Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Frankfort on the Main 02: Enlightenment - Napoleon - emancipation

Fire of 1711 - Enlightenment and reform discussions - Napoleon and reaction after his death with Hep-Hep 1819 - reforms, emancipation and split of the community - institutions and cultural life

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<18th Century.

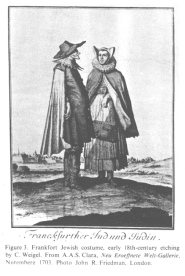

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on the Main, vol. 7, col. 86, Frankfort Jewish costume "Franckfurther Jud und Jüdin" ("Frankfort Jew and Jewess"), early 18th-century etching by C. Weigel. From A.A.S. Clara: "Neu Eroeffnete Welt-Gallerie", Nuremberg 1703. Photo John R. Friedman, London [[It's clear that the costume looks ridiculous and this was wanted by the "Christian" rulers, a hat like a farmer for the Jews, and a hat like a donkey for the Jewess. This was wanted by the "Christian" with the authorization of the criminal anti-Jewish church]].

[Fire in 1711 - Enlightenment - inner quarrels within the Jewish community against the dominating families - schooling and education reform - blocked reforms by the chief rabbi]

In 1711 almost the entire Jewish quarter was destroyed by a fire which broke out in the house of the chief rabbi, *Naphtali b. Isaac ha-Kohen. The inhabitants found refuge in gentile homes, but had to return to the ghetto after it had been rebuilt.

J.J. *Schudt gave a detailed account of Jewish life at Frankfort in this period. The penetration of Enlightenment found the community in a state of unrest and social strife. Communal life had long been dominated by a few ancient patrician families, some of whom were known by signs hanging outside their houses, like the *Rothschild ("Red Shield"), Schwarzschild, *Kann, and *Schiff families. The impoverished majority challenged the traditional privileges of the wealthy oligarchy, and the city council repeatedly acted as arbitrator between the rival parties.

Controversies on religious and personal matters such as the *Eybeschuetz-*Emden dispute further weakened unity in the community. Nevertheless, there was no decline in intellectual activity, and the yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]]of Samuel Schotten and Jacob Joshua b. Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch *Falk attracted many students.

The movement for the reformation of Jewish education fostered by the circle of Moses *Mendelssohn in Berlin found many sympathizers in Frankfort, especially among the well-to-do class who welcomed it as a step toward *emancipation. Forty-nine prominent members of the community subscribed for Mendelssohn's German translation of the Bible (1782), but the chief rabbi, Phinehas *Horowitz, attacked the book from the pulpit. When in 1797 a project was advocated for a school with an extensive program of secular studies, Horowitz pronounced a ban on it. He was supported by most of the communal leaders, though many had their children taught non-Jewish subjects privately. The ban had to be withdrawn by order of the magistrate. Some years previously, Horowitz had acted similarly against the kabbalist Nathan *Adler.

[French Revolution: Bombardment opening the "Jewish street" ghetto]

Meanwhile the French revolutionary wars had made their fist liberating impact on Frankfort Jewry. In 1796 a bombardment destroyed the greater part of the ghetto, and in 1798 the prohibition on leaving the ghetto on Sundays and holidays was abolished.

19th and 20th Centuries.

["Jewish street" ghetto abolished in 1811 - Jewish tax - Hep-Hep riots in 1819 - discriminatory laws again since 1824]

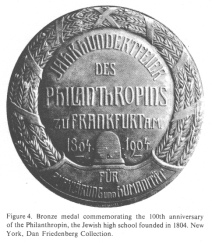

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on the Main, vol. 7, col. 88, bronze medal commemorating the 100th anniversary

of the Philanthropin, the Jewish high school founded in 1804. New York, Dan Friedenberg Collection.

The incorporation of Frankfort in Napoleon's Confederation of the Rhine (1806) and the constitution of the grand duchy of Frankfort (1810) gradually changed the status of the Frankfort Jews, bringing them nearer emancipation. In 1811 the ghetto was finally abolished, and a declaration of equal rights for all citizens expressly included the Jews, a capital payment of 440,000 florins having been made by the community.

However, the reaction following Napoleon's downfall brought bitter disappointment. The senate of the newly constituted Free City tried to abolish Jewish emancipation and thwarted the efforts made by a community delegation to the Congress of *Vienna. After prolonged negotiations, marked by the *"Hep-Hep" anti-Jewish disorders in 1819, the senate finally promulgated an enactment granting equality to the Jews in all civil matters, although reinstating many of the old discriminatory laws (1824). The composition and activities of the community board remained subject to supervision and confirmation by the senate.

