Jews in Poland 01:

colonization of Poland-Lithuania by Jews

Jewish settlers - moneylending and trade with

connections between Germany, Poland, and the Ottoman

Empire - cultural life and disputes - Christian resistance

and Jewish towns

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

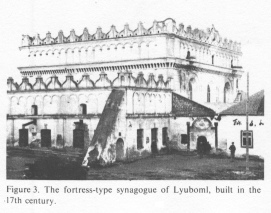

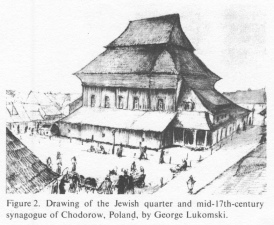

Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. The fortress-type

synagogue of Lyuboml, built in the 17th century.

from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 13

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2020)

<POLAND [[...]]

ECONOMIC ACTIVITY.

[Moneylending and agriculture

- cemetery is paid with spices in 1287 - trade in grand

duchy of Lithuania and Poland with Genoese colonies in

Crimea and with Constantinople]

From the very first the Jews of Poland developed their

economic activities through moneylending toward a greater

variety of occupations and economic structures. Thus, by the

very dynamics of its economic and social development, Polish

Jewry constitutes a flat existential denial and factual

contradiction of the anti-Semitic myth of "the Jewish spirit

of usury". On the extreme west of their settlement in Poland,

in Silesia, although they were mainly engaged in moneylending,

Jews were also employed in agriculture.

When the Kalisz community in 1287 bought a cemetery it

undertook to pay for it in pepper and other oriental wares,

indicating an old connection with the trade in spices. As

noted above, the Jewish mintmasters of the 12th century must

undoubtedly have been large-scale traders. In 1327 Jews were

an important element among the participants at the *Nowy Sacz

fair. Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries Jews were

occupied to a growing degree in almost every branch of trade

pursued at that time. Jews from both the grand duchy of

Lithuania and Poland traded in cloth, dyes, horses, and cattle

(and on a fairly large scale).

At the end of the 15th century they engaged in trade with

Venice, Italy, with Kaffa (Feodosiya), and with other (col.

717)

Genoese colonies in the Crimea, and with Constantinople.

[Jewish large-scale

land-transit trade between Europe and Ottoman Empire - trade

up to Moscow - rich Jews lend money to the government]

Lvov Jews played a central role in this trade, which in the

late 15th and early 16th centuries developed into a

large-scale land-transit trade between the Ottoman Empire and

Christian Europe. Through their participation in this trade

and their contacts with their brethren in the Ottoman Empire,

many Jewish communities became vital links in a trade chain

that was important to both the various Christian kingdoms and

the Ottoman Empire. Lithuanian Jews participated to the full

and on a considerable scale in all these activities, basing

themselves both on their above-mentioned recognized role in

Lithuanian civic society and on their particular opportunities

for trade with the grand principality of *Moscow and their

evident specialization in dyes [[colors]] and dyeing

[[coloring]]. Obviously, in all these activities, all links

with Jewish communities in central and western Europe were

beneficial.

During all this period Jews were engaged in moneylending, some

of them (e.g., *Lewko Jordanis, his son Canaan, and Volchko)

on a large scale. They made loans not only to private citizens

but also to magnates, kings, and cities, on several occasions

beyond the borders of Poland. The scope of their monetary

operations at their peak may be judged by the fact that in

1428 King Ladislaus II Jagello accused one of the Cracow city

counselors of appropriating [[using]] the fabulous sum of

500,000 zlotys which the Jews had supplied to the royal

treasury.

[Financial assistance to the

court - Jews are chosen for colonization projects - customs

rights and salt rights - Jews become a "third estate" in the

cities - complaints because of unfair trade - deprivation of

rights - expulsion from Cracow to Kazimierz in 1495]

To an increasing extent many of the Jewish moneylenders became

involved in trade. They were considered by their lords as

specialists in economic administration. In 1425 King Ladislaus

II Jagello charged Volchko - who by this time already held the

Lvov customs lease - with the colonization of a large tract of

land:

"As we have great confidence in the wisdom, carefulness, and

foresight of our Lvov customs-holder, the Jews Volchko ...

after the above-mentioned Jew Volchko has turned the

above-mentioned wilderness into a human settlement in the

village, it shall remain in his hands till his death."

King Casimir Jagello entrusted to the Jews Natko both the salt

mines of Drohbycz (*Drogobych) and the customs station of

Grejdek, stating in 1452 that he granted it to him on account

of his "industry and wisdom so that thanks to his ability and

industry we shall bring in more income to our treasury."

