Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Lisbon

Rich cultural

contribution since Afonso I - Anti Jewish laws since

Ferdinand I - pogroms and popular anti-Judaism - Spanish

Jews coming in 1492 - expulsion from Portugal in 1496 -

persecution of Conversos - emancipation of New

Christians in 1773 - emancipation of Jews in 1910 -

Jewish influx from Eastern Europe and from NS

territories for emigration overseas - numbers 1945-1970

- scholars and printing

from: Lisbon; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 11

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

<LISBON, capital of

*Portugal.

[[Jews since kingdom of

Portugal under Affonso I - rich cultural contribution]]

The Middle Ages.

Jews were apparently settled in Lisbon in the 12th century, at

the time of the conquest of the territory from the Moors and

the establishment of the kingdom of Portugal by Affonso I

(1139-85). For a period of two centuries they appear to have

lived in tranquility, sharing the lot of their coreligionists

in the rest of the country. Many Jews were prominent in court

circles as tax farmers, physicians, or astronomers; the

almoxarife Dom Joseph ibn

Yaḥya, descendant of a family founded by a Jew who accompanied

the first king on his conquest of the country, constructed a

magnificent synagogue at his own expense in 1260.

When the religious and political organization of the

communities of Portugal was revised by Affonso III (1248-79),

Lisbon became the official seat of the *

arraby mór, or chief

rabbi. the most important incumbent of this office was Dom

Moses Navarro, physician to Pedro I (1357-67), who, with his

wife, acquired a large landed property near Lisbon.

Encyclopaedia judaica: Jews in Lisbon, vol. 11, col. 301,

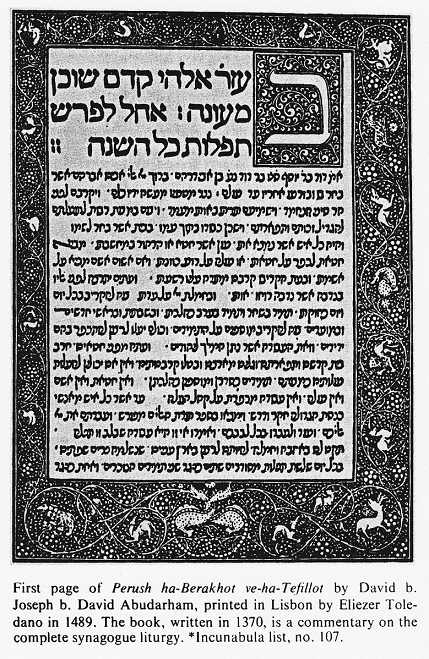

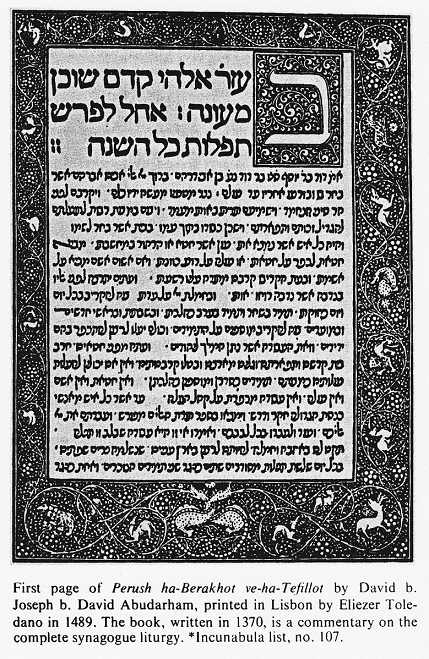

Perush of 1370: First page of

Perush ha-Berakhot ve-ha-Tefillot

by David b. Joseph b. David Abudarham, printed in Lisbon by

Eliezer Toledano in 1489. The book, written in 1370,

is a commentary on the complete synagogue liturgy.

*Incunabula list, no. 107.

This initial period of prosperity came to an end in the reign

of Ferdinand I (1367-83). When Lisbon was captured by 1373,

the Jewish quarter was sacked and many Jews killed. After the

king's death, the Jews were considered by the populace to be

at the root of the rapacious policies of the queen dowager

Leonora - notwithstanding the fact that she had deposed the

Jewish collector of taxes at Lisbon, as well as Dom Judah, the

former royal treasurer.

[Government under Aviz

dynasty - popular anti-Judaism - protection of the Jews

under John I]

A popular (col. 299)

revolt led to the accession to the throne of the master of

Aviz, the first of a new dynasty. The feeling in Lisbon

against the Jews became extreme, and the people wished to take

violent steps to discover the treasures left by the late

instrument of royal greed. An anti-Jewish reaction followed in

the political sphere. Nevertheless, the new king (known as

John I) did his best to protect the Jews against actual

violence, though they were henceforth excluded from the

positions of trust they had formerly occupied and were forced

to make disproportionate contributions to the gift exacted by

the city for presentation to the new king. Toward the close of

his life, the latter became a little more tolerant.