[Inner reform movement]

Meanwhile the religious rift in the community had widened considerably. Phinehas Horowitz's son and successor, Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch *Horowitz, was powerless in face of the increasing pressure for social and educational reforms. He did in fact renew his father's approbation of Benjamin Wolf *Heidenheim's edition of the prayer book which included a German translation and a learned commentary. However, this first stirring of *Wissenschaft des Judentums [[Science of Jewry]] could not satisfy those in the community desiring reform and assimilation. In 1804 they founded a school, the Philanthropin [[The Philanthropic]], with a markedly secular and assimilationist program. This institution became a major center for reform in Judaism. From (col. 87)

1807 it organized reformed Jewish services for the pupils and their parents. In the same year a Jewish lodge of *Freemasons was established, whose members actively furthered the causes of reform and secularization in the community. From 1817 to 1832 the board of the community was exclusively composed of members of the lodge. In 1819 the Orthodox heder (ḥeder) institutions [[Jewish religious school to age of 13]] were closed by the police, and the board prevented the establishment of a school for both religious and general studies.

Attendance at the yeshivah [[religious Torah school]], which in 1793 still had 60 students, dwindled: In 1842 the number of Orthodox families was estimated to account for less than 10% of the community. In that year, a Reform Association demanded the abolition of all "talmudic" laws, circumcision, and the messianic faith. The aged rabbi, Solomon Abraham Trier, who had been one of the two delegates from Frankfort to the Paris *Sanhedrin in 1807, published a collection of responsa from contemporary rabbis and scholars in German on the fundamental significance of circumcision in Judaism (1844).

A year later a conference of rabbis sympathizing with reform was held in Frankfort. A leading member of this group was Abraham *Geiger,a native of Frankfort, and communal rabbi from 1863 to 1870.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on the Main, vol. 7, col. 89, drawing of the synagogue on the Boernestrasse,

[[Boerne Street]], built in 1855-60 and burned down in 1938. Courtesy Frankfort Historical Museum

[Emancipation since 1864 - Orthodox split in 1864 and 1876 - new Orthodox synagogue - leading Orthodox community]

The revolutionary movement of 1848 hastened the emancipation of the Frankfort Jews, which was finally achieved in 1864.

The autocratic regime of the community board weakened considerably. A small group of Orthodox members then seized the opportunity to form a religious association within the community, the "Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft" [[Israelite Religion Community]], and elected Samson Raphael *Hirsch as their rabbi in 1851.

The Rothschild family made a large donation toward the erection of a new Orthodox synagogue.

When the community board persisted in turning a deaf ear to the demands of the Orthodox minority, the association seceded from the community and set up a separate congregation (1876). After some Orthodox members, supported by the Wuerzburg rabbi, Seligmann Baer *Bamberger, had refused to take this course, the community board made certain concessions, enabling them to remain within the community. A communal Orthodox rabbi, Marcus *Horovitz, was installed and a new Orthodox synagogue was erected with communal funds. From then on the Frankfort Orthodox community, its pattern of life and educational institutions, became the paradigm of German *Orthodoxy.

[Numbers - institutions - Frankfurter Zeitung by Leopold Sonnemann - institutions and cultural life]

The Jewish population of Frankfort (col. 88)

numbered 3,298 in 1817 (7.9% of the total), 10,009 in 1871 (11%), 21,974 in 1900 (7.5%), and 29,385 in 1925 (6.3%). During the 19th century many Jews from the rural districts were attracted to the city whose economic boom owed much to Jewish financial and commercial enterprise. The comparative wealth of the Frankfort Jews is shown by the fact that, in 1900, 5,946 Jewish citizens paid 2,540,812 marks in taxes, while 34,900 non-Jews paid 3,611,815 marks.

Many civic institutions, including hospitals, libraries and museums, were established by Jewish donations, especially from the Rothschild family. The Jew Leopold *Sonnemann was the founder of the liberal daily Frankfurter Zeitung, and the establishment of the Frankfort university (1912) was also largely financed by Jews. Jewish communal institutions and organizations included two hospitals, three schools (the Philanthropin and the elementary and secondary schools founded by S.R. Hirsch), a yeshivah [[religious Torah school]] (founded by Hirsch's son-in-law and successor Solomon *Breuer), religious classes for pupils attending city schools, an orphanage, a home for the aged, many welfare institutions, and two cemeteries (the ancient cemetery was closed in 1828).

