Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Poland

04: 1919-1939

Borderlines and anti-Semitic state's policy of

"independent" anti-Semitic Poland in the name of

"nationalism" - numerus clausus, discriminations -

emigration wave - racist Zionists and anti-Zionists

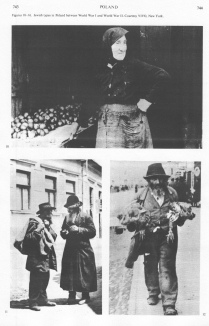

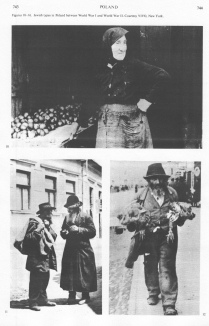

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 743-744. [[Jewish women at a market place selling

apples]]. Jewish type in Poland between World War I

and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 743-744. [[Jewish women at a market place selling

apples]]. Jewish type in Poland between World War I

and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne743-744-juedin-apfelverkaeuferin1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 743-744. [[Jewish

women at a market

place selling apples]]. Jewish type in Poland between

World War I

and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York

from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 13

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

[[The anti-Semitic Church is the main force of anti-Semitism -

the anti-Semitic Church as the main cause of anti-Semitism -

the anti-Semitic Church is never mentioned in the article]].

[Borderlines of "independent"

Poland since 1919]

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 719-720. Map of Poland

with the Provincial

distribution of Polish Jewry in towns and villages (1931).

Based on data from R. Mahler:

"Yehudei Polin bein Shetei Milhamot Olam", 1968

<INDEPENDENT POLAND.

As a result of World War I and the unexpected collapse of the

three partitioning powers, Poland was reconstituted as a

sovereign state. The final boundaries, not determined until

1921, represented something of a compromise between the

federalist dreams of Pilsudski and the more ethnic Polish

conception of R. *Dmowski. To Congress Poland, purely Polish

save for its large Jewish minority, were added Galicia,

Poznania, Pomerania, parts of Silesia, areas formerly part of

the Russian northwestern region, and the Ukrainian province of

Volhynia. The new state was approximately one-third

non-Polish, the important minorities being the Ukrainians,

Jews, Belorussians, and Germans.

[Polish nationalism with

anti-Jewish propaganda is going on - pogroms, e.g. Lvov 1918

and Vilna 1919]

The heritage of the war years was a particularly tragic one

for Polish Jewry. The rebirth of Poland, which many Jews had

hoped for, was accompanied by a campaign of terror directed by

the Poles (as by the invading Russian army in the early years

of the war) against them. The Jews too often found themselves

caught between opposing armies - between the Poles and the

Lithuanians in Vilna, between the Poles and the Ukrainians in

Lvov, and between the Poles and the Bolsheviks during the war

of 1920. And it is probably no accident that the two major

pogroms of this period, in Lvov in 1918 and in Vilna in 1919,

occurred in multi-national areas where national feelings

reached their greatest heights.

The triumph of Polish nationalism, far from leading to a

rapprochement between Jews and Poles, created a legacy of

bitterness which cast its shadow over the entire interwar

period. For the Poles the war years proved that the Jews were

"anti-Polish", "pro-Ukrainian", "pro-Bolshevik", etc. For the

Jews the independence of Poland was associated with pogroms.

[[Add to this the Russian markets were cut by the new

borderlines and the fight of the systems, and also

Austria-Hungary was parted into many national states which had

no intention to install a customs union. So the trade was

hindered by many borderlines, and the Russian market was lost

for the capitalist national states. By this the economies in

eastern Europe were never recovering and anti-Semitism had the

direct aim to eliminate the positions of the Jews, see Joint]].

[100,000 Jews killed in Ukrainian Polish war

1919-1921]

<The sense of disaster was already deeply embedded in the

consciousness of European Jews by the events which followed

right after the end of World War I. The far greater horrors

of the Nazi Holocaust have by now half obscured the murder

of about (col. 1054)

one hundred thousand Jews,

including women and children, in the Russian-Polish

borderland, where Ukrainian and counter-revolutionary

Russian army units systematically engaged in killing Jews in

the years 1919-21. (col. 1055)>

(from: Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Zionism, vol. 16, col.

