Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Cracow 02: 16th and 17th century

Jewish influx from Bohemia-Moravia, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal - estate and trade regulations - schooling, rabbis, Shabbateans, and reform movement - invasions and taxes

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Cracow, vol. 5, col. 1035. Doors of an Ark of the Law, Cracow, early 17th century.

Painted lead on wood, 4 3/4 to 1 1/8 ft. (46 to 34 cm). Jerusalem, Israel Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem

from: Cracow; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 5

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2020)

Share:

<16th Century.

[Jewish influx from Bohemia-Moravia - two communities with two rabbis - unification of the communities - Jewish influx from Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal - tax privileges for the rich newcomers]

At the beginning of the 16th century many Jews from Bohemia-Moravia settled in Kazimierz,but their desire to retain their separate cohesion and style of life was opposed by the Polish Jews, led by the *Fishel family. In the overcrowded conditions of the Jewish town tension between the two groups led to bitter conflict.

After the resignation of Jacob Pollak from the Cracow-Kazimierz rabbinate the Polish congregation elected Asher Lemel, a friend of the Fishel family, while the Bohemian Jews elected another rabbi. In 1509 the king imposed financial sureties on both parties to compel them to maintain the peace.

In 1519 he recognized the two congregations as autonomous communities, each electing its own rabbi, two elders, and a mediator to collaborate in the administration of the Jewish town. After the deaths of the two rival rabbis, this duality disappeared and the rabbinate was transferred to Moses Fishel of the Polish section.

In addition to those from Bohemia-Moravia a large number of immigrants arrived in Kazimierz in the 16th century from Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal [[by expulsions in Germany, Spain (1492) and Portugal (1498). These included wealthy men and physicians, some of whom acquired special personal privileges from the king of Poland exempting them from their financial obligations as members of the Jewish community. It was only in 1563, after numerous appeals from the communal leaders, that the king undertook to cease this practice.

[Amplification of the Jewish quarter Kazimierz]

Intensification of the overcrowding resulted in 1553 in official agreement to a small extension of the Jewish town and permission for the erection of a second synagogue. In 1564 a privilege was granted preventing non-Jews from acquiring residential or business premises in the Jewish town. By the 1570s, the Jewish population of Kazimierz numbered 2,060, and further extension of the Jewish quarter became urgent. In 1583 an agreement between the community and the municipality of Kazimierz on the expansion of the Jewish area was ratified by the king. The Jews undertook to erect the Bochnia Gate in the city walls and to liquidate the arrears in tax payments to the municipal treasury.

17th Century.

[Jewish right to acquire real estate since 1608 and erected Jewish houses - trade agreement of 1609 - "Christian" fears and royal decisions for Jewish trade]

In 1608 the king ratified an agreement with the municipality on the sale of an additional number of building sites and houses to Jews in return for an annual payment of 250 zlotys by the community to the municipality. The attempt of the community to retain control over the new acquisitions of real estate failed because of opposition from both Jews and Christians, and Jews were permitted to acquire real estate individually.

By 1635, 67 houses, mainly occupied by wealthy persons (Isaac *Jekeles, Wolf *Popper, among others), had been erected in the section recently joined to the Jewish town.

Throughout this period, the fierce struggle for Jewish commercial rights continued, in particular when Jewish traders had "invaded" the Christian sectors. In 1609 the community reached an agreement which in practice enabled the Jews to trade freely in Kazimierz and nearby Stradom, to rent shops and warehouses in the Christian city, and to engage in the fur and tailoring crafts for supply of their own requirements. They were prohibited from innkeeping and trade in fodder. Jewish economic activity within the limits of Cracow proper was dependent on bribery and the search for patrons among government and church circles or within the municipal (col. 1028)

council.

While Christian property owners of Cracow were interested in Jewish trade in the town because they could lease warehouses and shops to Jews at exorbitant prices, the small tradesmen and craftsmen regarded the Jews as dangerous rivals. In 1576 the king had recognized the Jewish trade existing in the town through granting his protection to the practice. The struggle continued with varying success for both sides. The campaign against Jewish trade in Cracow was expressed in the polemic literature of the period in an anti-Jewish pamphlet by Sebastian *Miczyński. However, despite the influence of this tract and anti-Jewish outbreaks, Jewish trade in Cracow developed further in the 17th century, and was recognized de facto by royal decisions.

