Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in South Africa 04: Communal structures

Synagogues - board of deputies - Jewish religious institutions - Jewish charity institutions - integration of immigrants and women work

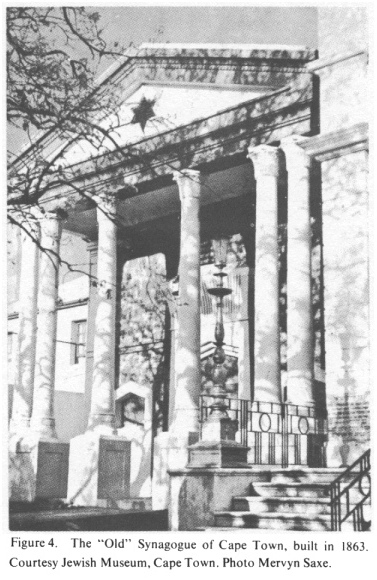

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol.15, col.192: The "Old" Synagogue of Cape Town, built in 1863.

Courtesy Jewish Museum, Cape Town. Photo: Mervyn Saxe.

from: South Africa; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 15

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2010 / 2020)

| Share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<Communal Organization and Structure.

HISTORICAL SURVEY.

The earliest pattern of communal organization was established by Jews of German, English, and Dutch extraction. Their congregations provided elementary facilities for worship, classes for Hebrew and religious instruction of the young, and philanthropic aid, and also attended to the rites for the dead. The authority of the chief rabbi of England was accepted in ecclesiastical matters. Joel Rabinowitz (officiated 1859-82), Abraham Frederick *Ornstein, and Alfred P. *Bender (1895-1937), all of whom administered to the Cape Town Congregation, and Samuel I. Rapaport (1872-95), the minister in Port Elizabeth, all emigrated from England.

[English and East European Jewish synagogues]

By the end of the 19th century or soon after, the "greener" East Europeans had broken away from the "English" synagogues in most communities to form their own congregations. Their parochial loyalties were reflected in the many separate associations for religious worship and talmudic study and the numerous *Landsmannschaften (fraternal associations) of persons who had come from the same town or village in Lithuania or Poland. Leading rabbinical personalities in this formative period were: in Johannesburg, Judah Loeb *Landau (officiated 1903-42), from Galicia; the more "Westernized" Joseph Herman *Hertz (1898-1911) who arrived via the United States (he later became chief rabbi of the British Empire); Mowhal Friedman (beginning in 1891), from Lithuania; and L.I. *Rabinowitz (1945-61); and in the Cape, M.Ch. Mirvish (d. 1947), also from Lithuania and I. *Abrahams (1937-68). In lay matters, Jews of English and German origin usually took the lead, but East Europeans also began to assert their influence.

The communal structure gradually underwent change in response to the new social forces - the slowing down of immigration, increasing acculturation and growing homogeneity. Splinter congregations rejoined the older synagogues or new amalgamations took place.

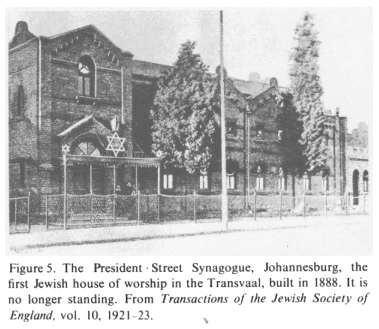

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 194: The President Street Synagogue, Johannesburg, the first Jewish house of worship in the Transvaal, built in 1888. It is no longer standing. From: Transactions of the Jewish Society of England, vol. 10, 1921-23

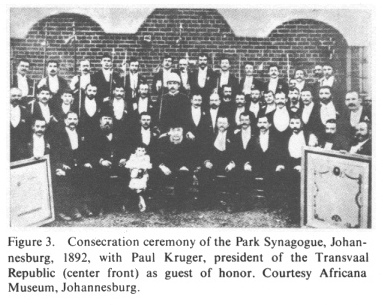

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 191: Consecration ceremony of the Park Synagogue, Johannesburg, 1892, with Paul Kruger, president of the transvaal Republic (center front) as guest of honor. Courtesy Africana Museum, Johannesburg

[By 1940s: new structures in the communities with Zionist, philanthropic and sports groups]

By the 1940s most of the Landsmannschaften had disappeared or (col. 191)

continued to survive on nostalgic memories. Emerging social and cultural needs called forth a variety of new institutions, such as the lodges of the Hebrew Order of David, the Zionist and *Young Israel Societies, the branches of the Union of Jewish Women, the *B'nai B'rith Lodges, the Ex-Servicemen's organizations, the *Reform movement in religious life, and the Jewish social and sports clubs.

Increased communal cohesion began to be reflected in the organizational structure of education, congregational affairs and philanthropy, and overall communal representation. However, older forms of organization, inherited or adapted from the East European tradition, yielded slowly to change. The most striking exceptions were in the Hebrew educational sphere and in the proliferation of Jewish sports clubs.