1054-1055)

[Foundation of Poland with

protection of minorities in the constitution - hope for

autonomy]

The legal situation of the Jews in independent Poland was, on

the surface, excellent. The Treaty of *Versailles, concluded

between the victorious powers and the new states, included

provisions protecting the national rights of minorities; in

the Polish treaty Jews wee specifically promised their own

schools and the Polish state promised to respect the Jewish

sabbath. The Polish constitution, too, declared that non-Poles

would be allowed to foster [[use]] their national traditions,

and formally abolished all discrimination due to religious,

racial, or (col. 738)

national differences. The Jews were recognized by the state as

a nationality, something the [[racist]] Zionists and other

Jewish nationalists had long fought for.

[[This was the basic fault of world policy: Jews are not a

nationality, but they are a religion. When they were seen as a

nationality, anybody could say they would be a strange

nationality]].

There were great hopes [[of the racist Zionists]] that the

Jews would be allowed to develop their own national

institutions on the basis of national autonomy. These hopes

were not fulfilled.

[No acknowledgment for Jewish

schools - numerus clausus and discriminations against the

strange Jewish nation]

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 741-742. Heder (Ḥeder) [[Jewish religious school to

age of 13]] c. 1930. Courtesy YIVO, New York. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

741-742. Heder (Ḥeder) [[Jewish religious school to age

of 13]] c. 1930. Courtesy YIVO, New York.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne741-742-heder-schule1930-35pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 741-742. Heder (Ḥeder)

[[Jewish religious school to age of 13]] c. 1930. Courtesy

YIVO, New York.

The two cornerstones of Jewish autonomy - the school and the kehillah [[congregation]]

(see *Community) - were not allowed to develop freely. The

state steadfastly refused to support Jewish schools, save for

[[with the exception of]] a relatively small number of

elementary schools closed on Saturday which possessed little

Jewish content. The Hebrew-language *Tarbut [[cultural]]

schools, along with the Yiddish-language CYSHO (see

*Education) network, were entirely dependent on Jewish

support, and the diplomas issued by the Jewish high schools

were not recognized by the Ministry of Education. The Jewish

schools were successful as pedagogical institutions, but the

absence of state support made it impossible for them to lay

the foundation for a thriving [[growing]] Jewish national

cultural life in Poland.

As for the kehillah

[[congregation]], projected by Jewish nationalists as the

organ of Jewish national autonomy on the local level, it was

kept in tight check by the government. While elections to the

kehillah were made

democratic, enabling all Jewish parties to participate on a

basis of equality, the government constantly intervened to

support its own candidates, usually those of the orthodox

*Agudat Israel. By the same token the government controlled

the budgets of the kehillot

[[congregations]]. These institutions remained essentially

what they had been in the preceding century, concerned above

all with the religious life of the community.

Far from barring discrimination against non-Poles, the policy

of the interwar Polish state was to promote the ethnic Polish

element at the expense of the national minorities, and above

all at the expense of the Jews, who were more vulnerable than

the essentially peasant Slav groups. The tradition of numerus clausus was

continued at the secondary school and university level,

efforts were made to deprive [[rob]] the "Litvaks" of Polish

citizenship, local authorities attempted to curb the use of

Yiddish and Hebrew at public meetings, and the Polish

electoral system clearly discriminated against all the

minorities.

All Jewish activities leading toward the advancement of Jewish

national life in Poland were combated;

[[The basic fault that to be Jewish is not a nation but is a religion is never

mentioned in Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

the government favored [[racist]] Zionism only insofar as it

preached emigration to Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of

Israel]], and in domestic politics tended to support the

traditional Orthodoxy of Agudat Israel. Worst of all was the

economic policy of the state.

[[Emigration numbers are missing in this article]].

