Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in the "USA" 08: 1945-1970

Racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel - anti-Semitism in clubs and management - numbers - further immigration - community - professions - collections - schooling - English writing - "third religion" - attendance questions - new Jewish law - Vatican 1965 - Jews and Blacks for civil rights - Six-Day War

zu den Meldungen

from: Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): USA; Vol. 15

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

[Collaboration of the Jews of the "USA" with racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel 1945-1950]

During the five years following the war's end in 1945, U.S. Jewish communal life was dominated by developments among Jewish refugees in Europe, and by the Jewish struggle in Palestine [[by the racist Jewish army raping and murdering around]]. Vast public meetings were frequently convened, while gentile political and religious leaders were won over by persuasion or pressure, and funds raised for overseas needs reached levels previously unknown. Thus the *Zionist Organization of America (Z.O.A.) raised its membership from 49,000 in 1940 to 225,000 in 1948, while *Hadassah numbering 81,000 in 1940, multiplied more than threefold. As the U.S. exercised a dominant position in international affairs, [[racist]] U.S. Zionist leaders became important in framing [[racist]] world Zionist policy, and tended to take a somewhat more militant position than the Palestinian leadership. Several thousand U.S. Jewish volunteers navigated the "illegal" immigrant ships across the Mediterranean and fought in Palestine in 1948-49. With the founding of the [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] State of Israel in 1948 and its War of Independence until 1949, U.S. Jewish interest reached a peak which quickly declined. Membership in [[racist]] Zionist organizations dropped drastically, in the case of the Z.O.A. beneath 25,000 in the mid-1950s, and monies raised, as well as the proportion of them actually allocated to [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel, slid slowly downward. Yet the development of [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel became a philanthropic, political, and, to some extent, cultural interest of U.S. Jewry as a whole.

[Jewish soldiers from WW II coming back]

In common with U.S. citizens generally, Jews enjoyed an era of prolonged prosperity during the post-World War II years. Homecoming soldiers found jobs or attended college en masse under the liberal terms of the "GI Bill of Rights".

[Anti-Semitism in clubs and management]

Anti-Semitism in the United States all but disappeared from public view. Father Coughlin had been (col. 1635)

silenced by his church, and a few agitators, notably G.L.K. Smith, were practically ignored. Active and largely successful efforts were made by the U.S. Jewish defense organizations to root out anti-Semitic and every other form of religious and racial discrimination in employment, housing, and higher education. Legislation to these ends in many states was spearheaded by the Jewish community, often in alliance with such Negro bodies as the N.A.A.C.P. and the Urban League, and church organizations.

On the other hand, efforts to eliminate the exclusion of Jews from upper-level social clubs and from the management of major banks and corporations proved less successful [[see also: *Discrimination]].

The basic trend for two decades following the end of World War II was the decline of anti-Semitism to the point where its disappearance was widely predicted. Even the feverish atmosphere of the anti-Communist fright from about 1947 to 1954 and the hunt for alleged Communists in government and strategic positions, during which a high proportion of the accused were Jews, did not significantly stir anti-Semitic sentiment. (col. 1636)

[[More details]]:

After 1945 anti-Semitism in the United States did not assume the ideological strength it had achieved in the preceding decades. Direct anti-Jewish agitation after World War II was limited, for the most part, to isolated fringe groups which were declining in number. Among the active exponents of anti-Semitism were such individuals and groups as the Columbians, the miniscule but vociferous American Nazi Party, the National Renaissance Party, and such publications as Gerald L.K. Smith's The Cross and the Flag and Conde McGinley's Common Sense. Much more threatening from the Jewish viewpoint were the persistence and growth of ultraconservative groups which officially denied anti-Semitic proclivities but provided a rallying point for many who were anti-Semitically inclined. Significantly, however, the anti-Communist crusade initiated by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the early 1950s, while receiving widespread popular support, never attacked Jews as such.

[[McCarthy also was one of the hardest racists barring Blacks from their rights as also did "President" Eisenhower. Such racism was legal in the criminal "USA", although the Blacks had fought in the army 1941-1945]].

Political anti-Semitism has shown few signs of strength in the post-World War II period and there have been only sporadic anti-Semitic episodes. There has been a noticeable decline in the system of social discrimination elaborated in the United States between 1880 and 1940. American Jewry in the 1950s and 1960s attained a high degree of behavioral acculturation, economic affluence, and educational achievement. The declining "visibility" of Jews, their absorption into the dominant middle-class suburban society, the disreputability of openly avowed prejudice, continued economic prosperity, and the role of government in fostering major civil rights legislation have combined to produce a diminution in social anti-Semitism.

In 1945 the president of Dartmouth College openly admitted and defended a quota system against Jewish students; 20 years later Jewish students comprised 25% of the student body at the prestigious Ivy League universities. (col. 1656)

POPULATION, DEMOGRAPHY, AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY.

[Numbers - further Jewish immigration to criminal racist "USA"]

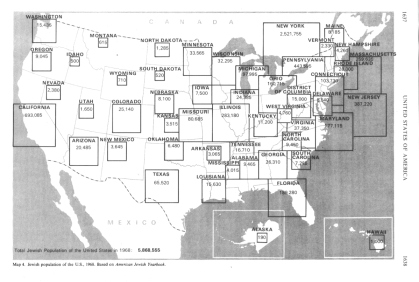

The number of U.S. Jews increased rather slightly. Unfortunately Jewish population estimates, while comparatively accurate for many cities, were unreliable for the country as a whole. The Jewish population, probably overestimated at 5,000,000 in 1945, stood around 5,200,000 in 1956, and by a better based calculation, 5,869,000 in 1969. In comparison, the U.S. population was 140,000,000 in 1945 and over 200,000,000 in 1970.

