Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Warsaw

02: Holocaust and post-war times

Discriminations - Warsaw ghetto

- underground work - underground institutions and

secret Jewish religious services - deportations -

armed resistance and Warsaw ghetto uprising 1943 -

Warsaw uprising 1944 - Jews coming back from central

Russia 1945-1946 - emigration waves 1946-1970

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

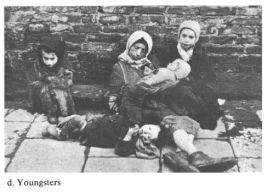

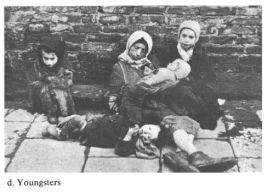

Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Youngsters in the streets of

Warsaw ghetto.

Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto by a German war

correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

from: Warsaw; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 16

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2020)

<Holocaust Period.

[[The battle of Warsaw and the flight movements to eastern

Poland are missing in the article]].

[German discriminating law

against Jewry in Warsaw since October 1939]

When German forces entered the city on Sept. 29, 1939, there

were 393,950 Jews, comprising approximately one-third of the

city's population, living in Warsaw.

Between October 1939 and January 1940 the German occupation

authorities issued a series of anti-Jewish measures against

the Jewish population. These measured included

-- the introduction of forced labor;

-- the order that every Jew should wear a white armband with a

blue star of David [["Jewish Armband"]], and the special

marking of Jewish-owned businesses;

-- confiscation of Jewish real estate and other property;

-- and a prohibition against Jews using the railway and other

public transportation.

THE GHETTO. [340 hectares -

special permits - Jewish Council - German commissioner

Auerswald and bridge over Chlodna Street since 1941]

|

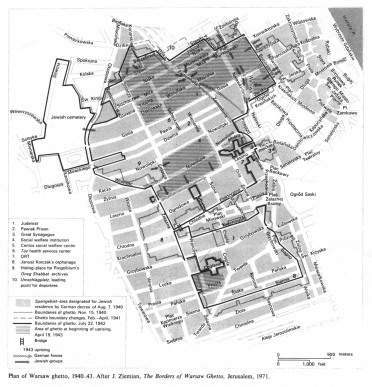

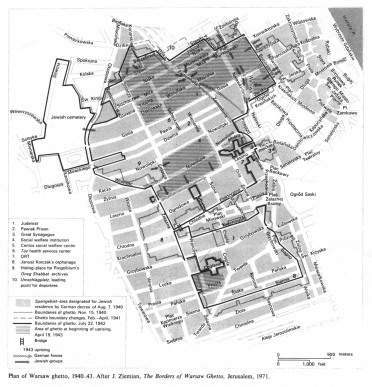

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 347-348. Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 347-348.

Plan (map) of Warsaw ghetto, 1940-43. After J.

Ziemian: "The Borders of Warsaw Ghetto", Jerusalem,

1971.

There are indicated: 1. the office of the Jewish

Council (Judenrat); 2. Pawiak Prison; 3. Great

Synagogue; 4. Social welfare institution; 5. Centos

social welfare center; 6. Toz health services

center; 7. ORT office; 8. Janusz Korczak's

orphanage; 9. Hiding-place for Ringelblum's archives

"Oneg Shabbat"; 10. assembly

point ("Umschlagplatz") for deportees.

Add to this are indicated: in gray: area

designated for Jewish residence by German

decree of 7 August 1940;

gray line: boundaries of the ghetto of 15

November 1940; in gray little lines:

ghetto boundary changes from Feb. to April

1941;

in black lines: the boundaries of the

ghetto on 22 July 1942;

in gray lines: the area of the ghetto at

the beginning of the uprising on 19 April

1943; also the bridge over Chlodna street

is indicated, and with arrows are

indicated the movements of the troops

during the uprising of 1943. |

In April 1940 the Germans began constructing a wall to enclose

the future Warsaw ghetto. On October 2, the Germans

established a ghetto for all Warsaw Jews and Jewish refugees

from the provinces. Withing six weeks all Jews or persons of

Jewish origin had to move into the ghetto, while all "Aryans"

residing in the assigned area had to leave.

The ghetto originally covered 340 hectares (approximately 840

acres), including the Jewish cemetery. As this area was

gradually reduced by the Germans, the walls were moved, and

the number of gates changed. [[...]]

The gates were guarded by German and Polish police from the

outside and by the Jewish militia (Ordnungsdienst) from the inside and only

those with a special permit could enter or leave the ghetto.