[Numbers]

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 744 [[Jew with chicken]]. Jewish type in Poland

between World War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO,

New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

744 [[Jew with chicken]]. Jewish type in Poland between

World War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne744-jude-m-poulets1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 744 [[Jew with

chicken]]. Jewish type in

Poland between World War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO,

New York

According to official statistics, most likely too low, Jews

made up 10.5% of the Polish population in 1921. The density of

their urban settlement was related to the general development

of the area. In less developed regions, such as East Galicia,

Lithuania, and Volhynia, the Jewish percentage in the cities

was very high, while in more developed [[industrialized and

destroyed]] areas, such as Central Poland (the old Congress

Poland), the existence of a strong native bourgeoisie caused

the Jewish percentage to be lower.

As for the Jewish village population, it too was higher in

backward areas, since the number of cities was naturally less.

There were, therefore, substantial Jewish village populations

in Galicia and Lithuania but not in the old Congress Poland

(with the exception of Lublin province, economically backward

in comparison with the other provinces of the region). The

most striking development in the demography of Polish Jewry

between the wars is the marked loss of ground in the cities

[[probably because of emigration by Danzig]]. Table 6

illustrates this point. (col. 739)

Table 6. Decrease in the Percentage of the

Jews in the Total Population in the Cities of

Poland in the Interwar Period.

|

City

|

Percentage

of

Jews in 1921

|

in

1931

|

Warsaw

|

33.1

|

30.1

|

Lvov

|

35.0

|

31.9

|

Vilna

|

36.1

|

28.2

|

Bialystok

|

51.6

|

43.0

|

Grodno

|

53.9

|

42.6

|

Brest-Litovsk

|

53.1

|

44.3

|

Pinsk

|

74.7

|

63.4

|

| from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971,

vol. 13, col. 740 |

[Colonization with Poles and

Jewish emigration wave]

Among the factors contributing to this decline was the Polish

government's "colonization" policy in non-Polish areas, its

changing of city lines to diminish the Jewish proportion, and

Jewish emigration (though with America's gates shut [[since

1924]] this last factor was [[concerning the criminal "USA"]]

not very significant).

[[The racist criminal "USA" restricted Jewish immigration in

1924. But it can be admitted that Jewish emigration was going

on under other nationality quotas by changing nationality with

forged documents which were easy to have by Jewish emigration

organizations in Poland. Mostly the young generation

emigrated]].

Another (col. 739)

major cause would appear to be the low Jewish natural

increase, caused by a low birth rate. [[This lower birthrate

was caused because of the high emigration of the young

generation. This is an indirect proof that emigration was

always going on and on also after 1924]].

Table 7 presents the natural increase of four major religious

groups in interwar Poland:

Table 7. The Natural Increase of Four Major

Religious Groups in Poland in the Interwar Period

[1920-1939?]

|

Religion

|

Natural

increase

[[in percent]]

|

Roman Catholicxxxxxxxxx

|

13.1%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

|

Greek Catholic

|

12.5%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

Greek Orthodox

|

16.7%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

Jewish

|

9.5%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

| from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971,

vol. 13, col. 740 |

Thus the process of Jewish population expansion in Poland

ended, itself the victim of urbanization (which led, in turn,

to a low birth rate).

[[This urbanization is only one factor. Emigration of the

young generation is not mentioned, but is mentioned in many

other articles of the Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

If the cities were Judaized during the 19th century, they were

Polonized in the 1920s and 1930s.

[Professions - Polish system

controlling all economy - systematic discrimination of the

Jews since 1919]

The demographic decline of Polish Jewry was paralleled by a

more serious economic decline. On the whole, Polish Jews

between the wars continued to work at the same trades as their

19th-century predecessors and the tendency toward

"productivization" also continued. The vast majority of those

engaged in industry were artisans, among whom tailors

predominated; those working in commerce were, above all,

shopkeepers.

What distinguished the interwar years from the prewar era was

the anti-Semitic policy of the Polish state, which Jewish

leaders accused of leading to the economic "extermination" of

Polish Jewry. Jews were not employed in the civil service,

there were very few Jewish teachers in the public schools,

practically no Jewish railroad workers, no Jews employed in

state-controlled banks, and no Jewish workers in state-run

monopolies (such as the tobacco industry). In a period

characterized by economic étatism

[[a sort of absolutism]], when the state took a commanding

role in economic life, such official discrimination became

disastrous. There was no branch of the economy where the state

did not reach; it licensed artisans, controlled the banking

system, and controlled foreign trade, all to the detriment of

the Jewish element.