Immigration provided little of the Jewish increase. From 1944 through 1959, 191,693 Jews settled in the United States, of whom 119,373 arrived from 1947 through 1951. The large majority were European survivors, over 63,000 of whom entered under the provisions of the Displaced Persons Act of 1949. Otherwise, the quota system of the Johnson Act and its successor McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 remained intact until practically abolished by new legislation in 1965. From 1960 through 1968 about 73,000 Jewish immigrants arrived. Jewish immigrants after 1957 tended to be Israelis (frequently of European birth), Cubans leaving the Castro regime, and Near Easterners. The United Service for New Americans, a descendant of the previous National Refugee Service together with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), and local community organizations aided the immigrants. Some "new Americans" were professionally trained, but most tended to enter traditional Jewish occupations, such as garment cutters, salesmen, or shopkeepers. Due to their comparatively small numbers and the stabilization of U.S. Judaism, the influence of post-1945 immigration on Jewish life was small except in Orthodox circles.

[[Addition: Secret Jewish immigration is not mentioned

The immigration with changed name or changed religion with forged documents is not mentioned. But it can be admitted that this kind of secret Jewish immigration was not so rare because it is tradition for persecuted people to hide their identity and forged documents were easy to have by Jewish organizations. It can be that the real immigration is the double of the indicated immigration number of 191,693, this would be approx. 380,000]].

[Community life 1945-1970: centers and new centers of Los Angeles and Miami]

U.S. Jewry continued to be a metropolitan group. About 40% dwelled in the New York City area, as had been the case since 1900; the sum total of Jews living in Greater New York, northeastern New Jersey, and the nine next largest communities (Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Miami, Washington, Cleveland, Baltimore, Detroit) equaled 75% of U.S. Jewry. The most notable demographic phenomenon within these and other urban centers was movement to the suburbs, which to some extent merely continued the usual trend to better neighborhoods as income and aspirations rose. Seeking greater space, more (col. 1636)

relaxed living, and a more homogeneous social environment, large numbers of Jews quit the ever more congested and aging cities. By 1958, 85% of Cleveland Jews lived beyond the city boundaries, and the same happened to virtually the entire Jewish population in Detroit, Newark, and Washington, D.C., within the next decade. Every large city saw a considerable proportion of its middle class, including Jews, settle in the suburbs, especially as massive Negro immigration precipitated formidable social problems. Jewish neighborhoods tended to become Negro rather quickly, except in New York where the process was a slow one.

Coincidental with the suburban movement, was the migration of large numbers of Jews within the United States. The increase of the Los Angels Jewish population from 150,000 in 1945 to 510,000 in 1968, and of Miami from 7,500 in 1937 to 40,000 in 1948 and perhaps 150,000 in 1970, was almost wholly the result of internal migration. Much of it came from the Middle West whose Jewish population failed to increase after the 1920. Thus, Chicago, with 333,000 in the city in 1946, actually declined to 285,000 for its metropolitan area by 1969. Milwaukee also lost - 30,000 to 24,500 - and centers such as Cleveland and Detroit did not increase. Boston's Jewish population increased from 137,000 in 1948 to 176,000 in 1968, apparently owing to heavy Jewish participation in that area's scientific and technological growth.

[Professions 1945-1970]

After 1945 a new occupational pattern of U.S. Jewry became evident. No nationwide survey was conducted but many studies of individual communities made clear that employment in the professions was rising greatly, and proprietorship and management somewhat less so; skilled, semiskilled, and unskilled labor was sharply decreasing, and clerical and sales employment somewhat declining. Forestry, mining, and transportation in all forms hardly employed any Jews, as in the past; the small contingent of Jewish farmers slowly decreased in size. The ascent of the professionals was a general phenomenon. Thus, in the small, venerable Jewish community of Charleston, to which few immigrants came, professionals more than quadrupled between the mid-1930s and 1948. Charleston's antithesis, Los Angeles, likewise saw its Jewish professionals increase from 11% to 25% of heads of household between 1941 and 1959. In addition to the continuing prominence of Jews as physicians, lawyers, accountants, and (in New York City) teachers, they were prominent as scientific professionals in such new industries as electronics.

Earlier occupational patterns lasted longer in New York City where skilled and unskilled workers comprised about 25% of the Jewish labor force in 1952 and in 1961, and professionals only 17% in both years. In such professions as law, medicine, dentistry, and teaching Jews formed a clear majority of those employed. Industries in which they had once been the labor force, especially garments, remained Jewish only at the higher levels of skill and in entrepreneurship. As entrepreneurs, Jews were extensively represented in urban retail trade, the building of homes and shopping centers, and in metropolitan real estate. The same could be said of such mass media areas as television, films, and advertising, and of cultural enterprises like book publishing, art dealing, and impresarioship in music and theater. Stockbrokerage and other spheres of finance continued to involve Jewish firms and brokers, but the high prominence of Jewish financiers during the late 19th and early 20th centuries did not return.

Various local studies showed that around 1960 some 25% of employed Jews were in professional and semiprofessional occupations (as was 13.9% of the employed U.S. population), and 30% were proprietors, managers, or self-employed (col. 1639)

businessmen (as was 10.7% of the employed U.S. population). The proportion in business was especially high in smaller cities, where Jews continued in their old role as leading local merchants. The "clerical and sales" classification included about 25%, and of the remaining 20% about three-quarters were skilled and semiskilled workers and craftsmen, and the small remainder worked at unskilled and manual labor and personal service. Local surveys demonstrated also that the proportion of professionals was higher in the younger Jewish strata. This finding when combined with the fact that some 80% of Jewish youth of college age during the 1960s actually attended college, strongly suggested that the proportion of professionals would continue to rise. In these vocational trends, U.S. Jews anticipated the movement of employment away from manual, craft, agricultural, and factory work into clerical, technical, managerial, and professional occupations. Their attachment to independent entrepreneurship in a corporate age was unique, however. Somewhat scantier evidence indicated that Jewish incomes stood appreciably higher than those of any other religious or ethnic group in the United States. (col. 1640) [[...]]

