Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in South Africa 05: Community life

Religious developments - Yiddish decline - Jews between English and Afrikaans

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 185: Record of the first minyan [[group of 10 Jewish men for religious services]]

assembled in South Africa. It met in a private house in Cape Town, Cape of Good Hope, on the Day of Atonement, 1841.

From L. Herman: History of the Jews of South Africa, 1935. Photo A. Elliott, Cape Town.

from: South Africa; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 15

presented by Michael Palomino (2008 / 2010 / 2020)

| Share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<Social and Cultural Life.

INFLUENCE OF IMMIGRATION STREAMS.

Following the congregational beginnings in Cape Town in 1841, loss of identity through assimilation was gradually arrested, although the immigrants became quickly integrated into the general economic and cultural life. In secular matters, as also in religious, they maintained ties with Anglo-Jewry, and this tradition was followed also by the immigrants from Germany. The latter, socially influential, often assumed the leadership, but do not appear to have made a specifically German-Jewish cultural contribution.

[Religious differences between English, German and East European Jewish immigrants - the young generation gets over the differences]

The growing numbers of East Europeans led in time to social, religious, and cultural ferment. Social distance, and even open friction and conflict, developed between the "greeners" and the older sections, due to differences in ritual tradition, in intensity of religious observance, or in attitudes to Jewish education and Zionism. Nonetheless, many aspects of the Anglo-Jewish pattern persisted, although it underwent changes in spirit and content.

Elements of the legacy of Lithuanian Jewry may be identified in certain characteristics of South African Jewry: generous support for all philanthropic endeavors, respect for Jewish scholarship and learning, exemplified in the status accorded to the rabbinate and concern for Jewish education; and a conservative outlook toward religious observance (at least in externals).

However, as the community became largely South African-born and homogeneous, the barriers that formerly separated the various immigrant groups all but disappeared.> (col. 197)

<RELIGION.

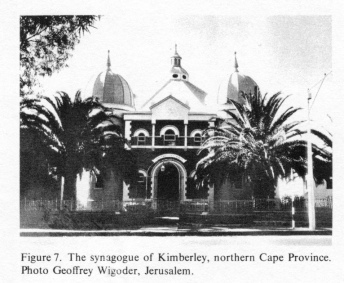

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 199: The synagogue of Kimberley,

northern Cape Province. Photo: Geoffrey Wigoder, Jerusalem

Apart from the Zionist Movement, the synagogue and the Hebrew congregation - as symbolizing formal identification with Judaism and Jewish life - continue to occupy a central place, even though synagogue membership may sometimes denote little personal commitment to the tenets and practices of the Jewish religion. There is some evidence of an increased interest in the synagogue among younger people, especially those affiliated to the Benei Akiva and other Orthodox youth groups, but its strength can only be conjectured.

[Orthodox groups - pro-Zionist racist anti-Muslim Reform movement]

The majority of the Hebrew congregations describe themselves as "Orthodox" and follow traditional practices in their mode of worship. The Conservative movement as known in America dose not exist in South Africa, although many members of nominally Orthodox congregations would probably subscribe to Conservative principles and practices. The Reform (Progressive) movement was started in South Africa in 1933 by Rabbi Moses Cyrus Weiler (1907- ) of the United States and was later led by Rabbi Arthur Saul Super (1908- ) in the teeth of strong Orthodox opposition.

The Reform movement became established, especially in the larger communities, and claims support from about 20% of the whole Jewish population. In South Africa Reform avoided some of the radical manifestations of the American movement, and has always been strongly pro-Zionist. In contrast to the Orthodox synagogues, which confined their activities largely within the Jewish community, Reform congregations broke new ground by adopting programs for Christian-Jewish goodwill and by fostering social welfare projects among non-whites, particularly for children.

Both Orthodox and Reform congregations had difficulties in finding rabbis and ministers. The sources in Europe which provided them with trained and experienced ministers no longer existed. South African-born candidates for the ministry received training in South Africa itself, while others studied in England, Israel, or the United States.> (col. 200)

[[It seems that the Zionists had such a strong propaganda that to be a non-Zionists would have meant to be excluded from the community]].

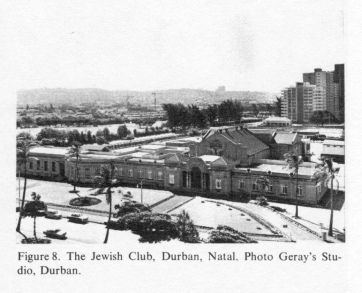

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 204: The Jewish Club, Durban, Natal. Photo: Geray's Studio, Durban

[Languages: The "older generation" and the Yiddish decline]

The older generation still plays a part in communal affairs but the leadership largely passed to South Africans. The Yiddish language, the only vernacular used by the East European immigrants, became confined to a small minority. (In the 1936 census, 17,861 persons declared Yiddish as their home language; by 1946 the figure was 14,044, and in 1951, it had fallen to 9,970. In 1960, of the large Jewish population in Johannesburg, only 2,786 declared Yiddish to be their home language).

Table. Yiddish in South Africa

Year

number of speakers

remarks

xxxxx1936xxxxx

17,861xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

1946

14,044xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

1951

9,970xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

1960

2,786xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx only Johannesburg Table by Michael Palomino; from: South Africa; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 15, col. 197

FORCES STRENGTHENING GROUP IDENTITY.

[Rise in the material conditions - Jewish group life between English and Afrikaans]

The normal trends of acculturation and integration - linguistic, cultural, and economic - were accelerated by the rapid rise in the material condition of many Jews. Although reliable statistics are not available, the incidence of extra-faith marriages is apparently increasing. However, South African Jewry has thus far escaped large-scale manifestations of assimilation and maintains a vigorous group life. Various factors have contributed to this.

The influence of the immigrant generation is still felt to some extent. The country's cultural and political climate, which emphasizes the distinctiveness of the various linguistic, cultural, and ethnic groups of the population, and especially the coexistence of the English and Afrikaans language and culture, partly in rivalry, have been favorable to the preservation of a separate Jewish group life. There was no pressure upon the Jew to drop his identity or to become an "unhyphenated" South African.> (col. 197)

^

![Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa, vol. 15, col. 185:

Record of the first minyan [[group of 10 Jewish men for

religious services]] assembled in South Africa. It met

in a private house in Cape Town, Cape of Good Hope, on

the Day of Atonement, 1841. From L. Herman: History of

the Jews of South Africa, 1935. Photo A. Elliott, Cape

Town. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Jews in South Africa,

vol. 15, col. 185: Record of the first minyan [[group of

10 Jewish men for religious services]] assembled in

South Africa. It met in a private house in Cape Town,

Cape of Good Hope, on the Day of Atonement, 1841. From

L. Herman: History of the Jews of South Africa, 1935.

Photo A. Elliott, Cape Town.](../d/EncJud_juden-in-suedafrika-d/EncJud_South-Africa-band15-kolonne185-minyan1841.jpg)