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Jewish police

force. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

by a German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

In the beginning, the Warsaw city hall, German political

authorities, and a special office, the "Transferstelle",

responsible for financial affairs, dealt with the ghetto's

administration. [[...]]

The head of the Jewish community council was Adam *Czerniakow,

an engineer who had been appointed by the mayor of Warsaw

during the siege (Sept. 23, 1939). By order of Hans Frank

(Sept. 28, 1939), a *Judenrat was created, consisting of 24

members, and presided over by Czerniakow. Czerniakow carried

out his functions for the general good under trying

conditions, often interceding with the German authorities to

ameliorate the repressive regulations. He tirelessly supported

social and cultural institutions in the ghetto and provided

relief wherever possible. [[...]]

From April 1941 a German commissioner, Heinz Auerswald, was

appointed over the ghetto. [[...]]

In the autumn of 1941 the ghetto was divided into two parts,

joined by a bridge over Chlodna Street. [[...]]

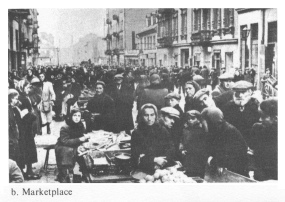

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Market place of Warsaw

ghetto. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

by a German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

Originally some 400,000 Jews were crowded into the area of the

ghetto. The reductions in its size necessitated internal

shifting and further overcrowding, so that thousands of

families were often left without shelter. The situation was

further aggravated when some 72,000 Jews from the Warsaw

district (see Poland) were transferred to the ghetto, bringing

the total number of refugees to 150,000 (April 1941). The

average number of persons per room was 13, while thousands

remained homeless. The ghetto population during various

periods prior to July 1942 is estimated to have been between

400,000 and 500,000.

[Confiscations by the

Transferstelle - food discrimination - working conditions -

heating question - mass death in the ghetto - flight and

Nazi collaboration of the Polish police - deportation to

forced labor camps - >100,000 victims in the Warsaw

ghetto estimated]

The confiscation and plunder of Jewish property was conducted

by the "Transferstelle". In January 1942, Jewish goods valued

at 3,736,000 zlotys ($947,600); in March - 6,0445,000 zlotys

($1,209,000); and in April - 6,893,000 zlotys ($1,378,000).

The ghetto population received a food allocation amounting to

184 calories per capita a day, while the Poles received 634,

and the Germans 2,310. The price per large calory was 5.9

zlotys (about $1) for Jews, 2.6 zlotys (50 cents) for Poles,

and 0.3 zlotys ($.06) for Germans. The average allocation per

person in the ghetto was four pounds of bread and a half pound

of sugar a month. The dough was mixed with sawdust [[wooden

dust]] and potato peels.

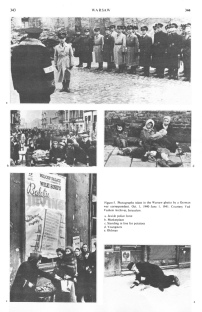

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16,

col. 344. Standing in line for potatoes in the Warsaw

ghetto. [[In the background can be seen a poster for a

ballet performance]]. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

by a German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1,

1941. Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

344. Standing in line for potatoes in the Warsaw ghetto.

[[In the background can be seen a poster for a ballet

performance]]. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto by a

German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Warschau-d/EncJud_Warsaw-band16-kolonne343-schlangestehen-f-kartoffeln-45pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Standing in line

for potatoes in the Warsaw ghetto.

[[In the background can be seen a poster for a ballet

performance]]. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto by a

German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

The ghetto suffered from mass unemployment. In June 1941,

27,000 Jews were active in their professions, while 60% of the

Jewish population had no income at all. A small number of Jews

who had their own tools and machines found employment in

factories taken over by Germans.

Wages were minimal. For 10-12 hours of of strenuous labor, a

skilled worker earned 2 1/-5 zlotys ($0.50-1.00) daily.

There was an acute shortage of fuel to heat the houses. In the

winter of 1941-42, 718 out of the 780 apartments investigated

had no heat.

