<BARCELONA,

Mediterranean port in Aragon, northeastern Spain, seat of

one of the oldest Jewish communities in the country.

[Some spots of the Jewish

community of Barcelona]

*Amram Gaon sent his version of the prayer book to "the

scholars of Barcelona". In 876/7 a Jew named Judah

(Judacot) was the intermediary between the city and the

emperor Charles the Bald. Tenth- and eleventh-century

sources mention Jews owning land in and around the city.

The prominence of Jews in Barcelona is suggested by the

statement of an Arabic chronicler that there were as many

Jews as Christians in the city, but a list of 1079 records

only 60 Jewish names. The book of

Usatges ("Custumal")

of Barcelona (1053-71) defines the Jewish legal status.

Jewish ownership of real estate continued: the site of the

ancient Jewish cemetery is still known as Montjuich. a

number of Jewish tombstones have been preserved. From the

end of the 11th century the Jews lived in a special

quarter in the heart of the old city, near the main gate

and not far from the harbor. The main street of the

quarter is still called Calle del Cal ("The Quarter of the

Kahal").

[Jurisdiction - Jewish

minters in Barcelona - Jewish services for the king -

professions]

Barcelona Jews were subject to the jurisdiction of the

counts of Barcelona. The forms of contract used by Jews

here from an early date formed the basis of the

Sefer ha-Shetarot of

*Judah b. Barzillai al-Bargeloni, written at the beginning

of the 12th century.

In the first half of the 11th century, some Barcelona Jews

(col. 208)

were minters, and coins have been found bearing the name

of the Jewish goldsmith who minted them. In 1104, four

Jews of Barcelona received the monopoly to repatriate

Muslim prisoners of war to southern Spain. Shortly

afterward, *Abraham b. Hiyya was using his mathematical

knowledge in the service of the king of Aragon and the

counts of Barcelona, possibly assisting them to apportion

territories conquered from the Muslims. From the beginning

of the 13th century, the Jewish community provided beds

for the royal retinues on their visits to Barcelona and

looked after the lions in the royal menagerie.

The Jews were mainly occupied as artisans and merchants,

some of them engaging in overseas trade.

Communal Life.

Documents of the second half of the 11th century contain

the first mention of nesi'im ("princes"; see *

nasi) of the house of

Sheshet (see Sheshet b. Isaac *Benveniste), who served the

counts as suppliers of capital, advisers on Muslim

affairs, Arab secretaries, and negotiators. From the

middle of the 12th century the counts would frequently

appoint Jews also as bailiffs (baile) of the treasury;

some of these were also members of the Sheshet family.

Christian anti-Jewish propaganda in Barcelona meanwhile

increased. [[...]]

The bailiff and

mintmaster of Barcelona at the time was Benveniste de

Porta, the last Jew to hold this office.

The Jews were subsequently replaced by Christian burghers;

Jews from families whose ancestors had formerly acquired

wealth in the service of the counts now turned to commerce

and moneylending. However, learned Jews such as Judah

*Bonsenyor continued to perform literary services for the

sovereign.

[[...]]

[Disputations in

Barcelona]

In 1263 a public *disputation was held at Barcelona in

which *Nahmanides confronted *Pablo Christiani in the

presence of James I of Aragon. [[...]]

By the beginning of the 13th century, a number of Jewish

merchants and financiers had become sufficiently

influential to displace the

nesi'im in the conduct of communal

affairs. In 1241, James I granted the Barcelona community

a constitution to be administered by a group of

ne'emanim (

secretarii, or

"administrative officers") - all drawn from among the

wealthy, who were empowered to enforce discipline in

religious and social matters and to try monetary suits.

James further extended the powers of these officials in

1272.

Solomoin b. Abraham *Adret was now rabbi in Barcelona, an

office which he held for about 50 years. Under his

guidance, the Barcelona Jewish community became foremost

in Spain in scholarship, wealth, and public esteem. He and

his sons were among the seven

ne'emanim, and he must have favored the

new constitution.

The ne'emanim did not admit to their number either

intellecutals whose beliefs were suspect or shopkeepers

and artisans. When the controversy over the study of

philosophy was renewed at the end of Adret's life, the

intellectuals of Barcelona did not therefore dare to voice

their opinions. In 1305, Adret prohibited the youth from

studying philosophy under penalty of excommunication: this

provision was also signed by the

ne'emanim and some 30 prominent members

of the community.

[1327: Third constitution

- Jewish refugees from France]

A third constitution was adopted in 1327, by which time

the community had been augmented, in 1306, by 60 families

of French exiles. The privileges, such as exemption from

taxes, enjoyed by Jews close to the court were now

abolished, and, alongside the body of

ne'emanim, legal

status was accorded to the "Council of Thirty", an

institution that had begun to develop early in the 14th

century. The new regulations helped to strengthen the

governing body. Several Spanish communities used this

constitution as a model.