Discrimination in admission to medical schools is no longer openly practiced and Jewish students increasingly choose careers in such fields as engineering, which in the 1930s were highly discriminatory. In the late 1960s Jewish professors constituted over 10% of the faculties in the nation's senior colleges. Surveys of discrimination by city and country clubs and by resorts have shown a decline in the proportion excluding Jews. Nevertheless, subtle forms of social anti-Semitism persist, especially in what has come to be known as "executive suite" discrimination. While Jews constituted 8% of the college-trained population in the United States, they comprised less than 1/2 % of the executives of America's major companies or presidents of American colleges. (col. 1656)

Despite conflicting evidence, public-opinion surveys which were conducted in the U.S. during the period from 1940 to 1970 (col. 1656)

generally documented a substantial decline in anti-Semitic attitudes. Whereas 63% of the American public attributed *objectionable traits" to the Jews as a group in 1940, only 22% felt this way in 1962. Anti-Semitism in the United States, while far from extinct, is usually no longer expressed openly. The American political system has acted as a brake on anti-Semitism and the civil position of Jews in the United States has never been fundamentally endangered. Nevertheless, latent anti-Jewish stereotypes are persistent. (col. 1657)

STATUS AND COMMUNAL STRUCTURE.

[Racist Zionist manipulation with fund raising for racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel - local matters - combined collections for overseas and domestic needs - unifications]

Economic prosperity, the neutralization of once sharp ideological differences, growing social homogeneity, and the closing of the rift between natives and immigrants resulted in a lengthy period of communal consensus which perhaps extended from 1950 to 1968. The [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] State of Israel became a unifying rather than divisive force. Funds were ample for generally agreed communal purposes in the United States and overseas. A benevolent neutrality prevailed upon religion, except in some Orthodox circles.

Communal interests focused primarily on local matters as Jewish suburbia built its institutions, while in older urban areas they had to struggle to survive or relocate.

Nearly every city, except New York and Chicago, conducted a combined campaign for overseas and domestic needs and had some form of central Jewish community organization.

The Jewish community councils, founded during the 1930s, generally merged with the older federations of Jewish philanthropies and were governed by an executive board and a none too potent community assembly of representatives from organizations. In some cities, however, contributors to the combined campaign above a minimal level (usually $10) were enfranchised to vote for a fixed proportion of the delegates to these assemblies. These central Jewish communal bodies promoted equal rights through their community relations committees which coordinated the local efforts of the leading Jewish defense organizations (*American Jewish Committee, *American Jewish Congress, *Jewish Labor Committee, *Jewish War Veterans). They also sponsored the local bureaus of Jewish education, settled intra-communal disputes, in some communities supervised kashrut [[Jewish nutrition rules]], and generally functioned as the recognized Jewish spokesmen in the general community. The social service agencies affiliated with the antecedent federations enjoyed far-reaching autonomy. The most important activity by far was the annual campaigns, whose proceeds were allocated, after negotiations, by carefully devised formulas.

At the national level, ideological groupings and specialization of activities evolved, but no stable central body developed. The defense organizations, mentioned above, coordinated their activities in the "National Community Relations Advisory Council. The *American Zionist Council did likewise for [[racist]] Zionist bodies, especially on political issues, and the *Synagogue Council, with little power, obtained occasional unity among the denominational federations of synagogues. The military functions of the *National Jewish Welfare Board were largely replaced by its peacetime activity of providing coordination and (col. 1640)

program assistance to approximately 300 Jewish community centers, and their 645,000 members, affiliated with it by 1960. The *Council of Jewish Federations and Welfare Funds guided and counseled its constituents by means of nationwide meetings, through intensive studies of Jewish philanthropic policy, of the role of government in education and social service, and through the activities of various beneficiaries.

In 1954 the *Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations (the "Presidents' Club") was established, with 17 members, to consult informally in matters concerning [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel and overseas Jewish problems. By virtue of its age, size, prestige, and non-partisan Jewish character, *B'nai B'rith tended to play a focal role in such central efforts.

[Schooling and school questions]

The relation between church and state, especially in the field of education, continued to be a touchy issue. The Jewish community maintained its historic opposition to religious observances in governmental functions and particularly in the schools. This stand was put to the test, especially over Catholic demands for government aid to their parochial school system. A series of Supreme Court decisions which permitted private schools to receive school buses, lunches, and textbooks from the government was generally regretted, while decisions which barred school prayers and any active role for schools in sponsoring outside sectarian religious instruction were widely applauded by Jews. The passage of the Education Act of 1964 and subsequent legislation, providing limited federal aid for private schools, tended to quiet the issue.

U.S. Jews also opposed school programs which aimed to inculcate "moral and spiritual values" in children. Local disputes frequently erupted, typically in predominantly Christian suburbs to which a substantial number of Jews had moved, due to Jewish opposition to Christmas observances in the public schools; combined Christmas-Hanukkah (Ḥanukkah) observances were a syncretistic "compromise".

Thus, the U.S. Jewish community continued its historic affinity for the public schools provided they were religiously neutral. Among Jewish organizations the [[racist Zionist]] American Jewish Congress took the most rigorous separationist position, while the American Jewish Committee leaned toward a more pragmatic acceptance of the prevailing public policy. Several theologians, including Mordecai M. Kaplan, Will Herberg, and Seymour Siegel, wished to modify the traditional Jewish separationism because of their conviction that the secular public school tended to inculcate secularism as a quasi-religion. Orthodox Jewry, which had few children in the public schools, also opposed rigorous church-state separation in education, partly in hopes of securing public funds for their hard-pressed day schools. (col. 1641) [[...]]