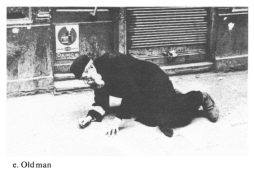

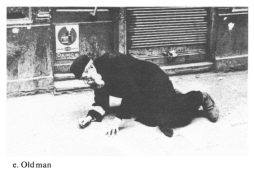

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Old man. Photo

taken in the Warsaw ghetto

by a German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

These conditions led to epidemics, especially typhoid. The

streets were strewn with corpses due to starvation and

disease. Bands of children roamed the streets in search of

food. A few women and children occasionally slipped across to

the "Aryan" side, in an attempt to find food or shelter. The

[[collaborating, anti-Semitic]] Polish police usually seized

them and turned them over to the Germans. In October 1941 the

authorities declared that leaving the ghetto without

permission was punishable by death. (col. 342)

From time to time the authorities rounded up able-bodied

people in the streets and sent them to slave labor camps. In

April 1941 some 25,000 Jews from the Warsaw ghetto lived in

the camps under conditions that rapidly decimated their

numbers. After the outbreak of the German-Soviet War (June

1941), many of the inmates in the camps were executed.

It is estimated that by the summer of 1942, over 100,000 Jews

died in the ghetto proper.

[Underground work in the

ghetto - smuggling - ghetto institutions and aid

organizations - "soap kitchens" and "trade courses" -

Ringelblum archives - secret synagogues]

Nevertheless, the morale of the ghetto inhabitants was not

broken, and continual efforts were made to overcome the German

decrees and organize relief. Illegal workshops were gradually

established for manufacturing goods to be smuggled out and

sold on the "Aryan" side. These included leather products,

metals, furniture, textiles, clothing, and millinery. At the

same time raw materials were smuggled in. In this way

thousands of families were sustained.

the smuggling of foodstuffs into the ghetto, carried out by

Jewish children, was especially intensive. In December 1941

the official import of foodstuffs and materials into the

ghetto was valued at 2,000,000 zlotys ($400,000) while illegal

imports totaled 80,000,000 zlotys ($16,000,000). Social

welfare institutions were active (col. 347)

to combat hunger and disease. The *Centos for social welfare,

the *Toz for health services, and other organizations

re-formed and established hospitals, public kitchens (daily

providing over 100,000 soup rations), orphanages, refugee

centers, and recreation facilities. In each block of houses a

committee for charitable work functioned and also engaged in

cultural and educational activities, such as reading groups,

lectures, and musical evenings.

A network of schools, both religious and secular, as well as

trade schools functioned in the ghetto. Some of these schools

were illegal and could operate only under the guise of soup

kitchens. Similarly, medical, technical, and scientific

training was given under the guise of trade courses.

By the end of 1940 the Jewish historian, Emmanuel *Ringelblum,

established a secret historical and literary society under the

code name of Oneg Shabbat.

This group set up secret archives on the life and martyrdom of

the Polish Jews under the Nazis. These archives, which were

hidden in several places, were discovered after the war.

Despite the closing down of all synagogues and the prohibition

against public worship, clandestine services were held,

especially on holidays. Yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]]

secretly functioned. The zaddikim

(ẓaddikim) [[ultra-radical Jews]] of *Aleksandrow

(col. 349)

and *Ciechanow were hidden and cared for by their followers.

Many religious Jews held the view that their sufferings were

preliminary to the coming of the Messiah. There were many

instances of heroism by ultra-Orthodox Jews in the face of the

death. Hillel *Zeitlin, the famous religious writer, arrived

at the "Umschlagplatz" (assembly point) during the 1942

deportation, proudly dressed in his religious garb. Janusz

*Korczak, the director of the Jewish orphanage, continued to

give hope and courage to his wards until he boarded the death

train together with the children.

FORMATION OF RESISTANCE.

[Racist Zionists - pogrom of 1940 - underground resistance

work - ghetto newspapers]

The main form of resistance in the ghetto revolved around the

underground political life which existed throughout the German

occupation. The most active were the [[racist]] Zionist groups

- *Po'alei Zion,*Ha-Shomer ha-Za'ir (Ẓa'ir), *Deror, *Betar,

*Gordonia, as well as the [[Socialist party]] Bund and the

Communist-inspired Spartakus organization.

As early as Passover 1940 the Germans, with the cooperation of

Polish hooligans, provoked a pogrom in the Jewish district.

Underground Jewish groups organized effective self-defense.

After the ghetto was established, underground activity

increased, as the purely Jewish environment offered better

security against denunciations and infiltration of German

police agents into the ranks of the underground. The political

underground movements in the ghetto engaged in such activities

as disseminating information, collecting documents on German

crimes [[and of the collaborators]], sabotaging German

factories, and preparing for armed resistance.