The same phenomenon is found in Lithuania. By the end of the

15th century, at both ends of the economic scale Jews in

Poland were becoming increasingly what they had been from the

beginning in Lithuania: a "third estate" in the cities.

The German-Polish citizenry quickly became aware of this. By

the end of the 15th century, accusations against the Jews

centered around unfair competition in trade and crafts more

than around harsh usury. Not only merchants but also Jewish

craftsmen are mentioned in Polish cities from 1460 onward. In

1485 tensions in Cracow was so high that the Jewish community

was compelled to renounce [[give up]] formally its rights to

most trades and crafts. Though this was done "voluntarily",

Jews continued to pursue their living in every decent [[living

properly]] way possible. This was one of the reasons for their

expulsion from Cracow to Kazimierz in 1495. However, the end

of Jewish settlement in Cracow was far from the end of Jewish

trade there; it continued to flourish and aggravate [[be

harder]] the Christian townspeople, as was the case with many

cities (like *Lublin and *Warsaw) which had exercised their

right de non tolerandis

Judaeis and yet had to see Jewish economic activity

flourishing at their fairs and in their streets.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL LIFE.

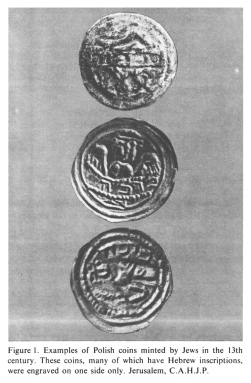

In Poland and Lithuania from the 13th century onward Jewish

culture and society was much richer and more (col. 718)

variegated than has been commonly accepted. Even before that,

the inscriptions on the bracteate coins [[important coins]] of

the 12th century indicate talmudic culture and leadership

traditions by the expressions used (rabbi, nagid).

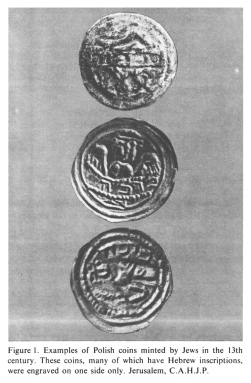

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. Examples of

Polish coins minted by Jews

in the 13th century. These coins, many of which have Hebrew

inscriptions,

were engraved on one side only. Jerusalem, C.A.H.J.P.

About 1234, as mentioned, Jacob Savra of Cracow was able to

contradict the greatest talmudic authorities of his day in

Germany and Bohemia. In defense of his case he "sent responsa

to the far ends of the west and the south" (E.E. Urbach (ed.),

in Sefer Arugat ha-Bosem,

4 (1963), 120-1). The author of Sefer Arugat ha-Bosem also quotes an

interpretation and emendation [[amelioration]] that "I have

heard in the name of Rabbi Jacob from Poland" (ibid., 3

(1962), 126).

Moses Saltman, the son of *Judah b. Samuel he-Hasid (Ḥasid),

states:

"Thus I have been told by R. Isaac from Poland in the name of

my father ... thus I have been told by R. Isaac from Russia

... R. Mordecai from Poland told me that my father said" (Ms.

Cambridge 669, 2, fol. 69 and 74). This manuscript evidence

proves conclusively that men from Poland and from southern

Russia (which in the 13th century was part of the grand duchy

of Lithuania) were (col. 719)

close disciples of the leader of the *Hasidei (Ḥasidei)

Ashkenaz.

[Names from German, French

and Czech culture - Jewish calendar]

The names of Polish Jews in the 14th century show curious

traces of cultural influence; besides ordinary Hebrew names

and names taken from the German and French - brought by the

immigrants from the countries of their origin - there are

clearly Slavonic names like Lewko, Jeleń, and Pychacz and

women's names like Czarnula, Krasa, and even Witoslawa. Even

more remarkable are the names of Lewko's father, Jordan, and

Lewko's son, Canaan or Chanaan, which indicate a special

devotion to Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of Israel]].

By the 15th century, relatively numerous traces of social and

cultural life in the Polish communities can be found. In a

document from April 4, 1435, that perhaps preserves the early

*Yiddish of the Polish Jews, the writer, a Jews of Breslau,

addresses "the Lord King of Poland my Lord". The closing

phrases of the letter indicate his Jewish culture:

"To certify this, have I, the above mentioned Jekuthiel,

appended my Jewish seal to this letter with full knowledge.

Given in Breslau, on the first Monday of the month Nisan, in

Jewish reckoning five thousand years and a hundred (col. 720)

years and to that hundred the ninety-fifth year after the

beginning and creation of all creatures except God Himself"

(M. Brann: Geschichte der Juden in Schlesien [[History of the

Jews in Silesia]], 3 (1901), Anhang [[appendix]] 4, p. Iviii).

