|

|

|

<< >>

Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Yugoslavia 01: the Balkan states before 1918

Back and forth with Jewish rights - emancipation in the 19th century - Jews in commerce and parliaments

Jewish cemetery near Sarajevo, dating to the 17th century. Courtesy Federation of Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia, Belgrade

from: Yugoslavia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 16

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2020)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

<YUGOSLAVIA ("Land of the Southern Slavs"), a Socialist Federated Republic in S.E. Europe, in the Balkan Peninsula. The various elements of which Yugoslav Jewry was composed after 1918 (i.e. those of Serbia and the Austro-Hungarian countries) were distinct from one another in their language, culture, social structure, and character according to the six separate historical, political, and cultural regions of their origin. These regions were: Serbia; Slovenia; Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia; Bosnia-Herzegovina; Macedonia; and Vojvodina.

Until 1918.

SERBIA. [Back and forth with the conditions for the Jews in Serbia before 1918]

There were some Jews in Pannonia in Roman times. Jews seem to have reached *Belgrade and there were also traces of a Jewish population along the banks of the Danube during the tenth century. Some Jews penetrated into Serbia from Macedonia. During the ninth and tenth centuries many of the Serbians converted to Christianity. The faith of the new Christians at that time was an amalgamation of Christianity, Judaism, and paganism. Benjamin of Tudela, the 12th-century traveler, also mentions the influence of the Jews on the inhabitants of the Balkans.

At the time of the conquest of Serbia by Sultan Murad in 1389, the Jews engaged in the sale of salt. Under Turkish rule the Jews of Belgrade played an important part in the trade between northern and southern Turkish provinces which passed through Belgrade.

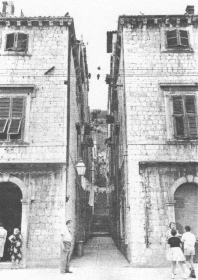

The narrow alleyway in Dubrovnik still named Jews' Street. It contains a synagogue,

one of the oldest in Europe, established in 1352. Courtesy Z. Efron, En-Harod.

During the period of the Austrian rule over northern Serbia from 1718 to 1739, the government's attitude toward the Jews was generally good.

During the Serbian wars of independence (1804-30), some of the Jews fled from Belgrade and in 1807 founded a community, which numbered 280 persons in *Zemun. The Jews supplied arms to the revolutionary army.

However, the independence movement, which fomented (col. 868)

rebellions against the Turks from time to time, frequently attacked the Jews. In 1831 the Serbian government decreed certain limitations on the crafts in which the Jews were engaged.

In 1845 they were excluded from tailoring and shoemaking. During the reign of Milosh Obrenovich, the prince of Serbia, there was a favorable change in the condition of the Jews. However, with the ascent of the Karageorgevich dynasty in 1842, which supported the interests of the Serbian merchants who envied their Jewish rivals, the condition of the Jews took a turn for the worse. A decree of 1856 forbade the Jews to reside in the provincial towns. There were then 2,000 Jews in Serbia. About 1,000 of them settled in Belgrade, while the rest were dispersed in other towns.

When Prince Milosh returned to power in 1858, the condition of the Jews temporarily improved. However,during the reign of his son, Prince Michael (1860-1868), who was also influenced by the Serbian merchants, the persecutions were renewed. An expulsion decree of 1861 against 60 Jewish families of Sabac (¦abac) was changed during the same year into another decree which authorized the Jews - and this only in their places of residence - to practice the same professions as they had engaged in before February 28, 1861. The Jewish merchants, also in their places of residence, were authorized to trade in raw materials and foodstuffs. These rights, however, could not be transferred to their successors. Concerning real estate, the new decree confirmed a former one which prohibited the purchase of property in the provincial towns.

[Emancipation without emancipation - expulsions in 1873 - equality only since 1889]

After the assassination of Michael and the enthronement of Milan Obrenovich, the Serbian parliament voted the emancipation of all citizens, but at the same time confirmed the restrictive decrees of 1856 and 1861. In 1873 the Jews were expelled from the towns of Sabac (¦abac), Smederevo, and Pozarevac (Po¸arevac). The treaty of Berlin of 1878 accorded civil and political equality to the Jews of Serbia, but it was only in 1889 that the Serbian parliament proclaimed the complete equality of all Serbians without distinction of origin and religion and abolished the restrictive decrees of the previous years.

In 1895 there were 5,102 Jews in Serbia, 5,729 in (col. 869)

1900, and 5,000 in 1912. The number of Jews who participated in the Balkan Wars (1912-13) was 500. During the Serbian-Bulgarian war of 1913 and World War I many Jews were decorated [[and it can be assumed that many more also lost their lives]].

SLOVENIA. [Nothing special about Jews in Slovenia]

Jews lived in Slovenia from the 13th century until they were expelled in 1426 by Emperor Maximilian I of Austria. The biggest rabbinical center was at Maribor (Marburg) in the Styria district. Maribor had a "Jewish Street" as early as 1277 near the river Drava (Drau) and a synagogue inside the walled city. Rabbi Israel *Isserlein taught there. His official title was "Landesrabbiner fuer Steiermark, Krain, und Korushka" [["Rabbi in the countryside in Steiermark, Krain and Korushka]]. He was succeeded by his pupil R. Joseph B. Moses. Other Jewish communities existed at Ptuj (Poetovia), Celje, Radgona, and Ljubljana. Jews were engaged in viticulture trade in horses and cattle.