The American Jewish community has been most concerned with problems of church-state relationships in the post-World War II ear. Occasionally, as in the strong public reaction to the Supreme Court's decision in the Regents prayer case of 1962 in which public school prayers were declared unconstitutional, anti-Semitic overtones have been apparent. (col. 1656) [[...]]

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL PLACE IN AMERICAN LIFE.

[Since 1945: Jewish writing in English]

By the end of the 1940s the Jews as an overwhelmingly native group, extensively college educated and heavily concentrated in the mercantile and professional classes with long-standing cultural interests, began to assume a remarkable degree of prominence in U.S. cultural life. While their previously notable position as physicians, scientists, lawyers, psychoanalysts, and musicians continued, Jews now began to excel in fields once closed or inaccessible to them. Linguistic strangeness and the thematic content of U.S. literature had tended to make Jewish writers in English very few. But beginning in the 1950s a considerable number attained importance and true distinction: the novelists Saul *Bellow, Bernard *Malamud, and Norman *Mailer; playwrights like Arthur *Miller; poets such as Delmore *Schwartz, Allen *Ginsberg, and Karl *Shapiro;and the critics Lionel *Trilling, Leslie *Fiedler, Alfred *Kazin, and Irving *Howe. Moreover, Jewish subjects surged into the forefront of literary interest. Novels and short stories of (col. 1641)

extremely varied quality, on themes including the European Holocaust, [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel, and middle-class U.S. Jewish life, sold in the millions to gentiles as well as Jews. Plays on Jewish themes attracted vast audiences and were produced on nationwide television. Many of the above writers contributed to this movement, as did other successful novelists like Philip *Roth, Mayer *Levin, Leon *Uris, Irving Wallace, and the ex-Communist Howard *Fast. "Jewish" became a literary genre even surpassing the "Southern" or the "Middle Western". Occasional voices, questioning its naturalization into U.S. literature and even alleged domination by a New York Jewish circle, focused in such journals as *Commentary, the Partisan Review, and the New York Review of Books.

While this was largely literary politics or legitimate literary judgment, there was no doubt that Jews were the principal marketers of cultural products in the U.S., whether as impresarios of music, theatrical producers, editors, book publishers, or film and television producers.

[Since 1945: Jews in masses in university faculties]

A second major trend was that of Jews into the arts and sciences on university faculties. During the 1930s and earlier only a few hundred Jews held academic positions, mainly in the municipal colleges of New York City, but at the close of the 1960s an estimated 30,000 Jews composed about one-tenth of all college faculty members. They were distributed in all fields, although physics, sociology, and psychology particularly had a high proportion of Jews. No field of study, however, lacked notable Jewish contributors. Jewish professors could be found in almost all colleges, but especially in public institutions and in the "Ivy League".

By and large, Jewish contributors to U.S. cultural life, at least until the middle 1960s, were not rebels or path breakers, but excelled and advanced in the established forms. Their general orientation continued to be the liberal left, with echoes of earlier radicalism. To the Jewish community its "Jewish intellectuals" were somehow a source of concern: could they be made to demonstrate positive interest in established U.S. Judaism, and why did most of them shy away? A symposium on "Jewishness and the Younger Intellectuals", published in Commentary in May 1961, strongly suggested that under the cultural consensus and religiosity of the 1950s lay the alienated restlessness of many of the highly acculturated, talented young.

RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL LIFE.

[Jewry as a recognized "third U.S. religion"]

U.S. Jewish religious life considerably broadened after 1945 as Judaism was all but officially recognized as the "third U.S. religion".

[[The natives of the "USA" - the Indians - were not recognized, and all religions of the Black people in the criminal racist "USA" were not recognized, either]].

Public commission habitually included a Jewish member alongside Protestants and Catholics, and official ceremonies, including presidential inaugurations, arranged for Jewish as well as Christian clerical participation. The 1950s was a period of unprecedented interest in Jewish religious life and thought, as part of the "revival of religion" in U.S. culture during those years, and the writings of such figures as Martin *Buber and Abraham J. *Heschel received wide attention. Numerous interfaith institutes and assemblies were held. Indirectly the climate was created for the Jewish role in the Catholic ecumenical movement of the 1960s.

[Change of character of communities - numbers of communities and rabbis]

While it was customary to divide U.S. Judaism into Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox denominations, each with central institutions and recognized leaders, the reality resembled more a spectrum in which the membership beliefs, and practices, and even the rabbinate of one group shaded into the next. The number of denominationally identified congregations grew rapidly. In 1954 there were 462 Reform congregations, 102 more than in 1948; of the 473 Conservative there were 156 more than in 1948. (Many had been Orthodox and evolved into Conservatism). There were 720 affiliated Orthodox congregations, but many were inactive leftovers from immigrant days. The increase (col. 1642)

continued, so that in 1958 the congregations numbered 550 Reform, 600 Conservative, and again 720 Orthodox. The Synagogue Council estimated in 1957, however, 4,240 congregations in the U.S. This great disparity could be partially explained by the large number of minuscule, unaffiliated, and inactive bodies in the latter figure. The organized U.S. rabbinate in 1955 counted 1,127 men in the two large Orthodox professional bodies, 677 Reform, and 598 Conservative. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (B.L.S.) reached similar conclusions when it found in 1960, 2,517 congregational rabbis, 944 in "specialized Jewish community service", and 148 at temporary work or unemployed. To these 3,609 rabbis the B.L.S. added some 650 retired or out of the profession, and there were probably others privately ordained not functioning as rabbis.

