|

|

|

Jews in Iraq 05: Jewish flight and exodus from Iraq 1948-1952 - Jewish culture in Iraq

| Share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

<From 1948

[since 14 May 1948-Dec 1949: Martial law - communism and the word "Zionism" are chargeable - the fight against the Jewish underground movement - death penalties]

From 1948 the departure of Jews from Iraq was forbidden until future notice. On May 14, 1948, when the State of Israel was proclaimed, martial law was declared in Iraq, and military courts set up. Hundreds of Jews were arrested and their houses searched.

[[Supplement: Zionist Herzl Free Mason Israel is a "US" satellite

Zionist Israel was not only a Herzl state without borders, but Zionist Israel also had become a satellite of the "USA". So the Arabs knew what meant the threat in the Herzl book that Arabs can be driven away like the natives in the "USA". The danger was absolutely real. That's why the Jews were prosecuted in all Arab countries from now on, and the escalation has been going on and on and has never stopped until now. Criminal "USA" serves to Zionism and vice versa with the aim of Great Israel. And the western TV stations never told this and never tell this until today (2007)]].

In July 1948 the criminal code (article 51(a)), which prescribed imprisonment for seven years or even death for those found guilty of communism, was amended to include the word "Zionism". Since military courts judged on the evidence of two (col. 1452)

witnesses, it was not difficult for anyone wishing to take revenge on a Jew, to find a second witness to testify with him as to a particular Jew being a "Zionist". There was no appeal against these sentences and military courts imposed on the Jewish detainees heavy fines (up to £ 10,000 = $ 40,000) and / or terms of imprisonment. Others were banished to other towns without benefit of trial.

The aim of the authorities was to fill the government treasury with the money of the Jews and break up the Jewish underground movement. Only one Jews, Shafiq Adas, was sentenced to death and hanged in Basra, on the charge of selling arms to Israel. Sasson Dallal and Yehudah Sadiq, leaders of the clandestine communist party, were sentenced to death on charges of communism, and were hanged in 1949.

[[The general persecution can be seen as a policy in the line of the "Soviet Union" which was the ally of the Iraq. The general persecution is one of the main faults of the Iraqi policy because it can be admitted the the majority of the Iraqi Jews was anti-Zionist. Buth the general persecution drove them into the hands of Herzl Israel propagandists]].

These persecutions increased the Jews' desire to leave Iraq. However, until martial law ended in December 1949, the Muslim masses did not turn against the Jews, and there were no pogroms.

MASS EXODUS.

[March 1950-August 1951: Operation "Ezra and Nehemiah" - most of the Jews leave Iraq for Zionist Israel]

The wave of arrest decreased in September 1948, was renewed in September 1949, and ended only with the end of martial law (December 1949). After this, tens of thousands of Jews fled illegally to Iran. Some continued to Israel immediately, others later.

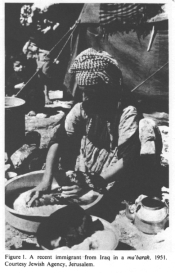

On March 9, 1950, the authorities changed their attitude and permitted Jews to leave the country if they would relinquish Iraqi nationality. Thus, in May 1950 the legal mass exodus to Israel began. It ended in August 1951, after the large majority of Jews (about 110,000) had left for Israel. The "Ezra and Nehemiah Operation" was organized by the Jewish Agency with the help of the underground organization, which registered the emigrants. Together with the refugees who fled through Iran, approximately 123,500 Iraqi-born Jews settled in Israel between 1948 and 1951.

Legal emigrants were permitted to take with them only 50 dinars (about $ 140) per adult and 20 dinars per child. They had to submit to customs inspection which was painstaking and rough in order to prevent them smuggling out capital.

On March 10, 1951, the Iraqi government passed a Law for the Control and Management of the Assets of Denaturalized Iraqi Jews, which froze the assets of Jews who had renounced their nationality. An additional order issued in the same month also froze the assets of Jews who left Iraq after the beginning of 1948 and had not returned by May 1951. Thus, assets valued at about $ 200,000,000 were transferred to the administration of an official, who was permitted to sell part or all of them.