[Cultural life in 16th and 17th century: schooling - rabbis - Shabbatean and reform movement]

The 16th and first half of the 17th century was also a period of considerable cultural achievement in the Cracow-Kazimierz community. By 1644 the community had seven main synagogues, among them the Alte Schul [[Old School]] and the Rema Synagogue (called after Moses *Isserles), erected in part by private persons and in one case with contributions from the goldsmiths' guild. From the second half of the 16th century a number of yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]] were founded in Kazimierz whose fame made Cracow a most important center of Jewish learning. Among principals of the yeshivot during the second half of the 16th century were Moses Isserles, Mordecai b. Jacob of Cieplice, Joseph b. Gershon Katz, Nathan Nata *Shapiro, Joshua b. Joseph *Katz, Isaac b. David ha-Kohen Shapira, *Meir Gedaliah of Lublin, and Joel *Sirkes. About the middle of the 17th century Yom Tov Lippman *Heller was rabbi there.

In 1666 the Shabbatean movement deeply stirred Cracow Jewry. The reformation movement among the Cracow burghers gave rise to charges of Judaizing, both true and unfounded, against its own radical wing. An earlier martyr of such accusations was Catherine *Weigel. The religious ferment and strife among the Christians made a strong impression on the Cracow Jews.

Communal Organization.

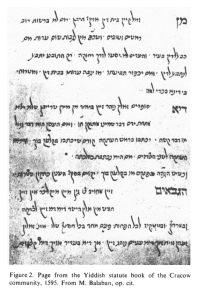

By the end of the 16th century the patrician class had gained an oligarchic control of the communal administration mainly due to the exclusive system of elections. A statute for the community was formulated through various enactments, known after its main corpus as "the ordinances of (5)355" (i.e. the year 1595; cf. M. *Balaban: "Die Krakauer Judengemeinde-Ordnung von 1595 und ihre Nachtraege", in JJLG, 10 (1913), 296-360; 11 (1916), 88-114).

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Cracow, vol. 5, col. 1031. Page from the Yiddish statute book of the Cracow community, 1595. From M. Balaban, op. cit.

The community was headed by four rashim ("heads"), five tovim ("boni vires" or "notables"), and 14 kahal ("community council") members, a total of 23 leaders, i.e., the number constituting a "minor Sanhedrin". The duties of actual administration and supervision were assumed in rotation; every month one of the rashim publicly took an oath to fulfill his duties as parnas ha-hodesh (ḥodesh) ("leader for the month") conscientiously. (col. 1029)

Defined competencies and functions were assigned to other institutions of the community leadership. The community had numerous functionaries, some honorary and some paid, most of whom worked in committees and were allocated specific tasks, such as tax assessment, supervision of charity, and public market order. The persistent oligarchic trend inherent in the 1595 ordinances is shown in their regulation of judicial procedure which reveals a hierarchical system of three law courts, whose competence was graded according to the sums involved in the case, and payment was made to the two lower ones by both sides. These arrangement differ from strict halakhic conceptions of judicial practice.

[Cracow-Kazimierz council of Lesser Poland]

Cracow-Kazimierz was one of the principal communities in the *Councils of the Lands; it headed the province (galil) of Lesser Poland. Taxes to the state were paid through and in conjunction with the Councils of the Lands (see also *Poland-Lithuania). Provision for the regulation of internal taxation for providing defense against local persecution, for upkeep of officials, official functions, and charity is made in the 1595 ordinances and others (see B.D. Weinryb, "Texts and Studies in the Communal History of Polish Jewry", in PAAJR, 19 (1950), 77-98).

[Jewish refugees from Germany and Ukraine and Podolia]

In the 1630s large numbers of Jews fled from Germany to Cracow during the Thirty Years' War. In addition, many others from Ukraine and Podolia sought refuge in Cracow in 1648-49 from the *Chmielnicki massacres.

[Swedish invasion of 1655 - Polish pogrom - collaboration libel - tax and fine imposed - riots and pogroms]

The second half of the 17th century was a troubled period for the Cracow community. It suffered during the Swedish invasion, and in 1655, when Kazimierz was captured, many Jews fled. The Poles commanded by Stefan *Czarniecki looted Jewish shops and property, causing damage estimated at 700,000 zlotys. Much harm was also done to Jewish property during the two-year Swedish occupation. With the restoration of Polish rule, a monetary contribution was imposed on the Jewish community, who were accused of collaborating with the Swedes.