Though Israel b. Hayyim (Ḥayyim) *Bruna said of the Jews of

Cracow, "they are not well versed in Torah" (Responsa, no. 55,

fol. 23b), giving this as his reason for not adducing lengthy

talmudic arguments in his correspondence with them, he was

writing to one of his pupils who claimed sole rabbinical

authority and income in the community of Poznan (ibid., no.

254, fol. 103b). Israel b. Pethahiah *Isserlein of Austria

writes, "my beloved, the holy community of Poznan". Two

parties in this community - the leadership, whom Isserlein

calls "you, the holy community", and an individual were

quarreling about taxation and Isserlein records that both

sides submitted legal arguments in support of their cases (Terumat ha-Deshen, Pesakim

u-Khetavim, no. 144).

[Scholars and Jewish cultural

life in Poland]

Great scholars like Yom Tov Lipmann *Muelhausen, who came to

Cracow at the end of the 14th century, and Moses b.

Isaac Segal *Mintz, who lived at Poznan in 1475, must

certainly have left traces of their cultural influence there.

Some of the responsa literature contains graphic descriptions

of social life.

"A rich man from Russia" - either the environs of Lvov in

Poland or of Kiev in Lithuania - asked Israel Bruna,

"If it is permissible to have a prayer shawl of silk in red or

green color for Sabbath and the holidays" (Responsa, no. 73,

fol. 32b), a desire fitting a personality of the type of

Volchko.

Something of the way of life of "the holy company of Lvov" can

be seen from the fact that their problem was the murder of one

Jew by another in the Ukrainian city of

*Pereyaslav-Khmelnitski. As the victim lay wounded on the

ground, a third Jew, Nahman (Naḥman), called out to the

murderer, Simhah (Simḥah): "Hit Nisan till death" and so

he was killed by being beaten on his head as he lay there

wounded. The victim was a totally ignorant man, "he couldn't

recognize a single [Hebrew] letter and has never in his life

put on tefillin."

The murderer was drunk at the time and the victim had started

the quarrel; they were all in a large company of Jews (ibid.,

no. 265, fol. 110a-b).

The large rough social and cultural climate of Jewish traders

in the Ukraine in the middle of the 15th century is here in

evidence. Moses Mintz describes from his own experience

divorce customs in the region of Poznan (Responsa (Salonika,

1802), no. 113, fol. 129b). He also describes interesting

wedding customs in Poland which differed in many details from

those of Germany:

"when they accompany the bride and bridegroom to the huppah (ḥuppah) they sing

on the way ... they give the bridegroom the cup and he throws

it down, puts his foot on it and breaks it, but they pour out

the wine from the cup before they give it to the bridegroom.

They have also the custom of throwing a cock and also a hen

over the head of the bride and bridegroom above the canopy

after the pronouncing of the wedding blessings" (ibid., no.

109, fol. 127a).

Thus, in the western and central parts of Poland there is

evidence of an established and well developed culture and some

learning, contrasting sharply with the rough and haphazard

[[arbitrary]] existence of Jews living southwards from Lvov to

Pereyaslav-Khmelnitski.

[Jewish culture in Lithuania]

Jewish culture in Poland and in Lithuania seems to have had a

certain rationalist, "Sephardi" tinge [[color]], as evidenced

both by outside reports and by certain tensions appearing in

the second half of the 16th century. At the beginning of the

(col. 721)

16th century the Polish chronicler Maciej Miechowicz relates

that in Lithuania,

"the Jews use Hebrew books and study sciences and arts,

astronomy and medicine" (Tractatus

de duabus Sarmatiis (1517), II:1,3). The cardinal

legate Lemendone also notes that Lithuanian Jews of the 16th

century devote time to the study of "literature and science,

in particular astronomy and medicine". At the end of the 15th

century, Lithuanian Jews took part in the movement of the

"Judaizers in Muscovite Russia, whose literature shows a

marked influence of rationalistic Jewish works and

anti-Christian arguments.

The Jewish community of Kiev - in the 15th and early 16th

centuries within the grand duchy of Lithuania - was praised by

a Crimean Karaite in 1481 for its culture and learning. In

about 1484 another Karaite, Joseph b. Mordecai of Troki, wrote

a letter to Elijah b. Moses *Bashyazi (Mann, Texts, 2 (1935),

1149-59) telling about a disputation on calendar problems

between him and "the Rabbanites who live here in Troki, Jacob

Suchy of Kaffa (Feodosiya) and Ozer the physician of Cracow"

(ibid., 1150). He closes his letter with ideas showing a

decided rationalist tendency,

"The quality of the sermon will be through the quality of the

subject, therefore as we have none such more important than

the Torah, for in it there is this teaching that brings man

straight to his scientific and social success and the chief of

its considerations is that man should achieve his utmost

perfection, which is spiritual success; and this will happen

when he attains such rational concepts as the soul, the active

reason, can attain, for the relation between a phenomenon and

its causes is a necessary relation, i.e., the relation of the

separate reason to the material reason is like the relation of

light to sight" (ibid., 1159).