Berurei averot

("magistrates for misdemeanors") were appointed for the

first time in 1338 to punish offenders against religion

and the accepted code of (col. 209)

conduct. In the following year

berurei tevi'ot ("magistrates for

claims") were elected to try monetary suits. The communal

jurisdiction of Barcelona, which at times acted on behalf

of all the communities of Catalonia and Aragon, extended

to several communities, both small and large, including

that of Tarragona.

[Trade restrictions for

the benefit of the Christians - Black Death -

protection]

In the 14th century the monarchy yielded to the demands of

the Christian merchants of Barcelona and restricted Jewish

trade with Egypt and Syria. In addition, the community

suffered severely during the *Black Death of 1348. Most of

the "thirty" and the

ne'emanim

perished in the plague, and the Jewish quarter was

attacked by the mob. Despite protection extended by the

municipality, several Jews were killed.

In December 1354, delegates for the communities of

Catalonia and the province of Valencia convened in

Barcelona with the intention of establishing a national

roof organization for the Jewish communities of the

kingdom in order to rehabilitate them after the

devastations of the plague.

In the second half of the century R. Nissim *Gerondi

restored the yeshivah [[religious Torah school]] of

Barcelona to its former preeminence. Among his disciples

were R. *Isaac b. Sheshet and R. Hasdai *Crescas, both

members of old, esteemed Barcelona families who took part

in the community administration after the late 1360s.

The Decline.

[Defamation of 1367 and

recovery]

Around 1367 the Jews were charged with desecrating the

*Host, several community leaders being among the accused.

Three Jews were put to death, and for three days the

entire community, men, women, and children, were detained

in the synagogue without food. Since they did not confess,

the king ordered their release. However, Nissim Gerondi,

Isaac b. Sheshet, Hasdai Crescas, and several other

dignitaries were imprisoned for a brief period.

The community gradually recovered after these misfortunes.

Jewish goldsmiths, physicians, and merchants were again

employed at court. After Isaac b. Sheshet's departure from

Barcelona and Nissim Gerondi's death, Hasdai Crescas was

almost the sole remaining notable; he led the community

for about 20 years.

[Professions: artisans -

1386: New Jewish charter of professions]

The main element in the (col. 210)

Barcelona community was now the artisans - weavers, dyers,

tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and

coral-workers. These were organized into guilds, and

demanded their share in the communal administration.

After the long period in which the ruling oligarchy had

been exercising their authority to their own advantage,

the 1327 charter was abolished by royal edict in 1386. A

new charter was approved by which representatives of the

two lower estates, the merchants and artisans, shared in

the administration.

[The pogroms and the

massacres of 1391]

During the persecutions of 1391, the city fathers and even

the artisans of Barcelona tried to protect the Jews of the

city, but without success. The violence in Barcelona was

instigated by a band of Castilians, who had taken part in

the massacres in Seville and Valencia and arrived in

Barcelona by boat. News of the onslaught on the Jewish

quarter in Majorca set off the attack on Saturday, August

5. About 100 Jews were killed and a similar number sought

refuge in the "New Castle" in the Jewish quarter. The gate

of the

judería

[[Jewish quarter]] and the notarial archives were set on

fire and looting continued throughout that day and night.

The Castilians were arrested and ten were sentenced to the

gallows.

The following Monday, however, the "little people"

(populus minutus), mostly dock workers and fishermen,

broke down the prison doors and stormed the castle. Many

Jews were killed. At the same time, serfs from the

surrounding countryside attacked the city, burned the

court records of the bailiff, seized the fortress of the

royal vicar, and gave the Jews who had taken refuge there

the alternative of death or conversion.

The plundering and looting continued throughout that week.

Altogether about 400 Jews were killed; the rest were

converted. Only a few of them (including Hasdai Crescas,

whose son was among the martyrs) escaped to the

territories owned by the nobility or to North Africa. At

the end of the year John I condemned 26 of the rioters to

death, but acquitted the rest.

[1393: restored Jewish

rights - prohibition of Jewish community in 1401]

In 1393 John took measures to rehabilitate the Jewish

community in Barcelona. He allotted the Jews a new

residential quarter and ordered the return of the old

cemetery. All their former privileges were restored and a

tax exemption was granted (col. 211)

for a certain period, as well as a moratorium on debts.

Hasdai was authorized to transfer Jews from other places

to resettle Barcelona, but only a few were willing to

move. Reestablishment of a Jewish community in Barcelona

was finally prohibited in 1401 by Martin I in response to

the request of the burgers.

The Conversos.