A 1950 estimate placed total synagogue membership at a maximum of 450,000 families, besides about 250,000 persons who had seats in the synagogue on the High Holy Days. Perhaps 1,485,000 Jews were thus synagogally affiliated, and this figure apparently increased during the 1950s. Thus around 1958 there were over 450,000 families in Conservative and Reform congregations; the Orthodox could not be properly determined, but a 1965 study suggested 300,000 committed Orthodox individuals. Altogether, the largest institutions and membership growth was found among the Conservatives, who counted 833 congregations affiliated with the United Synagogue in 1970 as compared with some 700 in the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in that year.

[Synagogues and Jewish institutions in competition - percentage numbers - attendance questions]

A wave of synagogue construction permitted this increase of affiliation, as did the burgeoning of new suburban districts. Between 1945 and 1952 an estimated $50 to $60,000,000 was spent on synagogue building, and the ten-year period which followed may have seen twice that amount expended. Many synagogues, especially in the suburbs, accommodated not only worship and study but also quite elaborate social functions and even sports and social recreation. The tendency of synagogues to act as Jewish community centers sometimes brought them into rivalry with non-synagogal Jewish centers and Young Men's (and Women's) Hebrew Associations, which were professionally equipped for such work. The latter were engaged in reorienting their outlook and activities toward a more explicit Jewish program, as recommended in the influential JWB Survey directed by Oscar I. *Janowsky (1948).

The synagogue-Jewish center rivalry had some ideological basis: synagogal claims to primacy as the embodiment of Jewish religion and tradition, versus the centers' emphasis on their broadly Jewish character accommodating nonreligious as well as religious members.

Notwithstanding great material growth Jewish religious life hardly became more intensive. A careful poll taken in 1945 showed that 18% of the Jews attended public worship at least once monthly, to 65% of Protestants and 83% of Catholics. A 1958 poll of weekly attendance again showed 18% of Jews thus an apparent increase to 74% of Catholics and 40% of Protestants. Although U.S. Jews in questionnaires tended to describe themselves as "conservative" in religion, this probably indicated a general liking for religious tradition rather than actual Conservative synagogue affiliation.

There was widespread well-documented interest in Judaism on college campuses, and numerous instances occurred of young people adopting traditional religious life and beliefs. Altogether, however, only small minorities, estimated between 10% and 20%, observed the Sabbath scrupulously, maintained the dietary laws in full, and observed daily prayer. The three recognized religious groupings were found in every Jewish community of any size, but some were strong in particular cities. Thus, the (col. 1643)

centers of Orthodoxy were in Boston, Baltimore, and above all New York City. Philadelphia and Detroit were strongly Conservative, while Cleveland, San Francisco, and Milwaukee were largely Reform.

[The Jewish communities and their inner affairs: Jewish law for deserted Jewish wives - Orthodox non-Zionists and Orthodox anti-Zionists]

The denomination had their struggles over internal issues. The Reform majority, now pro-Zionist, moved toward increased ritual and traditionalism, over the opposition of a vigorous "classical Reform" minority, and congregations leaned in either direction. The majority of Reform rabbis attempted to utilize the classic sources of Jewish law in religious problems. Among the Conservatives differences tended to be muffled in loyalty to the central institution, the Jewish Theological Seminary and its profoundly traditionalist faculty. The main issue was Jewish law and the extent to which it could be modified within its own categories, and by whom. In an attempt to demonstrate the reality of the Conservative conception of halakhah [[Jewish law]] by solving the classic problem of freeing the deserted wife (agunah) from her marital bond, the Rabbinical Assembly promulgated a supplement in 1954 to the marriage certificate (tosefet ketubbah) and established a tribunal to deal with such cases.

Vigorously opposed by the Orthodox and by some Conservative dissenters, this method had rather mixed success in practice. Yet while the Conservative rabbis and scholars debated this and other halakhic [[Jewish law]] problems of change, the lay membership proceeded in its own unhalakhic way of life. Orthodoxy meanwhile shed its status as the Judaism of immigrants after the number of acculturated, middle-class congregations with modernist, U.S.-trained rabbinic leadership sharply increased. There was also a large accretion to Orthodoxy from post-1945 immigration, among whom Hasidim (Ḥasidim) and yeshivah [[religious Torah school]] leaders were prominent. Tensions arose between these two segments for the latter tended to be non-Zionist or anti-Zionist and considered that the secular world and non-Orthodox forms of Judaism had improperly influenced U.S. Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy became intellectually active as religious and philosophic writing, besides traditional rabbinic scholarship were produced. U.S. reprintings of the Talmud and nearly the entire corpus of rabbinic classics found a market mainly in Orthodox circles.

CULTURE AND EDUCATION.

[Jewish writing with linguistic assimilation - Yiddish publications reduced - Anglo-Jewish press, TV, and publications]

After 1950 Hebrew literary creativity in the U.S. nearly vanished as [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel increasingly monopolized talent and provided a mass audience for writers. Yiddish letters also continued their decline, largely on account of linguistic assimilation Significant Yiddish writers continued to publish, however, including Chaim *Grade and Isaac *Bashevis Singer, who in English translation became a U.S. literary celebrity during the 1960s. Yiddish was no longer the language of the Jewish masses: during the 1960s two daily newspapers were still published in New York City, besides the monthly *Zukunft [[Yidd.: Future]], *YIVO publications, and various organizational periodicals.

On the other hand, Jewish cultural activity in English surged. Its media included the weekly Anglo-Jewish press whose news came from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, in some sense synagogue sermons, the lecture platform of variable quality in Jewish institutions, and Jewish monthlies and quarterlies - some of which were of the highest standard. It was no longer unusual to read of Jewish affairs in the general press; and television and general magazines also frequently presented Jewish material from which unpleasant stereotypes had long been eliminated.

University presses and commercial publishers issued serious works on Jewish subjects, in addition to the best-selling novels and potboilers mentioned above.