[Jewish philosophic dispute

in 16th century in Poland: Solomon Luria and Moses Isserles

- pupil Abraham b. Shabbetai Horowitz]

In Poland a dispute between two great scholars of the 16th

century - Solomon *Luria and Moses *Isserles - brings to the

surface elements of an earlier rationalist culture. Luria

accuses yeshivah students [[students of a religious Torah

school]] of using "the prayer of Aristotle" and accuses

Isserles of "mixing him with words of the living God...

[considering] that the words of this unclean one are precious

and perfume to Jewish sages" (Isserles, Responsa, no. 6).

Isserles replies:

"All this is still a poisonous root in existence, the legacy

from their parents from those that tended to follow the

philosophers and tread in their steps. But I myself have never

seen nor heard up till now such a thing, and, but for your

evidence, I could not have believed that there was still a

trace of these conceptions among us" (ibid., no. 7).

Writing around the middle of the 16th century, Isserles tells

unwittingly of a philosophizing rend prevalent in Poland many

years before. A remarkable case of how extreme rationalist

conceptions gave way to more mystic ones can be seen in

Isserles' pupil, Abraham b. Shabbetai *Horowitz.

Around 1539 he sharply rebuked the rabbi of Poznan, who

believed in demons and opposed *Maimonides:

"As to what this ass said, that it is permissible to study

Torah only, this is truly against what the Torah says, 'Ye

shall keep and do for it is your wisdom and understanding in

the eyes of the gentiles.' For even if we shall be well versed

in all the arcana of the Talmud, the gentiles will still not

consider us scholars; on the contrary, all the ideas of the

Talmud, its methods and sermons, are funny and derisible in

the eyes of the gentiles. If we know no more than the Talmud

we shall not be able to explain the ideas and exegetical

methods of the Talmud in a way that the gentiles will like -

this stands to reason" (See MGWJ, 47 (1903), 263).

Yet this same man rewrote his rationalistic commentary on a

work by Maimonides to make it more amenable to

traditionalistic and mystic thought, declaring in the second

version, "The first uproots, the last roots". Later trends and

struggles in Jewish culture in Poland and Lithuania are partly

traceable (col. 722)

to this early and obliterated rationalistic layer (see below).

[Polish expansion in Ukraine

and Belorussia since 1550 - Poland-Lithuania since 1569]

Polish victories over the Teutonic Order in the west and

against Muscovite and Ottoman armies in the east and southeast

led to a great expansion of Poland-Lithuania from the second

half of the 16th century. IN this way Poland-Lithuania gained

a vast steppeland in the southeast, in the Ukraine fertile but

unpacified and unreclaimed, and great stretches of arable

[[fertile]] land and virgin forest in the east, in Belorussia.

The agricultural resources in the east were linked to the

center through the river and canal systems and to the sea

outlet in the west through land routes. These successes forged

a stronger link between the various strata of the nobility

(Pol. szlachta) as

well as between the Polish and Lithuanian nobility.

In 1569 the Union of Lublin cemented and formalized the unity

of Poland-Lithuania, although the crown of Poland and the

grand duchy of Lithuania kept a certain distinctness of

character and law, which was also apparent in the *Councils of

the Lands and in the culture of the Jews (see below). With the

union, Volhynia and the Ukraine passed from the grand duchy to

the crown. The combined might of Poland-Lithuania brought

about a growing pacification of these southeastern districts,

offering a possibility of their colonization which was eagerly

seized upon by both nobility and peasants.

1569-1648: COLONIZATION OF THE UKRAINE.

[Life under Polish nobility -

experienced Jews as "partners" - and Christian resistance -

aggressive Jews - Jewish connections Germany-Poland-Ottoman

Empire]

The Polish nobility, which became the dominant element in the

state, was at that time a civilized and civilizing factor.

Fermenting with religious thought and unrest which embraced

even the most extreme anti-trinitarians; warlike and at the

same time giving rise to small groups of extreme anarchists

and pacifists; more and more attracted by luxury, yet for most

of the period developing rational - even if often harsh -

methods of land and peasant exploitation; despising

merchandise yet very knowledgeable about money and gain - this

was the nobility that, taking over the helm of state and

society, developed its own estates in the old lands of

Poland-Lithuania and the vast new lands in the east and

southeast.