A series of illegal periodicals appeared in Hebrew, Yiddish,

and Polish. Among the best known were the following

Hebrew publications: Deror,

circulated by the *He-Halutz (He-Ḥalutz) organization, El Al, Itton ha-Tenu'ah, and Neged ha-Zerem by Ha-Shomer

ha-Za'ir (Ẓa'ir); Magen

David by Betar; Sheviv

by the General [[racist]] Zionists;

Yiddish publications: Bafrayung

[[Liberation]] by He-Halutz (He-Ḥalutẓ); Morgenfray and Biuletin by the Bund;

and Polish publications: Awangarda

[[Avangarde]] by Po'alei Zion; Jutrznia and Plomienie by Ha-Shomer ha-Za'ir (Ẓa'ir).

[Jewish underground fighting

organizations]

The first Jewish military underground organization, Swit, was

formed in December 1939 by Jewish veterans of the Polish army.

Most of its members were Revisionists. The organization was

headed by David Apelbaum and Henry Lipszyc, aided by a Polish

major, Henryk Iwanski.

Early in 1942 a second underground fighting organization

emerged, created by four [[racist]] Zionist groups: Po'alei

Zion, Ha-Shomer ha-Za'ir (Ẓa'ir), Zionist Socialists, and

Deror, as well as the Communist organization. It soon became

known as the anti-Fascist bloc. Its leaders were Szachna

Sagan, Aron Lewartowski, Josef Kaplan, and Josef Sak. Four

commanders were appointed: Mordecai *Anielewicz, Pinkus

Kartin, Mordecai Tenenbaum, and Abram Fiszelson.

The Bund did not join the bloc but created its own fighting

organization "Samo obrona" (self-defense) under the command of

Abraham Blum. None of the three military organizations of the

ghetto succeeded in acquiring arms prior to July 22, 1942,

when mass deportations to *Treblinka death camp were initiated

by the Nazis [[and their collaborators]].

FIRST MASS DEPORTATIONS.

[Deportation wave of 1942 from the Warsaw ghetto]

The deportations were preceded by a series of terrorizing

"actions", when scores of people were dragged out of their

homes and murdered in the streets. Just one day before the

mass deportations to Treblinka began (July 21, 1942), 60

hostages were taken to the Pawiak Prison. Three days later,

the president of the Judenrat, Adam Czerniakow, committed

suicide following a demand by the Nazis that he cooperate with

them in the deportations. His successor, Maksymilian (Marek)

Lichtenbaum, also an engineer, obeyed the Nazi orders. The

number of deportees averaged 5,000-7,000 daily, sometimes

reaching 13,000. Some of the victims, resigned to their fate

as a result of starvation, reported voluntarily to the (col.

349)

"Umschlagplatz" [[assembly point]], lured

by the sight of food which the Germans offered to

the volunteers, and by the promise that their

transfer to "the East" meant they would be able to

live and work in freedom.

In the beginning, the Germans exempted from

deportation employees of the ghetto factories,

members of the Judenrat and Jewish police, and

hospital personnel, as well as their families.

Thousands of Jews made feverish attempts to obtain

such employment certificates. In the course of time

even these "safe" categories were subject to

deportation.

The number of victims, including those murdered in

the ghetto and those deported to Treblinka, totaled

approximately 300,000 out of the 370,000 inhabitants

in the ghetto prior to July 1942. This major Aktion lasted from

July 22 until Sept. 13, 1942 [[52 days]]. Following the

deportations, the ghetto area was drastically constricted so

that some factories and several blocks of buildings were left

outside the new walls and cordoned off with barbed wire to

prevent anyone finding shelter there. The Germans also fixed

the number of inhabitants allowed to remain in the ghetto at a

maximum of 35,000 persons.

ACTIVE RESISTANCE. [Fighting

organizations - ZOB - armed resistance since 1942 with arms,

manufacturing, and bunkers]

The leaders of the underground movements appraised the new

situation. At their first meeting, they decided to create the

Jewish Fighting Organization (Zydowska (Żydowska) Organizacja

Bojowa - ZOB), and take active steps to oppose further

deportation. A few members of the underground managed to

escape from Treblinka, and brought to the ghetto information

about the real fate that awaited the deportees, namely

physical annihilation. Because of the blockade it was not even

possible to pass this information on to the non-Jewish

population.

Some 30,000-35,000 Jews, most of them factory workers and

their families, legally remained in the ghetto and were

employed within or outside the ghetto. In addition, there were

between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews living on in the ghetto

"illegally". By the end of 1942 there was an influx of several

thousand Jews from the labor camps which had been closed. At

this time some Jews hiding on the "Aryan" side were seized and

returned to the ghetto.