[[It seems this article is not complete at all and all precise data between 1300 and 1918 are missing]].

CROATIA, SLAVONIA, AND DALMATIA. [Back and forth with Jewish rights]

The Croats, who penetrated into the N.W. Balkans in the seventh century and established a kingdom in the tenth, found there several Jewish communities. In the letter of Hisdai ibn Shaprut (5:10) to Joseph the king of the Khazars, there is a mention of the "king of the Gebalim" who sent a deputation, which included Mar Saul and Mar Joseph, to Caliph Abdurrahman [[Abdurraḥman]] III of Cordoba. The "king of the Gebalim, the Slavs", whose country bordered that of the Hungarians, was Kresimir (Kre¨imir), king of Croatia. The messengers informed Hisdai (Ḥisdai) that Mar Amram of the court of Khazar king had come to the land of the "Gebalim".

There is little information on the Jews of Croatia from the 10th to 15th centuries. Some Jews lived in the Croatian capital *Zagreb in the 13th and 14th centuries, when they had a chief entitled "magistratus Judaeorum", and a synagogue. Others settled between the Sava and Drava (Drau) and Danube rivers during the 15th century. As long as the economy of the country required the presence of the Jews, they lived there without hindrance. As soon as they were superfluous, they were persecuted and driven out. The Jews were expelled from Croatia and Slavonia in 1456. Croatia together with Hungary passed to the Hapsburgs in 1526, and no Jews lived there for the next 200 years.

Toward the end of the 18th century, Jews from Hungary, Bohemia, Moravia, and especially Burgenland (east Austria) resettled there. In 1776 Jews came to *Osijek and in 1777 to Varazdin (Vara¸din) and a limited number to Zagreb. At that time there was also a Jewish community in Zemun. R. Judah b. Solomon Hai *Alkalai (1798-1878), who lived there from 1826 to 1843, also propagated the ideals of the movement for the settlement of Erez Israel (Ereẓ Israel) in Sabac (¦abac) and Belgrade. A census of the Jews in 1773, during the reign of Maria Theresa, revealed only 25 families.

[Toleranzpatent in 1782 and further Jewish rights - full emancipation in Croatia and Dalmatia in 1873]

It was only after the publication of the *Toleranzpatent in 1782 by Emperor Joseph II that the situation improved and more Jews arrived from the north and the south. The right of residence was granted in 1791. Further rights were granted in 1840, but the "tolerance tax" remained in force. The Jews of Croatia and Dalmatia only received their full emancipation in 1873. Until 1890 the community of Osijek was the most prominent, but from that year the community of Zagreb, founded in 1806, became the leading one. In 1841 an Orthodox congregation was founded in Zagreb. The Jews of Croatia were mostly merchants and some were artisans.

[Dalmatia: commerce - blood libels - refugees from Spain and Portugal, and from Ancona - ghetto in Split 1738-1806 - French rule - Austro-Hungarian law]

Jews arrived in Dalmatia with the Roman armies. In Solin (Salona), in the vicinity of *Split (Spalato), there are remains of a Jewish cemetery of the third century. There was a Jewish community in Solin until 641, when Solin was destroyed by the Avars. During the Middle Ages, the Jews of Split and Ragusa (*Dubrovnik) engaged in commerce and especially in the brokerage of the trade between Dalmatia and Italy and the Danubian countries.

Under the (col. 870)

autonomous republic which was established in Dubrovnik during the 15th century, the Jews lived in relative tranquility. The Christian clergy, however, attempted to oppress them and succeeded in spreading *blood libels in Dubrovnik in 1502, 1622, and 1662.

During the 16th century, refugees from Spain and Portugal settled in Dalmatia. When Pope Paul IV expelled the Jews from Ancona in 1556, a considerable number of them requested asylum in Dubrovnik. These included the physician *Amatus Lusitanus and his friend the poet *Pyrrhus Didacus, both Marranos.

In 1738 the condition of the Jews in Dalmatia deteriorated. The Jews of Split lived in a ghetto until the arrival of the French in 1806. In 1906 the Austro-Hungarian government passed a law which defined the status of the Jewish communities of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia.

[Figures]

In 1870 there were already 10,000 Jews in Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia; 13,488 in 1880; and 17,261 in 1890. After World War I there were 20,000 Jews in Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia.

The Great Synagogue of Zagreb, Yugoslavia, built 1867 destroyed by the Nazis in 1941.

Courtesy Jacob Altaras, Giessen, Germany

BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA. [Jewish refugees since 1492 from Spain and Portugal - Jewish refugees from Ofen in 1686 - Jews in the Ottoman parliament in 19th century]

One of the republics in central Yugoslavia with the largest Muslim population (750,000). There is no evidence of the existence of a Jewish community in Bosnia before the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Tombstone inscriptions prove the existence of Jews in *Sarajevo in 1551. A special quarter was allocated to them later in the 16th century and they lived there until the conquest of the town by the Austrians in 1878.