Jews soon became the active and valued partners of this

nobility in many enterprises. In the old "royal cities" - even

in central places like Cracow, which expelled the Jews in

1495, and *Warsaw, which had possessed a privilegium de non tolerandis

Judaeis since 1527 - Jews were among the great

merchants of clothing, dyes [[colors]], and luxury products,

in short, everything the nobility desired.

Complaints from Christian merchants as early as the beginning

of the 16th century, attacks by urban anti-Semites like

Sebastian *Miczyński and Przecław *Mojecki in the 17th

century, and above all internal Jewish evidence all point to

the success of the Jewish merchant.

The Jews prospered in trade even in places where he could not

settle, thanks to his initiative, unfettered [[liberated]] by

guilds, conventions, and preconceived notions [[with big

plans]]. The kesherim,

the council of former office holders in the Poznan community,

complain about the excessive activity of Jewish

intermediaries, "who cannot stay quiet; they wait at every

corner, in every place, at every shop where silk and cloth is

sold, and they cause competition through influencing the

buyers by their speech and leading them to other shops and

other merchants." The same council complains about "those

unemployed" people who sit all day long from morning till

evening before the shops of gentiles - of spice merchants,

clothes merchants, and various other shops - "and the

Christian merchants complain and threaten". There was even a

technical term for such men, tsuvayzer [[Yidd.: pointer]], those who

point the way to a prospective seller (Pinkas Hekhsherim shel Kehillat

Pozna, ed. D. Avron (1966), 187-8, no. 1105, 250 no.

1473, 51 no. 1476).

Miczyński gives a bitter description of the same phenomenon in

Cracow in 1618. (col. 723)

Large-scale Jewish trade benefited greatly from the trader's

connections with their brethren both in the Ottoman Empire and

in Germany and Western Europe. It was also linked to a

considerable extent with the *arenda system and its resulting

great trade in the export of agricultural products.

[New Jewish agricultural

settlements in Ukraine by Arenda program - professions -

Tatar resistance]

Through the arenda system Jewish settlements spread over the

country, especially in the southeast. Between 1503 and 1648

there were 114 Jewish communities in the Ukraine, some on the

eastern side of the River Dnieper (see map and list by S.

Ettinger, in: Zion, 21 (1956), 114-8); many of these were

tiny. Table 1 shows the main outlines of the dynamics of

Jewish settlement in these regions of colonization (ibid., p.

124):

Table 1.

Growth of Jewish Settlement by Places and Numbers

in the Colonization Period

|

Wojewódstwo

(district)

|

Before

1569

|

|

c.

1648

|

|

|

|

Places

|

Numbers

|

Places

|

Numbers

|

|

Volhynia

|

13xxxxxx

|

3,000xxxxx |

46xxxxx |

15,000xxxxxx |

|

Podolia

|

9xxxxxx |

750xxxxx |

18xxxxx |

4,000xxxxxx |

|

Kiev

|

-xxxxxx |

-xxxxx |

33xxxxx |

13,500xxxxxx |

32,325

|

Bratslav

|

2xxxxxx |

?xxxxx |

18xxxxx |

18,825xxxxxx |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

24xxxxxx |

c.

4,000xxxxx |

115xxxxx |

51,325xxxxxx |

|

from: from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica

1971, vol. 13, col. 724

|

The further the move east and southward, the greater the

relative growth in numbers and population. The Jewish arenda

holders, traders, and peddlers traveled and settled wherever

space and opportunity offered.

Life in these districts was strenuous and often harsh. The

manner of Jewish life in the Ukraine, which as we have already

seen was uncouth [[rough]], was both influenced and channeled

through Jewish participation in the defense of newly pacified

land. Meir b. Gedaliah of Lublin relates

"what happened to a luckless man, ill, and tortured by pain

and suffering from epilepsy ... When there was an alarm in

Volhynia because of the Tatars - as is usual in the towns of

that district - when each one is obliged to be prepared, with

weapon in hand, to go to war and battle against them at the

command of the duke and the lords; and it came to pass that

when the present man shot with his weapon, called in German Buechse [[tin]], from his

house through the window to a point marked for him on a rope

in his courtyard to try the weapon as sharpshooters are wont

to do, then a man came from the market to the above mentioned

courtyard ... and he was killed [by mistake]."

The rabbi goes on to tell that a Christian, the instructor and

commander of this Jew, was standing in front of the courtyard

to warn people not to enter. The Jew was "living among the

gentiles in a village" with many children (Meir b. Gedaliah of

Lublin, Responsa, no. 43).

[Alcohol trade - Jews in the

Cossack army - daily violence]

There is reference to an enterprising group of Jews who went

to Moscow with the armies of the Polish king during war,

selling liquor (one of them had two cartloads) and other

merchandise to the soldiers (ibid., no. 128).