[Jewish schooling at universities]

Jewish scholarship, while still concentrated in seminaries and yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]], slowly began to find a place in universities with the establishment of academic chairs in Jewish studies. To the generation of (col. 1644)

mature, European-trained scholars was added a new one educated in the U.S. and frequently in [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel. Learned studies of outstanding merit in [[criminal racist]] Bible, [[racist]] Talmud, medieval and modern Jewish languages and literature, philosophy and theology, history, and folklore were produced by the elder scholars and their younger colleagues.

[Schooling of the baby boomers since 1945: Sunday schools - Orthodox day schools - Yiddish education reduced - funds for Jewish schooling - shortage of teachers]

The low Jewish education level of U.S. Jewry places such works of learning beyond its comprehension, notwithstanding a new, respectful attitude toward Jewish scholarship. Jewish education "boomed" as school enrollment increased, owing particularly to the post-1945 "baby boom", from some 268,000 in 1950 to 589,000 in 1962. An estimated 80% of U.S. Jewish children received Jewish education at some time during their school years. Over half went to Sunday schools, which were generally attached to Reform congregations, and perhaps one-third to weekday congregational schools, usually branches of Conservative synagogues. A striking and somewhat controversial increase was that of day schools, most of them under Orthodox auspices, which enrolled approximately 80,000 children in 1970;

the lesser expansion of yeshivah [[religious Torah school]] high schools and of yeshivot for full-time talmudic study was also conspicuous. As these schools grew the communally supported talmud torahs [[Talmud Torah schools]] of earlier decades sharply declined owing to changing religious trends within the Jewish community and the change of urban neighborhoods;

secular Yiddish education barely survived. Local Jewish welfare funds began to appropriate more for Jewish education, mainly toward central bureaus and specialized services. Notwithstanding financial improvement and the desire of most parents to send their child to some Jewish school, Jewish education remained brief and superficial for most pupils, and was severely handicapped by a seemingly insoluble shortage of qualified teachers.

THE LATE 1960s.

[Vatican Council with rectification of the passive attitude of Pope Pius XII to the Holocaust - Catholic-Jewish conversations with only little results in 1965]

Toward the end of the 1960s the U.S. Jewish position seemed stable. Population held to predictable rates; immigration was minimal and readily absorbed; demographic and occupational trends continued as they had from approximately 1950; [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel attracted warm political and financial support and tourism; and the institutions of the Jewish community were generally well financed and seemed capable of dealing with most of the problems coming upon their agendas. Late in the 1960s, however, quite unanticipated matters and issues arose which stirred unusual interest and anxiety.

The accession of Pope John XXIII in 1958 and the Vatican II Ecumenical Council, which he convened, inaugurated sweeping changes in the Roman Catholic Church. These included a major attempt to rectify the ancient anti-Jewish record of the Church and to meet belated worldwide criticism of the passive or aloof attitude of Pope Pius XII during the European Holocaust. The movement within the Church to "exonerate" the Jews from "deicide" and to formally recognize the theological legitimacy of Judaism was highly active in the United States, and stirred considerable Jewish participation and enthusiasm. A period of Catholic-Jewish theological conversation and "dialogue" commenced, in which Cardinal Bea and U.S. prelates were leaders; the most prominent Jewish spokesman was Abraham J. Heschel. The final document issued by Vatican II in 1965 disappointed high hopes. While Catholic silence (as well as that of Protestants) during the Arab preparations to annihilate [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel in May 1967 was very disillusioning, Catholic-Jewish dialogue continued, but in a subdued key.

[Jewish students demonstrating for equal rights for the Blacks - relations between Jews and Blacks]

The acquisition of equal rights by U.S. Negroes had long been a goal of legal and political action, as well as philanthropic endeavour, by Jews. Not only did such Jewish organizations as the *American Jewish Committee and the (col. 1645)

*American Jewish Congress possess long records as supporters of legislation and litigants in court in order to secure Negro rights, but individual Jews since the days of Louis *Marshall and Julius *Rosenwald and the *Spingarns had long provided a large proportion of activists and funds in these struggles. During the "civil rights summers" of the mid-1960s young Jews constituted, by some reports, as high as 50% of all the white student youth who went south to assist Negroes. The passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965, and the legal and judicial prohibition of racial segregation in all forms, were viewed by Jews with deep satisfaction. (col. 1646) [[...]]

Jewish participation in the Negro civil rights movement of the 1950s and early 1960s brought charges from Southern extremists of attempts to "mongrelize" [[bastardize]] and communize America. In the late 1960s the shift of the Negro movement to greater militancy, the growth of black nationalism, and the emphasis on "black power" generated considerable friction in Negro-Jewish relations. Although surveys indicated that anti-Semitism among the mass of American Negroes is no greater, and perhaps less, than that existing among white Americans, and although moderate Negro leaders condemned anti-Semitism, the possibility of continued group conflict existed and seriously disturbed American Jewry in the late 1960s. (col. 1656) [[...]]

[[Addition: Struggle for rights and for peace in the criminal racist "USA" in the 1960s