[Returnee law - trials against Jewish nationalists]

During martial law all Iraqi citizens abroad were requested to return within a limited period if they wished to prevent confiscation of their property. A few Iraqi nationals were tried in absentia and sentenced to pay large fines, to imprisonment, and even to death.

SELF-DEFENSE AGAINST PERSECUTION.

[1950-1951: Two bombs in Baghdad near Jewish facilities - clandestine Zionist organization He-Halutz]

Between April 1950 and January 1951 bombs were placed near two Jewish firms in Baghdad, and near the United States Information Service building, and in January 1951 a bomb was planted near a Baghdad synagogue, in which many Jews had gathered to register for emigration to Israel. Three Jews were killed and others wounded. The Iraqi authorities contended that the bombs were planted by Jews, to humiliate Iraq in the eyes of the world. In June 1951 several dozen Jews were arrested, a few of whom were accused of planting bombs. In December 1951 two of them, a lawyer, Joseph Basri, and a shoemaker, Abraham Salih, were condemned to death. They were hanged publicly in January 1951.

These two young men had been active in the clandestine Zionist organization, He-Halutz, established in 1942. They organized in small cells, which gathered secretly to study Hebrew and follow developments in Palestine.

[Haganah war organization in Iraq]

About 600 members of the Haganah were instructed in the use of weapons in (col. 1453)

Baghdad, Basra, and Kirkuk. In 1949/50 the Haganah helped to organize the illegal exodus to Israel, and in 1951 it was decided to hide the arms. In this last activity Basri and Salih were caught, together with dozens of other members of the Haganah.> (col. 1454)

Culture of the Jews in Iraq

OCCUPATION.

There are no Iraqi government statistics on the occupations of Jews. Some idea may be gathered from the 30,011 Iraqi-born breadwinners who arrived in Israel in 1950/51. Of these 32% were artisans (11.3% tailors or in the textile industry), 27.5% engaged in trade, 15.8% officials and administrators, 6% members of the liberal professions (physicians, lawyers, teachers), 3.3% farmers, 2.4% in transport, 1.5% builders, 4.3% in personal services, and the rest, 7.2%, were unskilled workers.

Since there were no farmers, porters, or labourers among those few thousand Jews who remained in Iraq or left after 1951, most of these being merchants and professional men, it can be assumed that on the eve of the mass emigration about 30% of Iraqi Jews were engaged in trade, 25% were officials or professional men, 3% were farmers (almost all of them in Kurdistan), and the rest artisans, building workers, and workers in services.

Many of Iraq's bank clerks and railway and postal officials were Jews. At the end of World War I the percentage of officials and members of the liberal professions was much lower, while the percentage of artisans was higher, and the change is to be attributed to the spread of education between the two world wars.

EDUCATION OF IRAQI JEWRY.

The progress of education is indicated indirectly by the Israel census of 1961. Among Iraqi-born Jews aged 60 and over, there were 72.2% illiterates (48.7% of the men and 93.2% of the women), whereas among young people aged between 15 and 29, 30.5% were illiterate (17.3% of the men and 43.9% of the women). Most of the male illiterates were Jews from Kurdistan, where even on the eve of mass emigration there were young people who did not attend school and sometimes did not even go to heder [[Hebrew school]].

IN southern and central Iraq most of the younger generation received an education, and in 1950 over 20,000 Jewish youth studied in schools. During that year, approximately 110 young Jews graduated from Iraqi and foreign universities (as against five to ten university graduates per year during the 1920s).

In the Hebrew schools of Iraq in 1950 there was a total of 370 classes, 506 teachers, and 16,594 male and female pupils. A training center for the blind was also opened. In addition, about 30 students studied at yeshivot [[Jewish religious schools]] and several hundred Jews attended government schools, especially in the provincial towns. The level of education of the Jewish schools was high. The percentage of Jews who succeeded in matriculation examination was as high as 90% (while that of the Muslims was 40%). Many of these pupils went on to a university education in Iraq and abroad.

[since 1935: Zionist education is forbidden in Iraq]

Until 1925 a specifically Hebrew and Zionist education was given. Once Zionism was prohibited (1935), the teachers from Palestine were expelled. The study of Hebrew language and literature was forbidden and Jewish studies were restricted to Bible lessons. The rise of education caused assimilation and the abandonment of Judaism among the younger generation.