Among the Cossack units there was a Jews about whom his

Cossack colleagues "complained to God ... suddenly there

jumped out from amongst our ranks a Jews who was called

Berakhah, the son of the martyr Aaron of Cieszewiec."

This Jews was not the only one in the ranks of the Cossacks,

for - to allow his wife to marry - one of the witnesses says

that "he knew well that in this unit there was not another

Jewish fighter who was called Berakhah" (ibid., no. 137).

Life in general was apt [[tended]] to be much more violent

than is usually supposed: even at Brest-Litovsk, when the rebbe [[private teacher]]

of the community saw a litigant [[head of the court]] nearing

his door, he seized a heavy box and barricaded himself in for

fear of harm (ibid., no. 44). (col. 724)

[Mill rights, alcohol rights,

and milk rights - sabbath resolution in Volhynia in 1602]

Arenda did more than give a new basis to the existence of many

Jewish families; it brought the Jews into contact with village

life and often combined with aspects of their internal

organizational structure. Thus, the Jews Nahum b. Moses, as

well as renting the mills, the tavern, and the right of

preparing beer and brandy, also rented for one year all milk

produce of the livestock on the manors [[knight's

territories]] and villages. Elaborate and complicated

arrangement were made for payment and collection of these milk

products (S. Inglot, in: Studja

z historji spolecnej i gospodarczej poświȩcone prof.

Franciszkowi Bujakowi (1931), 179-82; cf. 205,

208-9). In contact with village life, the Jews sometimes

formed a sentimental attachment to his neighbors and his

surroundings.

In 1602 a council of leaders of Jewish communities in Volhynia

tried to convince Jewish arendars to let the peasants rest on

Saturday though the Polish nobleman would certainly have given

them the right to compel them to work:

"If the villagers are obliged to work all the week through, he

should let them rest on Sabbath and the Holy Days throughout.

See, while living in exile and under the Egyptian yoke, our

parents chose this Saturday for a day of rest while they were

not yet commanded about it, and heaven helped them to make it

a day of rest for ever. Therefore, where gentiles are under

their authority they are obliged to fulfill the commandment of

the Torah and the order of the sages not to come, God forbid,

to be ungrateful [livot]

to the One who has given them plenty of good by means of

the very plenty he has given them. Let God's name be

sanctified by them and not defiled" (H.H. Ben-Sasson, in:

Zion, 21 (1956), 205).

[The nobles found a network

of "private towns" - and Jews are assisting - Christian

resistance provokes new Jewish towns - first network of

Jewish towns]

The interests of the Jews and Polish magnates coincided and

complemented each other in one most important aspect of the

economic and social activity of the Polish-Lithuanian

nobility. On their huge estates the nobles began to establish

and encourage the development of new townships, creating a

network of "private towns". Because of the nature of their

relationship with their own peasant population they were keen

to attract settlers from afar [[from far away]], and Jews well

suited their plans. The tempo and scale of expansion were

great; in the grand duchy of Lithuania alone in the first half

of the 17th century between 770 and 900 such townships (miasteczki) existed (S.

Aleksandrowicz, in: Roczniki

dziejów spolecznych i gospadarczych, 27 (1965),

35-65). For their part, the Jews, who were hard pressed by the

enmity of the populace [[mob]] in the old royal cities, gladly

moved to places where they sometimes became the majority, in

some cases even the whole, of the population.

Since these were situated near the hinterland of agricultural

produce and potential customers, Jewish initiative and

innovation found a new outlet [[sector of activity]]. Through

charters granted by kings and magnates to communities and

settlers in these new towns, the real legal status of the Jews

gradually changed very much for the better. By the second half

of thee 17th century everywhere in Poland Jews had become part

of "the third estate" and in some places and in some respects

the only one.

Jews continued to hold customs stations openly in Lithuania,

in defiance of [[without considering]] the wishes of their

leaders in Poland (see Councils of the Lands). Many custom

station ledgers [[stoned monuments]] were written in Hebrew

script and contained Hebrew terms (see R. Mahler, in YIVO Historishe Shriftn

[[Yidd.: YIVO Historical Reports]], 2 (1937), 180-205).

Sometimes a Jew is found with a "sleeping partner", a Pole or

Armenian in whose name the customs lease has been taken out.

That some customs stations were in Jewish hands was also of

assistance to Jewish trade.

This complex structure of large-scale export and import trade,

the active and sometimes adventurous participation in the

colonization of the Ukraine and in the shaping of the "private

cities", in the fulfilling of what today we would call state

economic functions, created for the first time in the (col.

