 householders, but permitted in certain cases the extension of letters of protection to include the second and third child. The Jews of Berlin were permitted to engage in commerce almost without restriction, and in handicrafts provided that the rights of the guilds were not thereby infringed [[reduced]]. By a charter granted in 1730, the number of tolerated Jews was reduced to 100 householders. Only the two oldest sons of the family were allowed to reside in Berlin - the first, if he possessed 1,000 thalers in ready money, on payment of 50 thalers, and the second if he owned and paid double these amounts.

Vergleitete Jews might own stores, but were forbidden to trade in drugs and spices (except for tobacco and dyes [[colors]]), in raw skins, and in imported woolen and fiber goods [[fabric]], and were forbidden to operate breweries or distilleries. They were also forbidden to engage in any craft, apart from seal engraving, gold and silver embroidery, and Jewish ritual slaughter. Land ownership by Jews had been prohibited in 1697 and required a special license which could be obtained only with great difficulty. Jews might bequeath their property to their children, but not to other relatives. On Jan. 22, 1737, Jews were forbidden to buy houses in Berlin or to acquire them in any other fashion.

In 1755 an equal interest rate was fixed for Jews and Christians.

[Rich Jewish families - money trade in Jewish hands - again restrictions - and some new rights - Itzig family with full civic rights in 1791 - and new restrictions]

The Jews in Berlin in the 18th century primarily engaged as commercial bankers and traders in precious metals and stones. Some served as *court Jews. Members of the *Gomperz family were among the wealthiest in Berlin.

In the course of time, all trade in money in Berlin was concentrated in Jewish hands. One of the pioneers of Prussian industry was Levi IIf, who established a ribbon factory in Charlottenburg in 1718. At the same time the royal policy continued of restricting the Jewish population of Berlin, and even decreasing it as far as possible. When in 1737 it became evident that the number of Jewish families in Berlin had risen to 234, a decree was issued limiting the quota to 120 families (953 persons) with an additional 48 families of "communal officers" (243 persons). The remainder (584) were ordered to leave, and 387 did in fact leave. However in 1743 Berlin had a Jewish population of 333 families (1,945 persons).

*Frederick the Great (1740-86) denied residence rights in Berlin to second and third children of Jewish families and wished to limit the total number of protected Jews to 150. However, the revised Generalprivilegium [[General Privilege]] and the royal edict of April 17, 1750, which remained in force until 1812, granted residence rights to 203 "ordinary" families, whose eldest children could inherit that right, and to 63 "extraordinary" families, who might possess it only for the duration of their own lifetime. A specified number of "public servants" was also to be tolerated. However, during his reign, the economic, cultural, and social position of the Jews in Berlin improved. During the Seven Years' War, many Jews became wealthy as purveyors to the army and the mint and the rights enjoyed by the Christian banker were granted to a number of Jews.

In 1763, the Jews in Berlin were granted permission to acquire 70 houses in (col. 641)

place of 40. While their role in the retail trade decreased in importance because of the many restrictions imposed, the number of Jewish manufacturers, bankers, and brokers increased. On May 2, 1791, the entire *Itzig family received full civic rights, becoming the first German Jews to whom they were granted. At the same time, the king compelled the Jews to supply a specified quantity of silver annually to the mint at a price below the current one (1763), to pay large sums for new writs of protection (1764), and, in return for various privileges and licenses, to purchase porcelain ware to the value of 300-500 thalers from the royal porcelain factory and sell it abroad.

[[The criminal anti-Semitic church as the main force of anti-Semitism is never mentioned in this article]].

[Reforms in the Jewish community - Enlightenment movement and assimilation movement - but no equality - and discussions about the "Jewish question" - equality under Napoleon in 1812]

As a concomitant [[side effect]] of economic prosperity, there appeared the first signs of cultural adaptation. Under the influence of Moses *Mendelssohn, several reforms were introduced in the Berlin community, especially in the sphere of education. In 1778 a school, *Juedische Freischule [[Jewish Free School]] (Hinnukh Ne'arim (Ḥinnukh Ne'arim)), was founded, which was conducted along modern comprehensive principles and methods. Mendelssohn and David *Friedlaender composed the first German reader for children. The dissemination of general (non-Jewish) knowledge was also one of the aims of the Hevrat (Ḥevrat) Doreshei Leshon Ever ("Association of Friends of the Hebrew Language"), founded in 1783, whose organ Ha-Me'assef (see *Me'assefim) began to appear in Berlin in 1788.

Mendelssohn's home became a gathering place for scholars, and Berlin became the fount of the Enlightenment movement (*Haskalah) and of the trend toward *assimilation. The salons of Henrietta *Herz, Rachel *Varnhagen, and Dorothea *Schlegel served as rendezvous for both Jews and Christians of the social elite of Berlin. However, progress toward legally recognized civil equality was slow.

After the new Exchange building was erected in Berlin in 1805, a joint "corporation" of Christians and Jews was (col. 642)

established in which the latter were in the majority and had equal rights. IN 1803-04, during the literary controversy over the Jewish question, the government took no action whatever on behalf of the Jews, but after the Prussian defeat by Napoleon the Municipal Act of Nov. 19, 1809, facilitated their attainment of citizen status. Solomon *Veit was elected to the Berlin municipal council and David Friedlaender was appointed a city councilor. The edict of March 11, 1812, finally bestowed Prussian citizenship upon the Jews; all restrictions on their residence rights in the state, as well as the special taxes they had to pay, were now abolished.

Internal Life (17th-18th Centuries).

[Government-approved regulations for the Jewish community since 1700 - communal leaders misuse the authority - fine of 6,500 thalers in 1717 - new statutes in 1722 and 1723 - rabbis]

The fierce controversies that had broken out in the Jewish community during the communal elections in 1689 resulted in governmental intervention in the administrative affairs of the community. Thus the decree of January 24 and the statute of Dec. 7, 1700, included government-approved regulations for the Jewish community. The communal leaders (parnasim), elected for three years, were empowered to impose fines (two-thirds of which went to the state treasury and one-third to the communal charity fund) and to excommunicate members with the consent of the local rabbi and government.

The "chief parnas" acted as mediator between the Jews and the state. In 1717, complete anarchy in the conduct of communal affairs became evident; the parnasim were deposed and a fine was imposed on the community amounting to 10,000 thalers, later reduced to 6,500.

In 1722 and in 1723 new statutes were promulgated regulating the organizational structure of the community. A part from the chief parnasim, who were appointed by the king and functioned under the supervision of a Jewish commission, a communal committee of three, four, or five parnasim was set up which would coopt to itself two optimates (tovim) and two alternates (ikkurim) for handling particularly important matters.

To decide on matters of extreme importance larger committees were appointed of 15, 18 or 32 members. In 1792 a supervisory committee was created consisting of three members to supervise the fiscal aspect of communal administration.

The first rabbi, elected at the time of the erection of the Berlin synagogue in the Heiderentergassse, was Michael Hasid (Ḥasid) (officiated 1714-28). His successors include Jacob Joshua b. Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch *Falk of Cracow (1731-34), author of Penei Yehoshu'a, David *Fraenkel (1743-62), author of Korban ha-Edah on the Palestinian Talmud and teacher of Moses Mendelssohn, and Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch b. Aryeh Loeb (Hirschel *Levin, 1772-1800), known for his opposition to Haskalah.> (col. 643)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter |

| Sources |

||

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Berlin, vol. 4, col. 639-640 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Berlin, vol. 4, col. 641-642 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Berlin, vol. 4, col. 643 |

Č Ḥ ¦ Ṭ Ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

^