[1970: Jewish communities: Witwatersrand-Pretoria and Cape Peninsula]

The main concentration of Jewish communities is now in two areas: the Witwatersrand-Pretoria complex in the north, and the Cape Peninsula in the south, where 60% and 23% respectively of the Jewish population now live. Because of the geographic distance and differences of outlook, the regional bodies in the south maintained virtually autonomous religious and educational organizations parallel to the national bodies up north. However, the trend has been toward greater coordination and unity. All the major national Jewish bodies have their headquarters in Johannesburg, which has now become the focal point of Jewish life.

SOUTH AFRICAN JEWISH BOARD OF DEPUTIES.

[Jewish Boards of Deputies for Transvaal (1903) and for the Cape (1904) - unification to the South African Board of Deputies in 1912]

A single representative organization, the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, is recognized by Jews and non-Jews alike as the authorized spokesman for the community. It is charged with safeguarding the equal rights and status of Jews as citizens and generally protecting Jewish interests. A Board for the Transvaal was formed in 1903, on the initiative of Max *Langerman and Rabbi Joseph Hertz, (col. 192)

with the encouragement of the High Commissioner, Lord *Milner, and was named after its prototype in England. At first it encountered opposition from the Zionists. Among its early leaders were Bernard *Alexander, Manfred *Nathan, and Siegfried Raphaely. An independent Board for the Cape was formed in 1904 through the efforts of Morris *Alexander and David Goldblatt, despite opposition from the Rev. Alfred P. Bender and his congregation.

Following the unification of the four provinces in 1910, the two bodies were unified in the South African Board of Deputies (1912).

[1912-1970: Activities of the South African Board of Deputies against anti-Semitism and help for Jewish war victims - chairmen and activities]

Its main concern was to prevent discrimination against Jews in respect of immigration and naturalization, and to rebut defamatory attacks on Jews. It led the community's efforts in rendering relief to Jews in Europe after World War I, and later was active also on behalf of German Jewry and the displaced persons of World War II through the instrumentality of the South African Jewish Appeal (1942).

A relatively small and weak body, the Board underwent reorganization in the early 1930s to meet the challenge of Nazism and anti-Semitism. While Johannesburg remained the headquarters, provincial committees were set up in Cape Town - the seat of Parliament - Durban, Port Elizabeth, and Bloemfontein. The position of chairman of the executive council was held by Cecil Lyons (1935-40); Gerald N. Lazarus (1940-45); Simon M. Kuper (1945-49); Israel A. *Maisels (1949-51); Edel J. Horwitz (1951-55); Namie Philips (1955-60); Teddy Schneider (1960-65); Maurice Porter (1965-1970); and David Mann (from 1970).

Its secretary and later general secretary for many years was Gustav Saron. J.M. Rich and L. Druion also served the Board for many years as secretary and assistant secretary respectively.

The Board's membership consisted in 1969 of 330 organizations which include all types of institutions.

As new needs had to be met, the Board became a functional agency in various fields. It promotes adult education, publishes a monthly Jewish Affairs, and maintains in Johannesburg a museum of Jewish religious art and Jewish Africana, and a library of Jewish information and archives relating to South African Jewry. It serves unaffiliated youth through its youth department (emphasizing youth leadership training), and promotes a program for Jewish students (jointly with the Zionist Federation). There is frequent consultation and cooperation between the Board and the Zionist Federation. South African Jewry has not favored the establishment of United Jewish Appeals to combine in one campaign the needs of Israel, overseas relief, and local and national institutions.

In 1949 the Board launched the United Communal Fund for South African Jewry, which provides the budgets - in whole or in part - of the Board itself, and of its 17 other national and semi-national organizations active in the spheres of education, religion, youth, and student work, and related interests. While there is a tendency for institutions in South Africa to function in "watertight" compartments, conditions are somewhat better at the local level, as exemplified in the "united institutions" which exist in some towns. There is a growing awareness of the need for more overall planning and coordination.

RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS.

[Orthodox Jewish congregations - youth synagogues - progressive movement]

The great majority of Hebrew congregations subscribe to Orthodox Judaism. The Reform or Progressive movement has established congregations in all the larger urban centers. In 1966, there were in Johannesburg 29 Orthodox congregations and four Reform temples; and in Cape Town, 12 Orthodox congregations and two Reform temples. Most congregations, Reform as well as Orthodox, maintain Hebrew religious talmud torah classes, and sometimes also nursery schools. They provide facilities for youth groups and some have separate youth synagogues. Ladies' guilds (sisterhoods as they are named (col. 193)

by Reform) carry out cultural and social programs among women members. The Progressive movement possesses two permanent holiday camps. The Federation of Synagogues of South Africa, established as a Johannesburg body in 1933, has affiliated to it most congregations in the Transvaal, Natal, Orange Free State, and Eastern Province of the Cape. Those in the Cape (Western) Province and South-West Africa are associated together in the United Council of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations (with headquarters in Cape Town), which is developing a closer relationship with the Federation.

Each of these bodies maintains its chief rabbinate and ecclesiastical court (bet din), the latter dealing with conversions to the Jewish faith, the issuance of divorces, supervision of kashrut [[Jewish food laws]], and similar matters. Although the Federation established and maintains the bet din, and also appoints the dayyanim [[judges]], the bet din is an independent body, exercising supreme plenary authority in Orthodox religious matters. The Federation publishes a monthly journal and has a youth department, which coordinates the youth activities of the various synagogues.