Its tax system discriminated against the urban population, and

its support of peasant cooperatives struck at the Jewish

middleman. Such specific legislation as the law compelling all

citizens to rest on Sunday helped to ruin Jewish commerce by

forcing the shopkeeper to rest for two days and to lose the

traditionally lucrative Sunday trade.

More natural forces were also at work in the decline of the

Jews' economic condition, e.g., the continued development of a

native middle class, sponsored by the government but not

created by it. According to research carried out by the *YIVO

in 113 Polish cities between 1937 and 1938, the number of

Jewish-owned stores declined by one, while the number of

stores owned by Christians increased by 591. In the western

Bialystok province, to cite another example, the number of the

Jewish -owned stores declined between 1932 and 1937 from 663

to 563, while (col. 740)

the number of Christian-owned stores rose from 58 to 310.

These figures reflect both the impact of anti-Semitism (in the

late 1930s the anti-Jewish boycott became effective) and the

impact of the developing Polish (and Ukrainian) middle class.

[[see also: *Boycott,

anti-Jewish]]

[[Whole eastern Europe with it's new borderlines and at the

cut borderline to Communist Russia wanted to get rid of the

Jews and were performing a heavy discrimination of the Jews.

Details about the anti-Semitic Polish policy since 1919 can be

seen in: Yehuda Bauer: Joint

(policy since 1919) and a whole

chapter

about anti-Semitic Poland (1919-1938)]

The Jews' economic collapse in the interwar period bears

witness to the disaster, from the Jewish point of view,

inherent [[existing in the center]] in the rise of exclusive

nation-states on the ruins of the old multinational empires.

Jews were employed in the old Austrian public schools of

Galicia, but not in the Polish state-operated schools. They

worked as clerks in the railroad offices of Austrian Galicia,

but not in Poland. Thousands of Jewish cigarette factory

workers in the old Russian Empire were dismissed when the

Polish state took over the tobacco monopoly. It also

demonstrates the extremely vulnerable position of the Jews

vis-à-vis the other Polish minorities, largely peasant nations

which did not compete with the Polish element. The urban

Jewish population found itself in a situation in which the

traditional small businessman was being squeezed out [[by

special taxes]], while the policy of the state also ruined the

wealthy Jewish merchant and industrialist. This was then the

end of a process already discernible [[developing]] in the

late 19th century, immeasurably [[without any limits]] speeded

up by a state which wanted to see all key economic positions

in the hands of "loyal" elements, i.e., Poles.

[[The Jewish aid organizations were organizing support by loan

kassas, and by this help it was possible that Polish Jewry

existed until 1939, see Yehuda Bauer: Joint]].

[Racist Zionism is dominating

Jewish life in Poland with over 50%]

What was the Jews' political response to this situation? In

the beginning of the interwar period the *General ZIonists

emerged as the strongest force within the Jewish community,

thus reflecting the general trend in eastern Europe toward

nationalism and, in the Jewish context, reflecting the impact

of the terrible war years. In the 1919 Sejm elections the list

of the Temporary Jewish National Council, dominated by

[[racist]] General Zionists, received more than 50% of those

votes cast for Jewish parties. In 1922, when Jewish

representation in the Sejm reached its peak, the percentage of

[[racist]] General Zionists (together with the *Mizrachi)

among the Jewish deputies was again over 50% (28 out of 46).

The Jewish Club (Kolo) in the Sejm, which claimed to speak for

all Polish Jewry, was naturally dominated by [[racist]]

General Zionists, who with considerable justice regarded

themselves as the legitimate spokesmen of the community.