The Jews of Cracow first had to pay large sums to the Polish army commanders, and, in the fall of 1657, 60,000 zlotys to the king; they were also charged 300 zlotys a week toward maintenance of the fortress garrison and the municipal guard, and were fined 10,000 zlotys following an accusation that they had handed over sacred objects from the cathedral to the Swedes. The Kazimierz Jews were excluded from Cracow under various pretexts.

During this period, attacks on Jewish houses by the students and the local population became increasingly frequent, while the royal authorities were powerless to take action against them. There were a number of blood libels. In 1663 Mattathias *Calahora was martyred at the stake. In 1664, the anti-Jewish outbreaks reached a new climax and intervention by the king and the fines imposed on the municipal council proved unavailing. In 1677 about 1,000 Jews in Kazimierz died of plague and the Jewish quarter was abandoned by most of its inhabitants. The stricken community could not pay its taxes; by 1679 the arrears of the poll-tax payments amounted to 50,000 zlotys and the king had to grant the Cracow community a moratorium on its taxes and other debts.

The community began to reorganize in 1680 and reopened its yeshivah [[religious Torah school]], but in 1682 anti-Jewish rioting by the populace and students again broke out accompanied by murder and looting, and army units had to be called in. The king punished the rioters severely and imposed heavy fines on the university, and the Jews were granted a further moratorium on their debts to the state treasury and individuals.

[Anti-Jewish "Christian" population - restrictions]

The Cracow citizenry renewed its demands that Jews would be prohibited from practicing trade and crafts on the basis of the 1485 agreement (see above). Jews were prevented from entering (col. 1030)

Cracow on Sundays and Christian festivals. The most outstanding of the community's rabbis in the second half of the 17th century was Aaron Samuel *Koidanover. (col. 1031)

Hebrew Printing in Cracow. [part 1]

Hebrew printing was first introduced in Cracow in 1534 by the brothers Samuel, Asher, and Eliakim Haliecz, who had learned the craft with Gershom Kohen in Prague, whose style their productions betray. They printed the first edition of Isaac of Dueren's Sha'arei Dura - in Rashi type and with a beautifully decorated title page - in 1534, the year in which they received a license from King Sigismund I of Poland. A few other works followed, until in 1537 the three brothers converted to Christianity, which did not prevent them from continuing to print Hebrew books (a mahzor (maḥzor) [[prayer book for high holidays]] and the first two parts of the Tur), but (col. 1037)

their products were boycotted by the Jewish community. Eventually the king forced the Jewish communities of Cracow, Poznan, and Lvov to buy the Halicz's entire stock.

Great success was attained by the Hebrew press set up in 1569 by Isaac b. Aaron of Prostitz (Prossnitz), who was trained in Italy and received a 50 years' license from Sigismund II Augustus. He acquired his equipment from the Venetian printers Cavalli and Grypho and also brought with him from Italy the scholarly proofreader Samuel Boehm. In the next 60 years Isaac and his successors (sons and nephews) produced some 200 books, of which 73 were in Yiddish.

The Babylonian Talmud was printed twice (1602-08; 1616-20); a fine edition of the Jerusalem Talmud in 1609; Alfasi's Halakhot together with Mordekhai in 1598; and several editions of the Shulhan (Shulḥan) Arukh with Isserles' annotations.

Among kabbalistic literature was a Zohar (1603), and some of Moses Cordovero's writings. Other works included a Pentateuch and haftarot [[Prophet books sung in the service]] with the classical commentaries (1587), Yalkut Shimoni (1596), and Ein Ya'akov (1587, 1614, 1619). In his title-page decoration Isaac copied the Italian style. His printer's mark was first a hart, but from 1590 fishes. For the next four decades (1630-70), prominent Hebrew printers in Cracow were Menahem Nahum Meisels, his daughter Czerna, and his son-in-law Judah Meisels, a grandson of Moses Isserles. Menahem Nahum took over Isaac b. Aaron's equipment which he enlarged and improved, but he returned to the Prague style of printing, with Judah ha-Kohen of Prague as his manager.> (col. 1038)

Č Ḥ Ł ¦ Ṭ Ẓ Ż

ā ć č ẹ ȩ ę ḥ ī ł ń ś ¨ ū ¸ ż ẓ

^