In this period intensive preparations were made for armed

resistance. The Bund also joined the ZOB, while the

Revisionists continued to adhere to their separate

organization, Swit.

Appeals were made to several Polish underground organizations

for the acquisition of weapons. An emissary of the ZOB, Arie

(Jurek) Wilner, succeeded in persuading the commanders of one

of the Polish underground armies (Armia Krajowa) of the

necessity of supplying weapons to the ghetto underground and,

after long negotiations, about 100 firearms and some hand

grenades were sent into the ghetto.

Another small quantity of arms was supplied by the Communist

"People's Guard". The Revisionists also obtained several loads

of arms from two Polish underground organizations led by Major

H. Iwanski and Captain Szemley (Cesary) Ketling. Several

secret workshops were established in the ghetto to manufacture

homemade hand grenades and bombs, and some additional arms

were bought on the black market.

At the same time, a network of bunkers and subterranean

communication channels was constructed to enable combat

against the superior German forces and to protect the

non-fighting population.

[Deportation wave of January

1943 from the Warsaw ghetto - resistance and 4 days street

fight - stopped deportations - about 1,000 Jews murdered in

the ghetto]

The second wave of deportations began on Jan. 18, 1943, when

the Nazis broke into the ghetto, surrounded many buildings,

and deported the inhabitants to Treblinka. They liquidated the

hospital, shot the patients, and deported the personnel. Many

factory workers who had been employed outside the ghetto were

included among the deportees. The underground organizations,

insufficiently equipped and ill-prepared, nevertheless offered

armed resistance, which (col. 350)

turned into four days of street fighting. This was the first

case of street fighting in occupied Poland. The Germans [[and

their collaborators]] fearing the impact of this outburst on

other parts of Poland, stopped the deportations, and attempted

to carry out their aim by "peaceful" means, namely by

voluntary registration for the alleged labor camps. The

underground, in turn, conducted an intensive information

campaign about the real intentions of the Nazis [[and their

collaborators]]. As a result the second wave of deportations

was suspended after four days, during which the Germans [[and

their collaborators]] managed to send only 6,000 persons to

Treblinka. About 1,000 others were murdered in the ghetto

itself.

THE GHETTO UPRISING. [Street

fights - houses burning down April-May 1943]

After this Aktion,

daily life in the ghetto was paralyzed. Walking in the street

was punishable by death. Only groups of workers marching under

armed guard were to be seen. Social institutions ceased to

function and the Judenrat, most of whose members were killed

in the January Aktion,

were reduced to a small office. The underground organizations,

however, were preparing for armed resistance in case a further

attempt would be made by the Germans [[and their

collaborators]] to liquidate the ghetto. Mordecai Anielewicz

now headed the ZOB. The members of his command were: Yizhak

(Yiẓḥak) (Antek) *Cukierman, Hersz Berlinski, Marek Edelman,

Zivia (Ẓivia) Lubetkin, and Michal Rojzenfeld.

The entire force was divided into 22 fighting units, each unit

affiliated with one of the political groups. Israel Kanal was

commander of the units operating in the central area of the

ghetto; and Eleazar Geller and Marek Edelman commanded the

factory units. The ZOB underground headquarters were at 18

Mila Street. The Revisionist commanders were Leon Rodal, Pawel

Frenkiel, and Samuel Luft.

On April 19, 1943, a German force, equipped with tanks and

artillery, under the command of Col. Sammern-Frankennegg,

penetrated into the ghetto in order to resume the

deportations. The Nazis met with stiff resistance from the

Jewish fighters. Despite overwhelmingly superior forces, the

Germans were repulsed from the ghetto, after suffering heavy

losses. Sammern-Frankennegg was relieved of his command, and

Gen. Juergen *Stroop, appointed in his stead, immediately

resumed the attack. Street fighting lasted for several days,

but when the Germans [[and their collaborators]] failed in

open street combat, they changed their tactics. Carefully

avoiding any further street clashes, the Germans [[and their

collaborators]] began (col. 351)

systematically burning down the houses. The inhabitants died

in the flames, while those hiding in the canals and bunkers

were killed by gas and hand grenades. Despite these

conditions, the Jewish fighting groups continued to attack

German soldiers until May 8, 1943, when the ZOB headquarters

fell to the Germans. Over a hundred fighters including

Anielewicz, died in this battle. Several units continued to

fight even after the fall of the ZOB and Revisionist

headquarters. Armed resistance lasted until June 1943. With

the help of the Polish "People's Guard" some 50 ghetto

fighters escaped from the ghetto and continued to fight the

Germans in the nearby forests as a partisan unit named in

memory of Anielewicz.