725)

history of Ashkenazi Jewry a broad base of population,

settlement distribution, and means of livelihood, which

provided changed conditions for the cultural and religious

life of Jews. Even after the destruction wrought by the

*Chmielnicki massacres enough remained to form the nucleus of

later Ashkenazi Jewry. The later style of life in the Jewish *shtetl [[Yidd.: little

town]] was based on achievements and progress made at this

time.

INTERNAL JEWISH LIFE.

[Jewish councils - fairs -

creativity]

The Councils of the Lands, the great superstructure [[head of

the structure]] of Jewish *autonomy, were an outgrowth

[[separate branch]] of such dynamics of economy and

settlement. Beginning with attempts at centralized leaderships

imposed from above, appointed by the king, they ended with a

central elected Jewish leadership. The aims, methods, and

institutions of this leadership were intertwined with the new

economic structure.

Great fairs - notably those of Lublin and Jaroslaw - since

they attracted the richest and most active element of the

Jewish population, also served as the meeting place of the

councils. Throughout its existence the Council of the Province

of Lithuania cooperated with its three (later five) leading

communities through a continuous correspondence with them and

between each of them and the smaller communities under its

authority.

Here the council was adapting the organizational methods of

large-scale trade to the leadership structure. The concern of

the councils with the new economic phenomena, like arenda, is

well known. They also concerned themselves with matters of

security and morals which arose from the thin spread of Jewish

families in Christian townships and villages.

On the whole, up to 1648 a sense of achievement and creativity

pervades their enterprises and thought. A preacher of that

time, Jedidiah b. Israel *Gottlieb, inveighed against a man's

gathering up riches for his children, using the argument of

the self-made man:

"The land is wide open, let them be mighty in it, settle and

trade in it, then they will not be sluggards, lazy workers,

children relying on their father's inheritance, but they

themselves will try ... to bring income to their homes, in

particular because every kind of riches coming through

inheritance does not stay in their hands ... easy come, easy

go ... through their laziness ... they have to be admonished

... to be mighty in the land through their trading: their

strength and might shall bring them riches" (Shir Yedidut

(Cracow, 1644), Zeidah la-Derekh, fol. 24a).

[Growing Jewish population -

influx of Jewish refugees]

This buoyancy [[holding force]] was based on a continuous

growth of population throughout the 16th and the first half of

the 17th centuries, due both to a steady natural increase

thanks to improving conditions of life and to immigration from

abroad resulting from persecution and expulsions (e.g., that

from Bohemia-Moravia for a short period in 1542). As noted,

the growth was most intensive in the eastern and southeastern

areas of Poland-Lithuania, and it was distributed through the

growing dispersion [[expansion]] of Jews in the "private

cities" and in the villages.

At the end of the 16th century, Great Poland and Masovia

(Mazowsze) contained 52 communities, Lesser Poland 41, and the

Ukraine, Volhynia, and Podolia about 80; around 1648, the

latter region had 115 communities. From about 100,000 persons

in 1578 the Jewish population had grown to approximately

300,000 around 1648. It is estimated that the Jews formed

about 2.5-3% of the entire population of Poland, but they

constituted between 10% an 15% of the urban population in

Poland and 20% of the same in Lithuania.

[Jewish economy and

difficulties: trials, depths and methods for a "good name

for credit"]

The dynamics of Jewish economic life are evident not only in

the variety and success of their activities, but also in

certain specific institutions and problems that reveal the

tension behind their strain for economic goals which tended to

entail [[to cause]] risks. By the end of the 16th century,

Jews were (col. 726)

borrowers rather than lenders. Seventeenth-century

anti-Semites - Miczyński and Mojecki - accused Jews of

borrowing beyond their means and deceiving Christian lenders.

From their accusations it is clear that much of this credit

was not in ready cash but in goods given to Jewish merchants

on credit. Borrowing was a real problem with which the Jewish

leadership was much concerned. Many ordinances of the Councils

of the Lands, of the provincial councils, and of single

communities are preoccupied with preventing and punishing

bankruptcy. Great efforts were devoted to prevent non-payment

of debts to Christians in particular. Young men who were

building up a family were especially suspected of reaching

beyond their means. These ordinances tell in their own way the

story of a burgeoning economy which is strained to dangerous

limits, inciting in particular the young and the daring. A

good name for credit was then a matter of life and death for

the Jewish merchant.

The great halakhist Solomon Luria was prepared to waive

[[renounce]] an ancient talmudic law in favor of the lender

because "now most of the living of the Jews is based on

credit; whereas most of those called merchants have little of

their own and what they have in their hands is really taken

from gentiles on credit for a fixed period - for they take

merchandise [on credit] till a certain date - it is not seemly

for a judge to sequester [[fix by law]] the property of a

merchant, for news of this may spread and he will lose the

source of his living and all his gentile creditors will come

on him together and he will be lost, God forbid, and merchants

will never trust him again.I myself have seen and heard about

many merchants - circumcised and uncircumcised - to whom,

because people said about them that they are a risk, much harm

was caused and they never again could stand at their posts" (Yam shel Shelomo, Bava Kamma,

ch. 1, para 20).