[Inquisition - emigration

of the rich Jews - crisis of the town]

The renewed prosperity of Barcelona during the 15th

century should be credited in part to the Conversos, who

developed wide-ranging commercial and industrial

activities. Despite protests by the city fathers, in 1486

Ferdinand decided to introduce the Inquisition on the

Castilian model in Barcelona. At the outset of the

discussions on procedure the Conversos began to withdraw

their deposits from the municipal bank and to leave the

city. The most prosperous merchants fled, credit and

commerce declined, the artisans also suffered, and

economic disaster threatened. The inquisitors entered

Barcelona in July 1487. Some ships with refugees on board

were detained in the harbor. Subsequently several

high-ranking officials of Converso descent were charged

with observing Jewish religious rites and put to death. In

1492 many of the Jews expelled from Aragon embarked from

Barcelona on their way abroad.

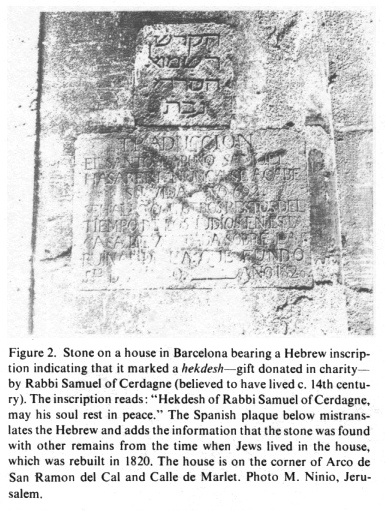

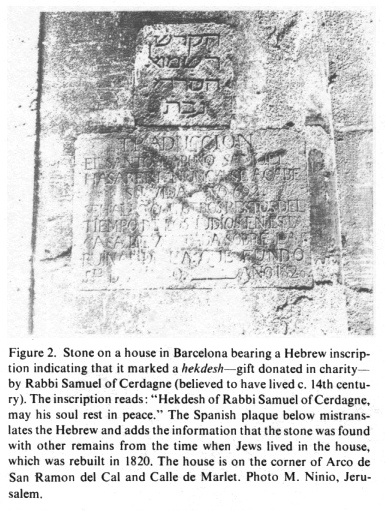

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Barcelona, vol. 4, col.

211, inscription in a wall stone, 1820

At the beginning of the 20th century a few Jewish peddlers

from Morocco and Turkey settled in Barcelona. After the

conquest of Salonika by the Greeks in 1912 and the

announcement by the Spanish government of its willingness

to encourage settlement of Spanish Jews on its territory

(1931), Jews from Greece and from other Balkan countries

migrated to Barcelona. Other Jews arrived from Poland

during World War I, followed by immigrants from North

Africa, and by artisans - tailors, cobblers, and hatmakers

- from Poland and Rumania [[Romania]]. There were over 100

Jews in Barcelona in 1918, while in 1932 the figure had

risen to more than 3,000, mostly of Sephardi origin.

After 1933 some German Jews established ribbon, leather,

and (col. 212)

candy industries. By 1935 Barcelona Jewry numbered over

5,000, the Sephardim by now being a minority. During the

Spanish Civil War (1936-39), many left for France and

Palestine. Some of the German Jews left the city after the

Republican defeat in 1939, but during and after World War

II Barcelona served as a center for refugees, maintained

by the *American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and

others returned to resettle.

The Barcelona community, consisting of approximately 3,000

people in 1968, is the best organized in Spain. The

communal organization unites both Sephardi and Ashkenazi

synagogues. There is also a community center, which

includes a rabbinical office and cultural center. The

community runs Jewish Sunday schools for children

attending secular schools, and has a

talmud torah. Youth

activities include summer camps and a growing Maccabi

movement. An old-age home supported by Jewish agencies

outside Spain is maintained. The University of Barcelona

offers courses in Jewish studies. Together with leaders of

the Madrid community, Barcelona community heads were

received in 1965 by General Franco, the first meeting

between a Spanish head of state and Jewish leaders since

1492.

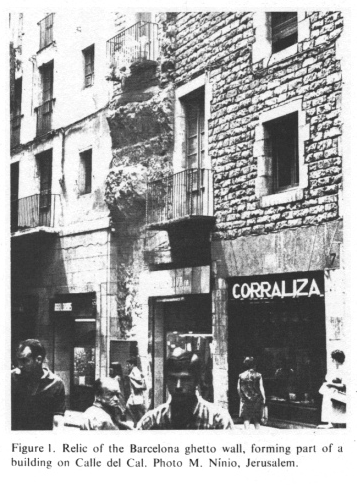

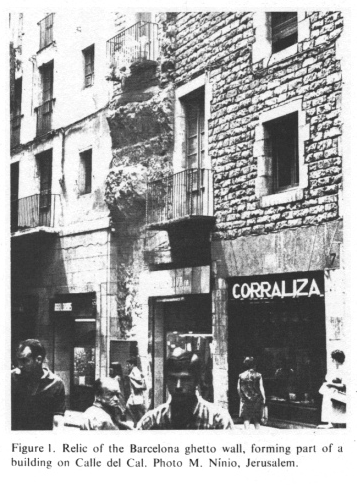

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Barcelona, vol. 4, col.

210, rest of ghetto wall in Calle del Cal