[King Duarte with separation

decree - but mitigated]

There was a reaction, however, under his son, Duarte

(1433-38), who attempted to enforce the complete separation of

Jews and Christians. This led to a protest by the community of

Lisbon, and as a consequence the severity of the recent decree

was mitigated (1436).

Persecution and Expulsion.

[Popular pogroms 1455-1492]

Popular feeling, nevertheless, continued antagonistic. In

1455, the Côrtes of Lisbon [[Court of Lisbon]] demanded

restrictions against the Jews. The Portuguese sovereigns had

not permitted the wave of rioting which swept through the

Iberian Peninsula in 1391 to penetrate into their dominions.

Nevertheless, as a result of some disorder in the fish market,

there was a serious anti-Jewish outbreak in Lisbon toward the

close of 1449 which led to many deaths, and another (in the

course of which Isaac *Abrabanel's library was destroyed) in

1482.

[Spanish Jews fleeing to

Portugal and to Lisbon 1492 - plague because of bad

conditions]

Owing to the tolerant if grasping policy of John II, a number

of the exiles from Spain were allowed to enter Lisbon after

the expulsion of 1492. Their crowded living conditions led to

an outbreak of plague and the city council had them driven

beyond the walls. Royal influence, however, secured the

exemption from this decree of Samuel Nayas, the procurator of

the Castilian Jews, and Samuel Judah, a prominent physician.

[Expulsion by port of Lisbon

1496/97]

When in 1496/97 the Jews were to be expelled from Portugal,

Lisbon alone was assigned to them as a port of embarkation.

Assembling there from every part of the country, they were

herded in turn into a palace known as Os Estãos [[place "where

they are"]], generally used for the reception of foreign

ambassadors; here the atrocities of forced conversion were

perpetrated. Simon Maimi, the last

arraby mór, was one of the few who was able

to hold out to the end. Thus, the community of Lisbon, with

all the others of Portugal, was driven to embrace a titular

Christianity.

[Flight to Turkey (e.g.

Smyrna) and Greece (Salonika)]

In the period immediately before and after the general

expulsion, however, some individuals managed to escape. They

probably contributed a majority of the members to the

"Portuguese" synagogues in various places in the Turkish

Empire, such as Smyrna (*Izmir), while at *Salonika and

elsewhere they established separate congregations which long

remained known by the name of "the kahal [[community board]]

of Lisbon".

[The persecution of the

converted Jews ("New Christians")]

Lisbon was the seat of the most tragic events in *Conversos

history during the course of the subsequent period. On

Whitsunday, 1503, a quarrel in the Rua Nova (the former Jewish

quarter) between some *New Christians and a riotous band of

youths led to a popular uprising, which was suppressed only

with difficulty. In 1506, on the night of April 7, a number of

New Christians were surprised celebrating the Passover

together. they were arrested, but released after only two

days' imprisonment. On April 19 trouble began again, owing to

the conduct of a Converso who scoffed at a miracle which was

reported to have taken place in the Church of Santo Domingo.

He was dragged out of the church and butchered, and a terrible

massacre began - subsequently known as

A Matança dos Christãos Novos

("The slazing of the New Christians"). The number of victims

was reckoned at between two and four thousand, one of the most

illustrious being João Rodriguez Mascarenhas, a wealthy tax

farmer and reputedly the most hated (col. 300)

man in Lisbon. Sailors from the Dutch, French, and German

ships lying in the harbor landed to assist in the bloody work.

the king, Manoel, sharply punished this outbreak, temporarily

depriving Lisbon of its erstwhile title "Noble and Always

Loyal", fining the town heavily,k and executing a number of

the ringleaders.

The Inquisition.

[The "Holy Office" in Lisbon

- "the most active in the whole country"]

The visit of David *Reuveni (c. 1525), and the open conversion

to Judaism of Diogo Pires (subsequently known as Solomon

*Molcho), created a great stir amongst the Lisbon Conversos.

They were foremost in attempting to combat the introduction of

the Inquisition into Portugal, but their efforts were in vain.

Lisbon itself became the seat of a tribunal of the Holy Office

and on Sept. 20, 1540, the initial Portuguese auto-da-fé took

place in the capital - the first of a long series which

continued over more than two centuries.