In May 1963 the white racist police attacked a demonstration: During Mercury "Faith 7" in Birmingham (Alabama) the white police attacks black demonstrators with dogs. The children demonstrated for the lift of the apartheid in the "USA". Children are arrested. Ku Klux Klan burns down a hotel where foreign demonstrators stay over night. President Kennedy sends troops, then makes a trip through the South and praises the civil rights movement of Martin Luther King. The black Medgar Evers is murdered by a sniper in June 1963. On 28 August 1963 is the big final demonstration of the "March to Washington" with the speech of Martin Luther King "I have a dream". President Kennedy lets happen the demonstration which is too much for the white racists in the criminal "USA". So President Kennedy is murdered on 22 November 1963. On February 1965 the black civil right activist Malcolm X is murdered. Since 2 March 1965 the white racist policy of the criminal racist "USA" is going on against Vietnam with the operation "Rolling Thunder". On 3 April 1968 Martin Luther King is murdered, and on 5 June 1968 Robert Kennedy is murdered. In many towns of the criminal racist "USA" the white racist police is making war against black demonstrations and the blacks begin to fight. The fight combines with the Vietnam War demonstrations and peace camps which are fought by the white racist police. Peace demonstrators are even killed by the criminal white racist police of the criminal racist "USA", e.g., 4 students in Kent, the "Kent 4", on 4 May 1970. A considerable part of this racist war system of the "USA" is financed by Jewish bankers, and their children are demonstrating against the system. Finally the Blacks got their civil rights and were allowed to use a "white" toilet and to purchase land. But add to this the natives of the "USA" are never mentioned. They are sterilized, put into open air ghettos called "reservation", their spiritual culture is fought up to their destruction etc. Instead CIA is organizing a moon fake lasting for years with photos from moon studios with implanted flags without shadows and with cars without tracks...]]

[Further contacts between Jews and Blacks in the northern "USA" - Black competition against Jews]

After these victories, the long-established Negro-Jewish alliance was gravely strained and broken at many points, largely owing to the inner dynamics of Negro life (see *Negro-Jewish Relations). However, the presence within Negro areas of numerous Jewish merchants and slum landlords - many of whom were "holdovers" from earlier years when such districts were heavily Jewish - was also a source of friction. The whites with whom the masses of southern Negro migrants to northern cities came in contact were also disproportionately Jewish, including social case workers, lesser professionals, and, in New York City, public school teachers.

The wave of riots which swept northern Negro districts between 1964 and 1968 compelled the departure of most of their white businessmen, including Jews, and violently shook the delicate balance of urban peace. Militant movements of black separatism and nationalism denounced whites and repudiated their assistance in terms which were sometimes anti-Semitic. Proposals for social policy from some Negro and "establishment" white sources stirred deep Jewish fears that the economic and social gains of Negroes were to be at Jewish expense, with Jewish opportunities in higher education and broad areas of professional employment reduced to make room for Negroes.

[Teacher's strike in New York in 1968 - anti-Semitism and Jewish Defense League]

Other U.S. ethnic groups had similar fears. The strike by the New York City teachers in 1968, most of them Jews, arose from the intention of "school decentralization" to ease them out or reduce their opportunities for advancement in order to advance Negroes (and Puerto Ricans, in that city's situation) in the school system. Serious eruptions of anti-Semitism accompanied the strike, and the Jewish community was disturbed at white intellectual and upper-class indifference to them.

Deep cleavages appeared within the U.S. Jewish community as feelings emerged, especially among urban-working and lower-middle-class Jews, that the established Jewish organizations with their prosperous, suburban supporters were unconcerned with their plight and heedless of rising anti-Semitism.

The rapid (col. 1646)

growth of the Jewish Defense League (see *Self-Defense) in New York and other cities, with its tactics of physical defense, public demonstrations, and retaliation, expressed this fear.

[Contributions for racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl Israel after Six-Day War - "contributions" and exodus of 17,000 Jews - demonstrations against anti-Semitism in Soviet Union]

The crisis of May 1967 brought U.S. Jewish concern for [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel to a peak. Some volunteers were able to leave for [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel before June 5, 1967, but the tension and triumphant resolution in the Six-Day War found its main outlet in unparalleled contributions - $ 232,000,000 to the United Jewish Appeal and $75,000,000 in Israel bonds. Hardly had the euphoria of victory dissipated when the *New Left in shaky combination with Black militant elements vigorously espoused the Arab cause. Like Soviet Russia and Poland, they used "Zionist" as a synonym for Jew in attempting to obscure the anti-Semitic character of their propaganda. Together with numerous Arab students on U.S. campuses, they propagandized vigorously for their cause.

The [[racist]] Zionist movement, bland and quiescent for almost 20 years since U.S. Jews expressed their pro-Israel convictions outside its framework, somewhat revived after 1967. This was particularly noticeable at many colleges and universities, especially those swept by campus disturbances and the militant tone of leftist and black demands. Jewish students spontaneously founded [[racist]] Zionist organizations named in contemporary manner "liberation movements" and "radical". At a more sedate level, business investment in [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel as well as tourism, both overwhelmingly Jewish greatly increased despite the danger to Israel's security. Aliyah, long spoken of, became relatively numerous as approximately 17,000 U.S. Jews settled in [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel between July 1967 and the end of 1970.

Anti-Semitic discrimination and the near-suppression of Jewish life in the Soviet Union, together with the Soviet regime's refusal to permit Jewish emigration, furnished the main cause for agitation and protest by U.S. Jews at the end of the 1960s. The American Conference on Soviet Jewry, an "official" body, as well as the Academic Council on Soviet Jewry and the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, were the major organizers. The continued threat to the existence of [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] Israel, urban problems weighing heavily on an overwhelmingly urban community, and the surge of anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism, together with the well-publicized glorification of violence by some black militant demagogues and white followers, angered U.S. Jews and tended to stimulate a siege mentality. Assertions were common that Jewish communal life and institutions were useless and "irrelevant", and the supposed revolt of youth stirred concern. Nevertheless, U.S. Jews continued to support liberal political programs and candidates and played their customary prominent role in U.S. cultural and economic life.