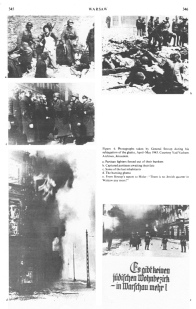

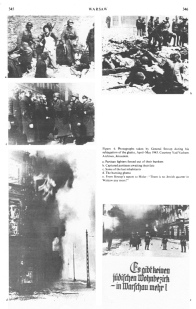

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 345. The

burning ghetto, April-May 1943 Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 345. The

burning ghetto, April-May 1943

|

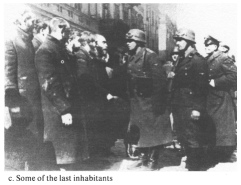

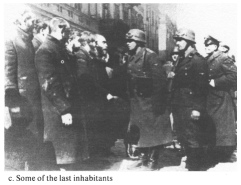

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 345. Some of

the last inhabitants confronted with the Nazi

army.

|

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw,

vol. 16, col. 345. Jewish partisan fighters

forced out of their bunkers. [[See the laughing

German soldiers, but 2 years afterwards they had

nothing to laugh any more...]] Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol.

16, col. 345. Jewish partisan fighters forced

out of their bunkers. [[See the laughing German

soldiers, but 2 years afterwards they had

nothing to laugh any more...]]](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Warschau-d/EncJud_Warsaw-band16-kolonne345-jued-partisanen-aus-bunkern-45pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 345. Jewish

partisan fighters forced out of their bunkers.

[[See the laughing German soldiers, but 2 years

afterwards they had nothing to laugh any more...]]

|

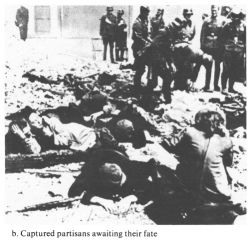

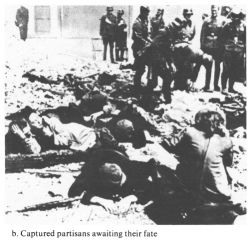

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 346. Captured

partisans awaiting their fate. Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 346. Captured

partisans awaiting their fate.

|

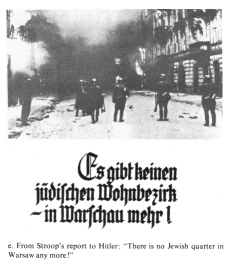

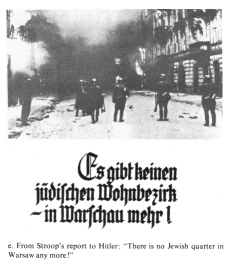

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 346. From

Stroops's report [[with a photo of the burning

Warsaw ghetto]] to Hitler: There is no Jewish

quarter in Warsaw any more!" (Es gibt keinen

jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr!)

Photographs taken by General Stroop during his

subjugation of the ghetto, April-May 1943. Courtesy

Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

|

[Moral effect of Warsaw

ghetto uprising - sporadic resistance from the ruins until

August 1943]

The Warsaw ghetto uprising had an enormous moral effect upon

Jews and non-Jews throughout the world, especially since it

was prepared and carried out under conditions which

practically excluded a

priori any attempt at armed resistance. Despite the

vastly unequal forces, the uprising continued for a long time

and constituted the largest battle in occupied Europe before

April 1943 (excepting in Yugoslavia).

This battle also had its impact upon the Polish population,

resulting in the intensification of resistance by the Poles as

well as by Jews throughout the country. On May 16, 1943,

Stroop reported to his superiors on the complete liquidation

of the Warsaw ghetto. As a token of his victory he blew up the

Great Synagogue on Tlomacka Street. According to his report,

the Germans [[with their collaborators]] in the course of one

month's fighting had killed or deported over 56,000 Jews. The

Germans themselves officially suffered 16 dead and 85 wounded

between April 29 and May 15, but it is conjectured that the

German casualties were in fact much higher. In the course of

the following months, the Germans penetrated the empty ghetto

and hunted down the remnants hiding in the ruins, often using

fire to overcome sporadic resistance, which continued until

August 1943.

[[In the following month in September 1943 Rome was falling]].

The Warsaw ghetto uprising became an event of world history

when details of what happened became known after the war.

Among the writers who depicted life in the ghetto and the

underground fighters were Yizhak (Yiẓḥak) Katznelson, John

Hersey, and Leon *Uris.