Throughout this period, the Lisbon tribunal was the most

active in the whole country. Inquisitional martyrs who

perished there included

-- Luis *Dias, "the Messiah of Setúbal" together with his

adherents, the pseudo-prophet Master Gabriel, and the mystical

poet Gonçalo Eannes bandarra, an "Old Christian" (1542 etc.);

-- Frei Diogo da Assumpão (Aug. 3, 1603);

-- António *Homem, the "

Praeceptor

Infelix" and others of his circle (May 5, 1624);

-- Manuel Fernandes *villareal, the statesman and poet (Dec.

1, 1652);

-- Isaac de *Castro Tartas, with other Conversos captured in

Brazil (Dec. 15, 1647);

-- António Cabicho, with his clerk Manoel de Sandoval

(Dec. 26, 1684);

-- Miguel (Isaac) Henriques da Fonseca, with António de Aguiar

(alias Aaron Cohen Faya), and Gaspar (Abraham) Lopez Pereira,

all of whom were mourned by Amsterdam poets and preachers as

martyrs (May 10, 1681).

[Heavy suffering by rumors -

auto-da-fés]

At times during the Inquisition period, the New Christians as

such suffered. Thus, for example, when in 1630 a theft

occurred at the Church of Santa Engrácia at (col. 301)

Lisbon, suspicion automatically fell on the New Christians. A

youth named Simão Pires Solis was cruelly put to death; the

streets of the capital were placarded with inflammatory

notices; the preachers inveighed from the pulpits against the

"Jews"; and 2,000 persons are said to have fled from Lisbon

alone. Similarly, in 1671, when a common thief stole a

consecrated pyx from the Church of Orivellas at Lisbon,

suspicion again fell on the Conversos and an edict was

actually issued banishing them from the country (but not put

into effect).

From the accession of the House of Bragança in 1640 the power

of the Portuguese Inquisition had been restrained in some

measure, and its suspension by Pope Clement X in 1674 gave the

New Christians some respite, but it proved little less

terrible than before on its resumption in 1681.

After the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession

(1701-14), there seems to have been a recrudescence of

inquisitional power, and, in the subsequent period, it became

customary to send to Lisbon for punishment all those persons

found guilty by the other tribunals of the realm. An

auto-da-fé held at Lisbon in 1705 was the occasion of the

famous and savage sermon of the archbishop of Cranganur, which

in turn provoked David *Nieto's scathing rejoinder. At the

Lisbon auto-da-fé of Sept. 24, 1752, 30 men and 27 women were

summoned - all but 12 for Judaizing. In addition to these,

three persons were burned in effigy.

[Earthquake in 1755 - flight

possibilities]

The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 allowed many Conversos, together

with those incarcerated in the dungeons of the Inquisition to

escape, and prompted others to make their way to open

communities overseas. After this, no further Judaizers

suffered in the capital; the last victim of the Lisbon

tribunal was Father Gabriel Malagrida - a Jesuit.

[Christian decree of

emancipation for New Christians in 1773]

The reforms of the Marquês de Pombal put an end to all

juridical differences between Old Christians and New (1773),

and the Conversos of Lisbon disappeared as a separate class

although there were many families who continued to preserve

distinct traces of their Jewish origin.

The Renewed Community.

The close association of Portugal with England, and the

position of Lisbon as an intermediate port between Gibraltar

and England, made it inevitable that a Jewish settlement would

be established in the city as soon as Jews could land with

safety. By the middle of the 18th century, some individuals

had found their way there and began to practice Jewish rites

privately under the security of British protection. Most of

them originated from Gibraltar, though there were some from

North Africa and one or two families direct from England.

In 1801, a small piece of ground was leased for use as a

cemetery. The services rendered to the city by certain Jewish

firms at the time of the famine of 1810 improved their status,

and in 1813, under the auspices of a certain R. Abraham

Dabella, a congregation was formally founded. The condition of

the Jews in Lisbon at this period is unsympathetically

portrayed by George Borrow, in his classical

The Bible in Spain

(1843); while Israel Solomon, an early inhabitant, gives an

intimate glimpse in his memoirs (F.I. Schechter in AJHSP, 25

(1917, 72-73). A little later in the century, two other

synagogues (one of which is still in existence) were founded.

In 1868, the community received official recognition for the

first time. It was, however, recognized as a Jewish "colony",

not "community", and the new synagogue (Shaare Tikvah)

constructed in 1902 was not allowed to bear any external signs

of being a place of worship.