The Progressive congregations are associated together in the South African Union for Progressive Judaism, religious issues being handled by a central ecclesiastical board. The latter consists of rabbis and a few laymen, with a rabbi elected annually as its chairman. The ladies guilds in Orthodox synagogues are affiliated to the Federation of Synagogues' Ladies Guilds, and the Reform sisterhoods to the National Union of Temple Sisterhoods.

[Special associations and education institutions]

There is an Orthodox Rabbinical Association of South Africa, its members being drawn from the clergy of all parts of the country, other than Cape Province, which has its own body, Omer.

A small college for the training of ministers, rabbis, and shohatim [[ritual slaughterers]], established in Johannesburg initially under the auspices of the Federation of Synagogues, and subsequently supported by the United Communal Fund, has trained a number of students for serving in various congregations.

For the provision of religious and educational facilities for the small rural communities - many of them unable to maintain their own minister or teacher - there was established in 1951 a National Country Communities Committee. It functions within the framework of the South African Jewish Board of Deputies (in association with the bet din [[ecclesiastical court]], the Federation of Synagogues and the Board of Jewish Education), and is headed by the rabbi to the Country Communities, who pays periodic visits to the rural communities.

Chaplaincy services to Jewish men in the armed forces are provided by the Chaplaincy Committee, composed of representatives of the Board of Deputies, the (col. 194)

Federation of Synagogues, the Union of Progressive Judaism, the Jewish Ex-Servicemen's organization, the Union of Jewish Women, and the Rabbinical Association. The chaplains are usually ministers or rabbis serving communities in the areas where military camps are located. Most of the administrative work of the Chaplaincy Committee is carried out by the Board of Deputies. There were 30 Jewish chaplains serving in the field in World War II.

PHILANTHROPY.

[Jewish charity institutions in South Africa]

Institutions to assist the poor and needy early became an established feature of communal organization. In the wake more particularly of the East European immigration, there was a proliferation of many kinds of philanthropic institutions or fraternal bodies having philanthropic objects, such as Landsmannschaften, free-loan societies, societies to visit the sick, and especially for the provision of financial and material help to those in need. Many of these institutions bore the hallmark and followed the methods of East European traditions of zedakah [[justice, charity]]. (For instance, the largest welfare body in Johannesburg, the hevra kaddisha, combines extensive philanthropic work with the activities of a burial society). The organizational structure and also the underlying principles of Jewish social welfare subsequently underwent changes under the impact of changing social conditions.

The largest charitable agencies in Johannesburg are the Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society - the hevra kaddisha (founded in 1880), Jewish Women's Benevolent and Welfare Society (1893), Witwatersrand Hebrew Benevolent Association, a free-loan society (1893), South African Jewish Orphanage, Arcadia (1903); Witwatersrand Jewish Aged Home (1911), Our Parents Home (1940); and the Selwyn Segal Home for Jewish Handicapped (1959).

Leading bodies in the Cape include the Cape Jewish Board of Guardians (1859), the Cape Jewish Aged Home (1918), and the Cape Jewish Orphanage "Oranjia" (1911). The Jewish community has assumed financial responsibility for all its welfare needs, the large budgets being met by fees, membership dues, contributions, and bequests. Some advantage has been taken of government grants for specific welfare projects. The establishment of the Transvaal Jewish Welfare Council (1946) marked a step toward greater coordination and a more modern approach. This council, embracing only the Transvaal, but aspiring to become countrywide, acts as a coordinating body. Its 24 affiliates include the main welfare organizations in the Witwatersrand.

FRATERNAL ORGANIZATIONS.

[Integration work for the immigrant generation]

In the first decades of the 20th century many of the communal organizations provided some form of philanthropic and fraternal services to assist the integration of the immigrant generation. As late as 1929, of the 68 Jewish institutions in Johannesburg then affiliated to the Board of Deputies, 38 were either wholly or partly philanthropic. An indigenous South African institution of this type, the Hebrew Order of David, founded successive lodges after 1904 and, as members began to be recruited among the South African-born generation, added social, cultural, and communal objectives. The Grand Lodge has its headquarters in Johannesburg.

UNION OF JEWISH WOMEN.

[since 1931 / 1936: Union of Jewish Women serving all sections of the population]

In the women's sphere the Union of Jewish Women of South Africa plays a major role. The first branch was formed in Johannesburg in 1931 and a national body in 1936. In 1969 the Union had 64 branches throughout the republic with a total membership of between 9,000 and 10,000 women, its national headquarters being in Johannesburg. The Union maintains a wide range of activities and acts as a coordinating body for Jewish women's organizations. A distinctive aspect of its program is its undenominational work, educational and (col. 195)

philanthropic, serving all sections of the population. Some branches run creches and feeding depots for indigent colored and African children and adults. Branches of the Union have established Hebrew nursery schools, friendship clubs, services for the aged, youth projects, and a wide program of adult education. The Union is also closely associated with the women's division of the United Communal Fund, which functions under its auspices.> (col. 196)

^