[Jews in Warsaw 1943-1944 on

the "Aryan" side]

After the liquidation of the ghetto, the surviving members of

the ghetto leadership continued underground (col. 352)

work on the "Aryan" side of Warsaw. The underground's main

activity was to assist Jews living on the "Aryan" side, either

in hiding or by means of forged documents. According to their

figures, the number of Jews on the "Aryan" side reached 15,000

(May 1944). They also established contact with Jewish

organizations abroad and received financial assistance. Among

their leaders were Adolf *Berman of Po'alei Zion and Leon

Fajner of the Bund. Emmanuel *Ringelblum continued his

scientific work of collecting evidence on Nazi crimes until

May 1944, when he was seized and executed.

[[There must have been a declaration of the Nazi occupation

forces that Warsaw was "judenrein" ("free of Jews"), but it's

not mentioned in the article]].

[Warsaw uprising in August

1944]

Hundreds of Jews were active in the Polish underground of

Greater Warsaw, particularly Hanna Szapiro-Sawicka, Niuta

Tajtelbaum, Ignacy Robb-Narbutt, Menasze Matywiecki, and

Ludwik Landau. When the Polish uprising in Warsaw broke out on

Aug. 1, 1944, over 1,000 Jews in hiding immediately

volunteered to fight the Germans [[and their collaborators]].

Hundreds of them fell in the battle, among them a member of

the high commando of the People's Army, Matywiecki, and Pola

Elster, a member of the Polish National Council. In addition,

the remnants of the ZOB, under the commando of Cukierman, and

a group of liberated prisoners from the city concentration

camp, participated in the uprising.

[DE.D.]

[[...]] About 6,000 Jewish soldiers participated in the battle

for the liberation of Warsaw. Warsaw's eastern suburb, Praga,

was liberated [[occupied by Communist terror]] in September

1944,and the main part of the city on the left bank of the

Vistula [[Germ.: Weichsel]] on Jan. 17, 1945. On that day only

200 Jewish survivors were found in underground hideouts in the

ruins of destroyed Warsaw. [[...]]

Post-War Developments.

[Returned Jews from central

Russia - Jewish institutions since 1945 in Warsaw]

[[...]] By the end of 1945 about 5,000 Jews had settled in

Warsaw. That number was more than doubled [[to over 10,000

Jews]], when Polish Jews, who had survived the war in the

Soviet Union, returned. Warsaw became the seat of the Central

Committee of Polish Jews. On April 19, 1948 (the fifth

anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising) a monument executed

by N. Rapaport in memory of the ghetto fighters was unveiled

in the square called "The Ghetto Heroes' Square". In 1949 a

number of Jewish cultural institutions (The Jewish Historical

Institute, the Jewish Theater, editorial staffs of the Yiddish

papers Folksshtime

[[People's Voice]] and Yidishe

Shriften [[Yiddish Papers]]) were transferred from

Lodz to Warsaw. A club for Jewish youth, "Babel", was opened

there and one synagogue was rebuilt.

[Emigrations waves from

Warsaw 1945-1970]

After the war Warsaw Jews left Poland in three main waves: in

1946-47 after the great pogrom in *Kielce; in 1957-58; in

1967-68 when the Polish government launched its official

anti-Semitic campaign. After 1968 Jewish institutions,

although officially not closed, had actually ceased to

function. The number of remaining Jews, mostly aged people,

was estimated at 5,000 in 1969. For further details see

*Poland.

[DE.D./S.KR.]

[[Precise numbers how many Jews were emigrating are missing in

this article]].

| Memorial |

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Memorial

of the Warsaw ghetto uprising with group of persons

and candle stand (menorah), from Nathan Rapaport,

1948. Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Memorial

of the Warsaw ghetto uprising with group of persons

and candle stand (menorah), from Nathan Rapaport,

1948. |

x

|

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Relief of

the memorial of the Warsaw ghetto uprising from

Nathan Rapaport, 1948. Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Relief of

the memorial of the Warsaw ghetto uprising from

Nathan Rapaport, 1948. |

Bibliography

-- S. Dubnow: History of the Jews in Russia and Poland, 3

vols. (1916-20), index

-- R. Mahler: Divrei Yemei Yisrael, Dorot Aharonim, 1, pt. 3

(1955); pt. 4 (1956), 2, pt. 1 (1970), indexes

-- idem: Toledot ha-Yehudim be-Polin (1946), index

-- A. Levison: Toledot Yehudei Varshah (1953)