[Jews in public life of the "USA"]

Less than a century after the U.S. was a distant, little populated outpost of the Jewish people, U.S. Jewry attained great numbers, prosperity, cultural eminence, and political prestige. Such growth and achievements had no precedent in the history of the Jews, just as those of the United States itself were unparalleled. In a new society without feudal, aristocratic, or churchly roots, most of the legal and social problems which preoccupied European Jewry during and long after its era of emancipation were pointless. Discussions of Jewish status sometimes had an apprehensive tone and anti-Semitism palpably existed, but U.S. Jews largely lacked the sense of the problematic about themselves within a continent-wide society composed of many religions and ethnic groups. U.S. Judaism was the creation of the Jewish common man who immigrated to the U.S. Humanitarianism, skill at organization, liking for innovation, and confidence in unlimited social and material improvement profoundly influenced Judaism. In U.S. life the Jewish role was far in excess of the small Jewish percentage of the (col. 1647)

population. Only the [[racist Zionist Free Mason CIA Herzl]] State of Israel played a greater role than did U.S. Jewry in the 20th-century transformation of the Jewish people.

[L.P.G.]> (col. 1648)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

========

Meldungen:

26.4.2012: Juden in den "USA" ab 1945 - Details

aus: Welt online: Migranten: Als Amerika für Juden das "Vierte Reich" wurde; 26.4.2012;

http://www.welt.de/kultur/history/article106228663/Als-Amerika-fuer-Juden-das-Vierte-Reich-wurde.html

<Jüdische Flüchtlinge gaben dem New Yorker Stadtteil nördlich der 135. Straße Namen wie "Viertes Reich" oder "Frankfurt". Wissenschaftler haben Stimmen der Migranten nach Amerika gesammelt.

Von Ludger J. Heid

Wohl aus Enttäuschung über die gescheiterte Märzrevolution des Jahres 1848 wandte sich der seinerzeit viel gelesene Schriftsteller Leopold Kompert mit einem programmatischen Appell: "Auf, nach Amerika!", an seine Glaubensbrüder, der im "Oesterreichischen Central-Organ für Glaubensfreiheit, Geschichte und Literatur der Juden" erschien. Kompert war der Pogrome und judenfeindlichen Übergriffe überdrüssig: Er wollte, dass die Juden nicht länger den "Nacken krumm" hielten.

Da er in Europa für Juden keine Möglichkeit mehr sah, Freiheit und bürgerliche Gleichstellung zu erlangen, riet er dazu, die jeweiligen Länder in Richtung Amerika zu verlassen. Kompert wollte seinen Aufruf als "Nothsignal", als eine "Lärmkanone" und als ein "Musikton in dieser wildgestörten Zeit" verstanden wissen und forderte die Juden auf, in Amerika Ackerbauern, Handelsleute oder Handwerker, Wechselagenten, Baumwollpflanzer - oder Mitglieder des Washingtoner Kongresses, oder gar "Vicepräsident des nordamerikanischen Freistaates" zu werden.

Warum Amerika? Der Kontinent war für Juden gleichsam die idealtypische Projektion für all das, was man in Europa nicht erreichen konnte, ein Eldorado, das "Promised Land", der jüdische Garten Eden. Dazu Joseph Roth: "Amerika ist die Ferne. Amerika heißt die Freiheit. In Amerika lebt immer ein Verwandter." Roths hymnisch besungenes Amerika ist nicht immer pfleglich mit seinen Einwanderern umgegangen. Seit den 1920er-Jahren praktizierte die USA verschärfte Einwanderungsbestimmungen, die nicht selten auf antisemitischen Vorurteilen beruhten.

"Das war bei uns besser"

Die Gegner Komperts hatten argumentiert, dass Auswanderung eine Aufgabe des Vaterlandes und ein Im-Stich-Lassen der Zurückbleibenden bedeute und mahnten auszuharren. In einem Offenen Brief beschwor David Mendel 1848 seine auswanderungswilligen Brüder: "Glaubt ihr wirklich, in Amerika das ersehnte Jerusalem zu finden? Wo noch Sklaverei als ein Recht geduldet wird, ist auch für Gleichberechtigung der Freien keine Garantie gegeben."

Dieses Argument ist nicht von der Hand zuweisen: Die meisten Einwanderer waren über die Jahrhunderte hinweg auf die bei ihrer Ankunft noch nicht aufgehobene Rassentrennung vorbereitet und rief bei ihnen die eigene Diskriminierung in Europa in Erinnerung.

Als Handicap erwiesen sich die Akzente, das "Emigranto", das viele Einwanderer mitbrachten: Ein Flüchtling sei ein importierter Exporteur, ein Mensch, der alles verloren habe außer seinem Akzent, lautete ein Witz. "Das war bei uns besser" – dieser Satz war in New Yorker Gegenden mit einem hohen Anteil an deutsch-jüdischen Einwanderern häufig zu hören, ganz so, als ob Adolf Hitler nie existiert habe. In Anspielung auf das "Dritte Reich" gaben die Flüchtlinge Washington Heights, dem Stadtteil nördlich der 135. Straße, den Namen "Viertes Reich", andere sprachen von "Frankfurt on the Hudson".

Kalaidoskop jüdischer Migrationsgeschichte

Ulla Kribernegg und Gerald Lamprecht haben diese und andere jüdischen Stimmen zu Amerika zusammengestellt. In ihrer kenntnisreichen Einführung heben die Herausgeber die Verschiebung der intellektuellen Zentren jüdischer Kultur hervor: Waren bis in die ersten Jahrzehnte des 20. Jahrhunderts Zentraleuropa und Deutschland mit der "Wissenschaft des Judentums" die Mittelpunkte jüdischen Lebens, so sind es nach 1945 die USA und Israel.

Freilich: Die These allein macht den Sammelband noch nicht herausragend. Bemerkenswert ist, dass dem Leser nun ein facettenreiches Kaleidoskop jüdischer Migrationsgeschichte vorliegt, eine Tour d'horizon durch zwei Jahrhunderte.

Ulla Kriebernegg, Gerald Lamprecht, Roberta Maierhofer, Andrea Strutz (Hrsg.): "Nach Amerika nämlich! Jüdische Migrationen in die Amerikas im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert". (Wallstein, Göttingen. 359 S., 24,90 Euro. ISBN 978-3835308862)>