[Fight of different racist

Zionist "schools": Gruenbaum and Reich arguing about tactics

against anti-Semites - split of racist Warsaw Zionists in

"radical Zionists" and "General Zionists"]

[[Racist]] General Zionism in Poland was divided into two

schools, that of "Warsaw-St. Petersburg" and that of

"Lvov-Cracow-Vienna". The former came of age in the

revolutionary atmosphere of the czarist regime and

consequently tended to be more extreme in its demands than the

Galicians, who had learned their politics in the Austrian

Reichsrat. The clash between Yizhak (Yiẓḥak) *Gruenbaum,

leader of the Warsaw faction, and Leon *Reich of Lvov was well

expressed in the negotiations carried on between the Jewish

Sejm Club and the Polish government in 1925. Gruenbaum,

rejecting negotiations with anti-Semites and offering instead

the idea of a national minorities bloc, found himself

outnumbered in the club by adherents of Reich's position,

namely that negotiations should be carried on in order to halt

the deterioration of the Jewish position. In the end neither

Gruenbaum's minorities bloc nor Reich's negotiations caused

any improvements; the tragedy of Jewish politics in Poland was

that the government would not make concessions to the Jews so

long as it was not forced to do so, and the Jews, representing

only 10% of the population, could find no allies.

All [[racist]] General Zionists agreed on the importance of

"work in the Diaspora", though Gruenbaum, the central figure

in this work, was castigated [[sharply criticized]] by

Palestinian pioneers as the apostle of "Sejm-Zionismus". They

did not agree, however, on various aspects of [[racist]]

Zionist policy; the efforts to broaden the *Jewish Agency and

the nature of the Fourth *Aliyah (col. 749)

caused a split within the [[racist]] Warsaw Zionists,

Gruenbaum leading the attack on Chaim *Weizmann and upholding

the young pioneering emigration while his opponents defended

the "bourgeois" aliyah

and Weizmann's conciliatory tactics toward non-Zionist Jewry.

Gruenbaum's faction, Al ha-Mishmar ("On Guard"), remained in

the minority throughout the 1920s, but the so-called

[[racist]] "radical Zionists returned to power in the 1930s

following the failure of the Agency reform, the crisis in the

Fourth Aliyah, and the stiffening of the British line in

Palestine. The [[racist]] General Zionists, of course, did not

monopolize Jewish political life in interwar Poland. On the

right, non-Zionist Orthodoxy was represented by the Agudat

Israel, which succeeded in dominating the Jewish kehillot

[[congregation]], but its generally good relations with the

government did not stem the anti-Semitic tide.

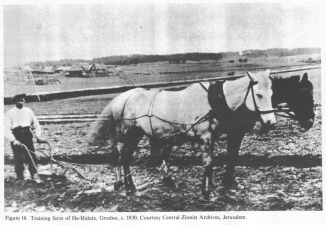

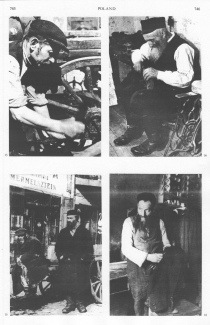

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 747-748. Training farm

of He-Halutz,

Grodno, c. 1930. Courtesy Central Zionist Archives,

Jerusalem

[Anti-Zionist Socialist party

Bund - Yiddish culture]

On the left the dominant Jewish party was the Bund, which had

disappeared in Russia but survived to play its last historic

role as the most important representative of the Jewish

proletariat in Poland. The Bund, like Gruenbaum's [[racist]]

Zionist faction, also recognized the need for allies in the

struggle for a just society in which, its leaders hoped, Jews

would be able to promote their Yiddish-based culture. Such

allies were sought on the Polish left rather than among the

disaffected minorities, but the Polish Socialist Party (PPS),

for reasons of its own, had no desire to be branded

[[exposed]] pro-Jewish. Unable to cerate a bloc with the

Polish proletariat, the Bund devoted itself to promoting the

interests of the Jewish working class and took a great

interest in the development of Yiddish culture. Despite the

fact that this party, too, was split into factions (the split

turned chiefly on different attitudes toward the international

Socialist movement), it was to grow in influence.

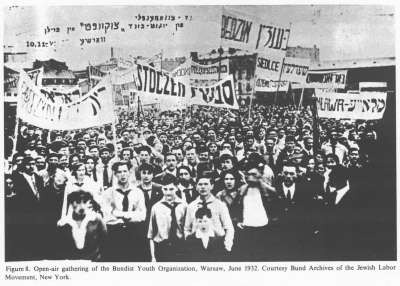

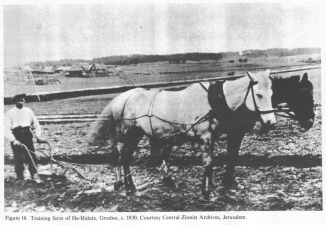

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 741-742. Open-air

gathering of the Bundist Youth Organization,

Warsaw, June 1932. Courtesy Bund Archives of the Jewish

Labor Movement, New York.