-- EG (1953, 1959)

-- Pinkas Varshe (Yid., 1955)

-- E. Ringelblum, in: Historishe Shriftn, 2 (1937), 248-68

-- idem, in: Zion, 3 (1938), 246-66, 337-55

-- idem, in: YIVO Bleter [[YIVO Papers]], 13 (1938), 124-32

-- idem: Kapitlen Geshikhte ... (1953)

-- idem: Geshikhte fun Yidn in Varshe [[History of the Yiddish

People in Warsaw]], 1-3 (1947-53)

-- A. Kraushar: Kupiectwo warszawskie (1929)

-- H.D. Friedberg: Toledot ha-Defus ha-Ivri be-Polanyah

(1950), 109-15

-- B. Weinryb, in: MGWJ, 77 (1933), 273 ff.

-- H. Lieberman, in: Sefer ha-Yovel ... A. Marx (1943), 20-21.

See also bibl. Poland.

HOLOCAUST

For a full bibliography see Holocaust, General Survey -

Sources and Literature, Sections 3, 4

-- G. Reitlinger: Final Solution (1968), 260-326, and passim,

incl. bibl.

-- r. Hilberg: Destruction of European Jews (1961), index

-- Central Commission for War Crimes: German Crimes in Poland

[[the collaborators are not mentioned]], 2 vols. (1946-47)

(col. 353)

-- American Federation for Polish Jews: Black Book of Polish

Jewry (1943) (col. 353-354)

-- American Jewish Black Book Committee: Black Book (1945)

-- A. Czerniakow: Yoman Geto Varshah (1968)

-- C.A. Kaplan: Scroll of Agony: Warsaw Ghetto Diary (1965)

-- J. Tenenbaum: In Search of a Lost People (1949)

-- idem: Underground, the Story of a People (1952)

-- B. Mark: Der Aufstand im Warschauer Ghetto [[Warsaw Ghetto

Uprising]] (1959)

-- idem. (ed.): The Report of Juergen Stroop (1958), includes

introduction and notes

-- J. Kermish (ed.): Mered Getto Varshah be-Einei ha-Oyev

(1966), Eng. introd. and notes

-- P. Friedman: Martyrs and Fighters (1954)

-- Y. Gruenbaum (ed.): Varshah (1953), 601-815

-- J. Sloan (ed.): Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto. The Journal

of Emmanuel Ringelblum (1958)

-- B. Goldstein: Five Years in the Warsaw Ghetto (1961)

-- idem: The Stars Bear Witness (1950)

-- D. Wdowinsky: And We Are Not Saved (1963)

-- A. Donat: The Holocaust Kingdom (1965)

-- N. Blumental and J. Kermish (eds.): Ha-Meri ve-ha-Mered

be-Getto Varshah (1965), Eng. introd.

-- M. Berland: 300 Sha'ot ba-Getto ha-Do'ekh (1959)> (col.

354)

| Sources |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

341-342

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

343-344

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

345-346

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

347-348

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

349-350

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

351-352

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

353-354

|

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Youngsters in the streets of Warsaw ghetto.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Jewish police force. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Market place of Warsaw ghetto. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Standing in line for potatoes in the Warsaw ghetto.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 344. Old man. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Memorial of the Warsaw ghetto uprising with group of persons and candle stand (menorah), from Nathan Rapaport, 1948.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col. 351. Relief of the memorial of the Warsaw ghetto uprising from Nathan Rapaport, 1948.

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16,

col. 344. Standing in line for potatoes in the Warsaw

ghetto. [[In the background can be seen a poster for a

ballet performance]]. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto

by a German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1,

1941. Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol. 16, col.

344. Standing in line for potatoes in the Warsaw ghetto.

[[In the background can be seen a poster for a ballet

performance]]. Photo taken in the Warsaw ghetto by a

German war correspondent. Oct. 1, 1940-June 1, 1941.

Courtesy Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Warschau-d/EncJud_Warsaw-band16-kolonne343-schlangestehen-f-kartoffeln-45pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw,

vol. 16, col. 345. Jewish partisan fighters

forced out of their bunkers. [[See the laughing

German soldiers, but 2 years afterwards they had

nothing to laugh any more...]] Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Warsaw, vol.

16, col. 345. Jewish partisan fighters forced

out of their bunkers. [[See the laughing German

soldiers, but 2 years afterwards they had

nothing to laugh any more...]]](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Warschau-d/EncJud_Warsaw-band16-kolonne345-jued-partisanen-aus-bunkern-45pr.jpg)