[Jews take credit with Jews -

and credit letters]

Because of the importance of credit the practice of a Jews

lending on interest to another Jew became widespread in

Poland-Lithuania despite the fact that it was contrary to

Jewish law (see *usury). This necessitated the creation

there of the legal fiction of hetter iskah, formulated by a synod of

rabbis and leaders under the chairmanship of Joshua b.

Alexander ha-Kohen *Falk in 1607. Widespread credit also led

to the use of letters of credit specific to the Jews of

Poland, the so-called *mamran

(Pol. membrana, membran): the Jew would sign on one

side of the paper and write on the other side "this letter of

credit obliges to signed overleaf for amount x to be paid on date y."

[Cultural life and reforms in

Poland-Lithuania in 16th and 17th century - spirits and

synagogues]

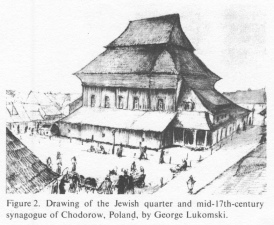

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. Drawing of the

Jewish quarter

and mid-17th-century synagogue of Chodorow, Poland, by

George Lukomski

Jewish cultural and social life flourished hand in hand with

the economic and demographic growth. In the 16th and early

17th centuries Poland-Lithuania became the main center of

Ashkenazi culture. Its *yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]]

were already famous at the beginning of the 16th century;

scholars like *Hayyim (Ḥayyim)b. Bezalel of Germany and David

b. Solomon *Gans of Prague were the pupils of *Shalom Shakhna

of Lublin and Moses Isserles of Cracow, respectively. Mordecai

b. Abraham *Jaffe; Abraham, Isaiah, and Jacob b. Abraham

*Horowitz; Eliezer b. Elijah *Ashkenazi; *Ephraim Solomon b.

Aaron Luntshits; and Solomon Luria were only a few of the

great luminaries of talmudic scholarship and moralistic

preaching in Poland-Lithuania of that time. Councils of the

Lands and community ordinances show in great detail of not the

reality at least the ideal of widespread Torah study supported

by the people in general.

This culture was fraught with great social and moral tensions.

Old Ashkenazi ascetic ideas did not sit too well on the

affluent and economically activist Polish-Lithuanian Jewish

society. Meetings with representatives of the Polish

*Reformation movement, in particular with groups and

representatives of the anti-trinitarian wing like Marcin

Czechowic or Szymon *Budny, led to disputations (col. 729)

and reciprocal influence. Outstanding in these contacts on the

Jewish side was the Karaite Isaac b. Abraham *Troki, whose Hizzuk Emunah (Ḥizzuk Emunah)

sums up the tensions in Jewish thought in the divided

Christian religious world of Poland-Lithuania. It was Moses

Isserles who formulated the Ashkenazi modifications and

additions to the code of the Sephardi Joseph Caro. Isaiah b.

Abraham ha-Levi *Horowitz summed up in his Shenei Luhot (Luḥot) ha-Berit

the moral and mystic teaching of the upper circles of

Ashkenazi Jewry. Yet his writings, and even more so the

writings of Isserles, give expression to the tensions and

compromises between rationalism and mysticism, between rich

and poor, between leadership and individual rights. To all

these tensions, Ephraim Solomon Luntshits gave sharp voice in

his eloquent sermons, standing always on the side of the poor

against the rich and warning consistently against the danger

of hypocrisy and self-righteousness. Fortifies and wooden

synagogues expressed the needs and the aesthetic sense of

Jewish society of that time.

In the old "royal cities" magnificent synagogue buildings were

erected as early as the 16th century (e.g. the Rema synagogue

at Cracow and the Great Synagogue of Lvov). Hebrew manuscripts

were brought from abroad and some of them illuminated

[[explained]] in Poland. Jewish printing developed early and

many beautiful works were published. Various sources describe

carnivallike Purim celebrations, and the fun, irony, and joy

of life expressed in now lost folk songs and popular games and

dramas.> (col. 730)

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

717-718

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

719-720

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

721-722

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

723-724

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

725-726

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

727-728

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

729-730

|

|

Č Ḥ

Ł ¦ Ṭ Ẓ Ż

ā ć č ẹ ȩ ę ḥ ī ł ń

ś ¨ ū ¸ ż ẓ

^

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. The fortress-type

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. Examples of Polish coins minted by Jews

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 727. Drawing of the Jewish quarter