[Racist Socialist Zionist

parties]

Sharing the left with the Bund, though overshadowed by it in

terms of worker allegiance, were the various [[racist]]

Socialist Zionist parties, ranging from the non-Marxist

*Hitahadut (Hitaḥadut) to the leftist *Po'alei Zion (the

Po'alei Zion movement had split into right and left factions

in 1920; in Poland the left was dominant, at least in the

1920s). The moderate [[racist]] Socialist Zionists were

concerned mainly with the pioneering emigration to Erez Israel

(Ereẓ Israel), while the Left Po'alei Zion steered a perilous

course of non-affiliation either with the Zionist organization

or with the Socialist International. Its ideological

difficulties with the competition of the anti-Zionist Bund

(which went so far as to brand Zionism as an ally of Polish

anti-Semitism [[which in reality probably was because

anti-Semitism forced for emigration]]) sentenced the Left

P'alei Zion to a relatively minor role among the Jewish

proletariat, though its influence among the intelligentsia was

by no means negligible.

[Racist Orthodox Zionists:

Mizrachi - cultural *Folkspartei]

Two other Jewish parties deserve mention. The Polish Mizrachi,

representing the [[racist]] Zionist Orthodox population,

enjoyed a very large following (eight of its representatives

sat in the Sejm in 1922). The Mizrachi usually cooperated with

the [[racist]] General Zionists, though its particular mission

was to safeguard the religious interests of its followers in

Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) [[Land of Israel]] and in the

Diaspora.

The *Folkspartei, on the other hand, never managed to make an

impression on political life in Poland, though its

intellectual leadership was extremely influential on the

cultural scene. Both anti-Zionist and anti-Socialist, it could

never attain a mass following.

[Radicalization of racist

Zionism: large emigration wave in the mid-1930s - and Bund

coming up]

The economic collapse of Polish Jewry, together with the rise

of virulent anti-Semitism, led to the radicalization of Jewish

politics in Poland. Extreme solutions to the Jewish question

gained more adherents as the parliamentary approach clearly

failed to lead anywhere; hence the growth of the pioneering

[[racist]] Zionist movements - *He-Haluz (He-Ḥaluẓ), He-Haluz

ha-Za'ir (He-Ḥaluẓ ha-Ẓa'ir), *Ha-Shomer ha-Za'ir (Ha-Shomer

ha-Ẓa'ir), and others - resulting in the large-scale emigration to Erez

Israel (Ereẓ Israel) in the mid-1930s, and also the

inroads of Communism among the Jewish youth.

Another symptom of this radicalization (col. 750)

was the great success of the Bund in the 1930s; by the late

1930s the Bund had "conquered" a number of major kehillot

[[congregations]] and was probably justified in considering

itself the strongest of all Jewish parties. This spectacular

success did not occur as a result of any apparent party

success, since the efforts to improve the lot of the Jewish

proletariat and to forge a bloc with the Polish left had

failed. Rather, the Bund's success may be attributed to the

rising protest vote against attempts to mollify the regime and

in favor of an honorable defense, no matter how unavailing, of

Jewish interests.

[Changes within the racist

Zionist parties in Poland in the 1930s: Socialists and

Communists coming up]

Within the [[racist]] Zionist movement the process of

radicalization was very clearly illustrated by the decline of

the [[racist]] General Zionists and the rise of the Socialists

and the Revisionists. In the elections to the 18th [[racist]]

*Zionist Congress, held in 1933, the [[racist]] labor Zionists

of Central Poland received 38 mandates and the [[racist]]

General Zionists only 12. The same congress seated 20 Polish

Revisionists, whose growing strength faithfully reflected the

mood of Polish Jewry. In short, a transformation may be

discerned of what might be called the politics of hope into

the politics of despair. The slogans of haluziyyut (ḥaluẓiyyut)

("pioneering"), evacuation, and Communist ideology became more

and more palatable as the old hopes for Jewish autonomy and

the peaceful advancement of Jewish life in a democratic Poland

disappeared.