Frankfort Jews were active in voluntary societies devoted to universal Jewish causes, such as emigrant relief and financial support for the Jews in the Holy Land (donations from western Europe to the Holy Land had been channeled through Frankfort from the 16th century).

[[Normally all land on Earth is holy, but for many Jews only one little section of the Earth is "holy". This is one of the main faults of the Jewish religion, because all land on Earth is "holy"]].

The yearbook of the Juedisch-Literarische Gesellschaft [[Jewish Literature Association]] was published in Frankfort, and the Orthodox weekly Der Israelit [[The Israelite]] (founded in 1860) was published in Frankfort from 1906. The Jewish department of the municipal library, headed before World War II by the scholar A. *Freimann, had a rare collection of Hebraica and Judaica. During the first decade of the 20th century additional synagogues were erected, among them a splendid one situated at Friedberger Anlage [[Friedberg Park]]. In 1920 Franz *Rosenzweig set up an institute for Jewish studies, where Martin *Buber, then professor at the Frankfort university, gave popular lectures.

Two additional yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]] were established, one by Jacob *Hoffmann, who in 1922 succeeded Nehemiah Anton *Nobel in the Orthodox rabbinate of the community. Others prominent in Frankfort Jewish life include the writer Ludwig *Boerne; the historian I.M. *Jost; the artists Moritz *Oppenheim and Benno *Elkan; the biochemist Paul *Ehrlich; the economist and sociologist Franz *Oppenheimer; rabbis Jacob *Horowitz and Joseph *Horowitz (Orthodox); Leopold Stein, Nehemiah Bruell, Caesar *Seligmann (Reform); and the Orthodox leaders Jacob *Rosenheim and Isaac *Breuer.

[M.BRE.]> (col. 89)

[[The years from 1920 to 1930 are not mentioned in this article. Probably there was

-- a massive frustration after the Versailles Treaty of 1919 and Jews were blamed for it

-- an invasion of East European Jews which was not positive for the reputation of the community

-- nationalism was also expressing with racist Zionism and their counter part, the Jewish anti-Zionists

-- and all rich Jewish families converted into an enemy of the general population after the hyper inflation of 1923 and after the collapse of the stock exchange in 1929]].

<Printing.

In the first half of the 19th century the names of seven non-Jewish printing houses are known. Subsequently Jewish printers emerged for the first time. Among (col. 91)

them were J.H. Golda (1881-1920), E. Slobotzki (from 1855), and the bookseller J. Kauffmann, who took over the *Roedelheim press of M. Lehrberger in 1899. Hebrew printers were active in places like *Homburg, *Offenbach, *Sulzbach, Roedelheim, and others in the neighbourhood of Frankfort, because Jewish printers were unable to establish themselves in Frankfort.

[ED.]> (col. 92)

<Music.

In the 19th century the Reform movement installed an organ in the main Frankfort synagogue, whereupon the Orthodox congregation introduced a male choir in their own synagogue with I.M. *Japhet as musical director.> (col. 92)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter |

Č Ḥ ¦

Ṭ Ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

ā ć č ḥ ī ¨ ū ¸ ẓ

^

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on

the Main, vol. 7, col. 90, the synagogue at the

Boerneplatz [[Boerne Square]], consecrated in 1882.

Israel Museum Archives, Jerusalem Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on the

Main, vol. 7, col. 90, the synagogue at the

Boerneplatz [[Boerne Square]], consecrated in 1882.

Israel Museum Archives, Jerusalem](EncJud_juden-in-Frkft-Main-d/EncJud_Frankfurt-am-Main-band7-kolonne90-syn-Boerneplatz1882-44pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica

(1971): Frankfort on the Main, vol. 7, col. 89,

drawing of the synagogue on the Boernestrasse,

[[Boerne Street]], built in 1855-60 and burned down

in 1938. Courtesy Frankfort Historical Museum Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Frankfort on the

Main, vol. 7, col. 89, drawing of the synagogue on

the Boernestrasse, [[Boerne Street]], built in

1855-60 and burned down in 1938. Courtesy Frankfort

Historical Museum](EncJud_juden-in-Frkft-Main-d/EncJud_Frankfurt-am-Main-band7-kolonne89-syn-Boernestr1860-1938-55pr.jpg)

previous

previous