During the rule of Daudji Pasha, who was appointed in 1635, the relations between Turkey and Venice became strained. This had an adverse effect on the commerce of the local Jews. During the siege of Ofen in 1686 many Jews fled to Sarajevo, including Zevi (Ẓevi) Hirsch *Ashkenazi (Hakham Zevi (Ḥakham Ẓevi), who was appointed hakham (ḥakham) [[spiritual leader]] there.

A change for the worse in the situation of the Jews of Sarajevo occurred in 1833. In was only after payment of a heavy (col. 871)

ransom that the Jews were saved from the danger of riots and blood libel. The laws of 1839, 1856, and 1876, which granted the Jews of Turkey equality of rights with the other citizens, also applied to the Jews of Bosnia. From then onward, some Jews were elected to the Ottoman parliament in Constantinople and the municipal councils.

In 1876 Xaver Effendi Barukh was sent to the parliament as the representative of Bosnia. Isaac Effendi Shalom was a member of the Majlis Idarch ("Advisory Council to the Vali"). Upon his death, his place was filled by his son Solomon Effendi Shalom, who was also a representative in the parliament. Two Jewish delegates were sent to the Landstag [[local district parliament]] which was opened in 1910.Besides Sarajevo, there was also Jewish communities in the towns of *Travnik, *Banja Luka, Bijeljina, and others.

The following data are available on the number of Jews in Bosnia from the end of the 18th century. There were 1,500 Jews in 1780; 8,213 in 1895; 10,000 (Sephardim) in 1923; 13,701 in 1926; 14,000 in 1941 (together with Herzegovina); and 1,298 in 1958. In addition to the Nazis and the Ustase (Usta¨e) who were active in Bosnia in World War II, the former mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-*Husseini (Hājj Amīn al-*Husseini), succeeded in enlisting the support of local authorities in the expulsion of the Jews from the province and their extermination.

MACEDONIA. [Back and forth with the rights for Jews in Macedonia]

The earliest Jewish presence was really in Macedonia and Dalmatia. Philo mentions the Jews of Macedonia in Embassy to Gaius (Legatio ad Gaium), translated into English by F.H. Colson (1962), par. 281, while the apostle Paul delivered sermons in its communities (Acts 20; 1-2).

A Greek inscription on a pillar of the church - a former synagogue - in Stobi (in the vicinity of the town of Bitolj (*Monastir)) and now preserved in the Jewish museum of Belgrade, serves as evidence of the Jewish settlement during the second and third centuries. In it, Claudius Tiberius Polycharmos relates his Jewish way of life.

During the Middle Ages, Jews lived in Bitolj (Monastir), Skoplje, *Ochrida, and Struga. During the reign of the Serbian emperor Stefen Dushan there is a mention of Jewish farmers in Macedonia (conquered by Dushan in 1353). During the 14th century, the renowned grammarian Judah (Leon) Moskoni, whose version of Josephus was published in Constantinople in 1510, lived in Ochrida. During the 16th century there were Jewish communities in *Skoplje, Bitolj, *Nis (Ni¨), Smederovo, and Pozarevac (Po¸arevac).

At the time, Skoplje was a commercial center. The Jews traded in wool clothes, "kachkaval" cheese, and also engaged in commerce between Salonika and Constantinople on the one hand and Western Europe on the other. In 1680 *Nathan of Gaza died in Skoplje. His admirers made an annual pilgrimage to his tomb.

When the armies of Leopold I approached Skoplje in 1689, the Jews hurriedly abandoned the city. Their synagogues were burnt down and the wall surrounding their quarter also was destroyed by the flames. The Jewish population of Stip (¦tip) was of Salonikan origin. During the 17th and 18th centuries, R. Abraham Motal ha-Paytan ("the hymnologist") and R. Reuben b. Abraham, who wrote the work Derekh Yesharah (Leghorn [[Livorno]], 1788) and in Ladino Tikkunei ha-Nefesh Salonika, 1765-75), lived in this town. At the time of the upheavals in Turkey which preceded the Balkan Wars, more Jews settled in Macedonia.

VOJVODINA. [Frontier region without Jews until the 1840s - commerce]

This was an Austrian frontier region and the residence of Jews was prohibited there. Jews first settled in Vojvodina during the 18th century, but they were exceptions. Most Jewish communities were founded in the 1840s. The Jews of Vojvodina engaged in commerce and in import-export trade. Before World War II there were 19,200 Jews in Vojvodina (Backa (Bačka), 14,800; Banat, 4,400).

In 1952 there were Jewish communities: in *Novi Sad - 275; (col. 872)

*Subotica, 403; *Sombor, 46; Senta, 28; and Pancevo (Pančevo), 34 following immigration to [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel by most of the survivors of the Holocaust.> (col. 873)

| Teilen

/ share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter |

|

|

|