[Pogroms and boycotts since

1933]

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Poland, vol. 13, col. 743. [[Two Jews speaking in the

street]]. Jewish types in Poland between World War I and

World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

743. [[Two Jews speaking in the street]]. Jewish types

in Poland between World War I and World War II. Courtesy

YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne743-2-juden1919-1939-36pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 743. [[Two Jews

speaking in the street]].

Jewish types in Poland between World War I and World War II.

Courtesy YIVO, New York

[[Pogroms and boycotts were traditional in Poland since 1919

already. The Situation since 1933 did not change much]].

By the late 1930s the handwriting was clearly on the wall for

Polish Jewry, though no one could foresee the horrors to come.

The rise of Hitler in Germany was paralleled by the appearance

of Fascist and semi-Fascist regimes in eastern Europe, not

excepting Poland. A new wave of pogroms erupted along with a

renewed anti-Jewish boycott, condoned [[accepted]] by the

authorities. The Jewish parties were helpless in the face of

this onslaught [[storm]], especially as the disturbances in

Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) resulted in a drastic decline in aliyah.

[[Emigration with changing names, changing nationality with

forged documents is not mentioned in this article but forged

documents could easy be provided by Jewish emigration

organizations. It can be admitted that emigration movement

continued under other nation quotas to overseas and to the

racist criminal "USA"]].

[Summary 1772-1939]

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 747-748. Summer camp, 1925 [[probably organized

by the Joint]]. Courtesy Joint Distribution Committee,

New York. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

747-748. Summer camp, 1925 [[probably organized by the

Joint]]. Courtesy Joint Distribution Committee, New

York.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne747-748-Joint-sommerlager1925-34pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 747-748. Summer camp,

1925 [[probably organized by the Joint,

see: Yehuda Bauer:

Joint]].

Courtesy

Joint Distribution Committee, New York.

The political dilemma of Polish Jewry remained unresolved;

finding no allies, Jewish parties could do little to influence

the course of events. It should be recalled, however, that the

role of these parties was greater than the narrow word

"political" implies. Their work in raising the educational

standards of Polish Jewry was remarkable, and the Jewish youth

movements were able to supply to the new generation of Polish

Jews a sense of purpose and a certain vision of a brighter

future.

Polish Jewish history from 1772 to 1939, reveals an obvious

continuity. The Jews remained a basically urban element in a

largely peasant country, a distinct economic group, a minority

whose faith, language, and customs differed sharply from those

of the majority. All attempts to break down this

distinctiveness failed, and the Jews naturally suffered for

their obvious strangeness. A thin layer of assimilated, or

quasi-assimilated, Jews subsisted throughout the entire

period, but the masses were relatively unaffected by the

Polish orientation.

In the end all suffered equally from Polish anti-Semitism.

There were also several basic discontinuities. The rise of an

exclusively national Polish state in 1918 was a turning point

in the deterioration of the Jews' position, though the signs

of this deterioration were already visible in the late 19th

century. The rise of a native middle class, encouraged by

state policy, put an end to the Jews' domination of trade and

forced them into crafts and industry, resulting in the

emergence of a large Jewish proletariat.

Politically speaking perhaps the greatest change was the

triumph within the community of Jewish nationalism, whether

[[racist]] Zionist, [[Socialist anti-Zionist party]] Bundist,

or [[Capitalist anti-Zionist]] Folkist, at the expense of the

traditional assimilationist or Orthodox leadership. In this

sense Polish Jewry followed the same course of development as

the other peoples of eastern Europe. It was a tragic paradox

that these nationalist parties, which extolled the principle

of activism and denounced the (col. 751)

passivity of the Jewish past, also depended for their

effectiveness on outside forces. Neither the Polish government

nor the Polish left proved to be possible allies in the

struggle for survival.

[E.ME.]> (col. 752)

[[It seems to be strange that the work and the stock exchange

crash of 1929 is never mentioned in the article, see e.g.: Joint,

and the help and the donations of the Jewish aid organizations

not either, see: Joint.