[Complete emancipation for

Jews since 1910 - mostly Sephardim - Ashkenazi Jews from

Eastern Europe - refugees from NS territories]

Complete equality was attained only with the revolution of

1910. Until the outbreak of World War I, the vast majority of

the community were Sephardim, mostly from Gibraltar and North

Africa, and many of them still retained their British

citizenship. Subsequently, however, there was a very large

Ashkenazi influx from Eastern (col. 302)

Europe. During World War II, about 45,000 refugees from Nazi

persecution arrived in Portugal, and passed mainly through

Lisbon, on their way to the free world [[North, Central

and South "America" or also Australia and New Zealand]]. In

Lisbon they were assisted by a relief committee headed by M.

Bensabat *Amzalak and A.D. Esagny.

[[All illegal migration and refugees hiding their religion

emigrating under other nationalities are not mentioned. It can

be admitted that at least the double have passed Lisbon

reaching overseas countries]].

[1945-1970: numbers]

The Jews of Lisbon numbered 400 in 1947, and 2,000 in 1970. In

addition to the two synagogues, there was a school and a

hospital, as well as charitable and educational institutions.

Scholars.

In the Middle Ages, Lisbon did not play a very important part

in Jewish scholarship. The most illustrious scholars

associated with it are the *Ibn Yaḥya family. It was also the

birth place of Isaac Abrabanel, who did much of his literary

work there, while Joseph *Vecinho, Abraham *Zacuto, and other

notable scholars are associated with the city in the period

after the expulsion from Spain.

*Levi b. Ḥabib also passed his early years in Lisbon. Many of

the most illustrious Conversos who attained distinction in the

communities of Amsterdam or elsewhere were also natives of

Lisbon - men like Moses Gideon *Abudiente, *Zacutus Lusitanus

(Abraham Zacuto), Paul de Pina (Reuel *Jesurun), Abraham

Farrar, Duarte Nunes da Costa, Duarte da Silva, and perhaps

*Manasseh Ben Israel.

The outstanding figure in the modern community of Lisbon was

Moses Bensabat Amzalak, who was important in public, economic,

and intellectual life, as well as being a prolific writer on

Jewish subject.

Hebrew Printing.

A Hebrew printing press was active in Lisbon from 1489 to at

least 1492 (see *Incunabula) and was closely connected with

that of *Híjar, Spain, from which it took over the excellent

type, decorated borders, and initials. After 1491 a new type

was used. The founder of the Lisbon press was the learned and

wealthy Eliezer b. Jacob Toledano (in whose house it

operated), assisted by his son Zacheo, Judah Leon Gedaliah,

Joseph Khalfon, and Meir and David ibn *Yaḥya. Their first

production was Naḥmanides' Pentateuch commentary (1489); in

the same year Eleazar Altansi brought out David Abudraham's

prayer book. Other works printed in Lisbon are Joshua b.

Joseph of Tlemcen 's

Halikhot

Olam (1490); the Pentateuch with Onkelos and Rashi in

1491 (text with the vowel and cantillation signs); Isaiah and

Jeremiah with David Kimḥi's commentary 81492); Proverbs with

David ibn Yaḥya's commentary

Kav ve-Naki (1492);

Tur Oraḥ Ḥayyim (also

1492?) and Maimonides'

Hilkhot

Sheḥitah. No other productions have been preserved

apart from a fragment from a Day of Atonement

maḥzor, which may have

come from this press. On the expulsion from Portugal in 1497,

the printers - taking their type, tools, and expertise with

them - found refuge in *Constantinople, *Salonika, and *Fez

where they continued to produce beautiful books.

Bibliography:

-- Roth, marranos, index

-- J. Mendes dos Remédios: The Jews in Portugal (orig.

Portuguese: Os judeus em Portugal), 2 vols. (1895-1928),

index

-- S. Schwarz: Hebrew inscriptions in Portugal (orig.

Portuguese: Inscripções hebraicas em Portugal) (1923)

-- M. B. Amzalak: Hebrew printing in Portugal in 15th

century (orig. Portuguese: Tipographia hebráica em

Portugal no século XV) (1922)

-- M. Kayserling: History of the Jews in Portugal (orig.

German: Geschichte der Juden in Portugal) (1867)

-- J.L. d'Azevedo: História dos Christāos Novos

Portuguêses (1921), index

-- King Manuel (of Portugal: Early Portuguese Books:

1489-1600 (1929), I, 23-43

-- J. Bloch: Early Printing in Spain and Portugal (1938),

32-35

-- B. Friedberg: Toledot ha-Defus ha-Ivri be-Italyah

(1956), 102-4.

[C.R.]>

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia judaica: Jews in Lisbon, vol. 11, col.

299-300

|

Encyclopaedia judaica: Jews in Lisbon, vol. 11, col.

301-302

|

Encyclopaedia judaica: Jews in Lisbon, vol. 11, col.

303

|