Add to this the decisive role of the anti-Semitic "Christian"

Church is not mentioned either, see: Joint.

And there is never indicated how many Jews could emigrate, and

also general Jewish population figures for 1919-1939 - which

would be very important for the number of Jews of 1939 - are

only indicated for 1931, and about the emigration of 1931-1939

are no figures indicated]].

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

737-738 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

739-740

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

741-742

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

743-744

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

745-746

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

747-748

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

749-750

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

751-752 |

Č Ḥ

Ł ¦ Ṭ Ẓ Ż

ā ć č ẹ ȩ ę ḥ ī ł ń

ś ¨ ū ¸ ż ẓ

^

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 743-744. [[Jewish women at a market

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 719-720. Map of Poland with the Provincial

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 741-742. Heder (Ḥeder)

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 744 [[Jew with chicken]]. Jewish type in

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 747-748. Training farm of He-Halutz,

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 741-742. Open-air gathering of the Bundist Youth Organization,

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 743. [[Two Jews speaking in the street]].

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 747-748. Summer camp, 1925 [[probably organized by the Joint,

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 743-744. [[Jewish women at a market place selling

apples]]. Jewish type in Poland between World War I

and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 743-744. [[Jewish women at a market place selling

apples]]. Jewish type in Poland between World War I

and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne743-744-juedin-apfelverkaeuferin1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 741-742. Heder (Ḥeder) [[Jewish religious school to

age of 13]] c. 1930. Courtesy YIVO, New York. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

741-742. Heder (Ḥeder) [[Jewish religious school to age

of 13]] c. 1930. Courtesy YIVO, New York.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne741-742-heder-schule1930-35pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 744 [[Jew with chicken]]. Jewish type in Poland

between World War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO,

New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

744 [[Jew with chicken]]. Jewish type in Poland between

World War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne744-jude-m-poulets1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

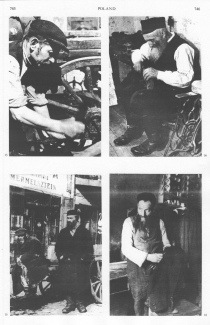

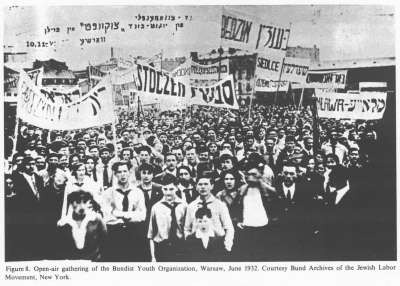

![Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 745.

[[Jewish artisan]]. Jewish types in Poland

between World War In and World War II. Courtesy

YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 745. [[Jewish artisan]]. Jewish types

in Poland between World War In and World War II.

Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne745-jude-schmied1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 746.

[[Jewish shoemaker]]. Jewish types in Poland

between World War In and World War II. Courtesy

YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 746. [[Jewish shoemaker]]. Jewish types

in Poland between World War In and World War II.

Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne746-jude-schuhmacher1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 745.

[[Jewish transport]]. Jewish types in Poland

between World War In and World War II. Courtesy

YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 745. [[Jewish transport]]. Jewish types

in Poland between World War In and World War II.

Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne745-jude-transporteur1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland,

vol. 13, col. 745. [[Seems to be a Jewish

tailor]]. Jewish types in Poland between World

War In and World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New

York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 745. [[Seems to be a Jewish tailor]].

Jewish types in Poland between World War In and

World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne746-jude-schneider1919-1939-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Poland, vol. 13, col. 743. [[Two Jews speaking in the

street]]. Jewish types in Poland between World War I and

World War II. Courtesy YIVO, New York Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

743. [[Two Jews speaking in the street]]. Jewish types

in Poland between World War I and World War II. Courtesy

YIVO, New York](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne743-2-juden1919-1939-36pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol.

13, col. 747-748. Summer camp, 1925 [[probably organized

by the Joint]]. Courtesy Joint Distribution Committee,

New York. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

747-748. Summer camp, 1925 [[probably organized by the

Joint]]. Courtesy Joint Distribution Committee, New

York.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne747-748-Joint-sommerlager1925-34pr.jpg)