In 1950 many young Jews did not observe Jewish practices; some of them - those who did not attend Jewish schools - knew little about their religion, did not know how to pray, and could not read Hebrew. However, there were almost no conversions to Islam.

EMANCIPATION OF JEWISH WOMEN.

Jewish women in Iraq were by 1950 more emancipated than the preceding generation (not including the Kurdistan Jewish women). They received more education, and there were even a few women lawyers and physicians. Jewish women, especially in Baghdad, ceased wearing the enveloping robe and veil that all Iraqi women wore. The age at which Iraqi Jewesses married also rose. Only 15% of Iraqi Jewesses between the ages of 15 and 19 who arrived in Israel from 1948 to 1952 were married (as against 12% among European immigrants).

[Falling death rate and falling infant mortality]

However, there is no proof that the birthrate had fallen among Jews in Iraq, although it is certain that the death and infant mortality rates had dropped. As a result, the natural increase among Iraqi Jews in the mid-20th century was considerable. For every 1,000 women in the child-bearing age group (15-49) who arrived in Israel between 1948 and 1952, there were 576 children aged up to 4 years. The decline in the death rate caused a rise in life expectancy; thus, among Iraqi immigrants during this period, 7.2% were aged 60 and over, as against 5.3% of Yemenite and Adeni immigrants. [[...]]

[H.J.C.]> (col. 1454)

<Musical Traditions.

[Melodies for the psalms, synagogue chants a.o.]

In view of the antiquity of the community, one could assume that ancient elements have been preserved in their traditional music. A long period of cultural decline however, and contact with the powerful and flourishing music of the Muslim world, of which Iraq was for a long time an influential center, deeply marked their music and somehow altered their pre-Islamic heritage. Although it is difficult to trace a border line between the older and the more recent elements, it would appear that older elements have been preserved only in the biblical cantillations and some of the synagogal melodies.

The second volume of A.Z. Idelsohn's Thesaurus of Hebrew-Oriental Melodies (1923) contains the Babylonian traditions. Idelsohn classified the synagogal melodies according to 13 basic "modes", but these are fairly common to many of the Near Eastern communities. However, the Babylonians also had a number of melodic patterns peculiarly their own. One of these is the "lamentations mode", for which Idelsohn could find an analogy only in the chants of the Syrian Jacobites and the Copts (cf. Thesaurus II, no. 17). It has become possible to identify still another Babylonian "lamentations mode", which shows similar archaic features (see A. Herzog and A. Hajdu in: Yuval I. 1968, pp. 194-203). In this context it is surely significant that *Al-Harizi in his Tahkemoni (ch. 18) emphasized the mournful character of their songs, while denigrating the Babylonian poets.

From the early Middle Ages the Babylonian rabbinic authorities were known for their strict adherence to traditional liturgical chant. One of the oldest masters of post-talmudic synagogal chant was *Yehudai b. Nahman Gaon of Sura (eight century), whose tradition was supposed to go back to the talmudic period. A vivid description of responsorial and perhaps even choral singing in tenth-century Baghdad is given in *Nathan b. Isaac ha-Bavli's description of the installation of an exilarch. Benjamin of Tudela reports from his travels (c. 1160-80) that Eleazar b. Zemah, the head of one of the ten rabbinical academies of Baghdad, and his (col. 1458)

brothers "know how to sign the hymns according to the manner of the singers of the Temple". Another traveler of the same period, *Pethahiah of Regensburg, gives a most picturesque description of the simultaneous talmudic chanting of the 2,000 pupils of Samuel b. Ali's yeshivah at Baghdad. He also reports that the Jews there "know a certain number of traditional melodies for each psalm", and on intermediate days (hol ha-mo'ed) "the psalms are performed with instrumental accompaniment."

The instrumental skill went side by side with the creation of a rich repertoires of folk and para-liturgical song in Judeo-Arabic by Babylonian poets. A great number of talented instrumentalists and singers rose to prominent positions in the musical life of the surrounding culture. The best known of these, in the 19th and 20th centuries, were the kaman player Biddun, the singers Reuben Michael Rajwan and Salman Moshi, the santour player Salih Rahmun Fataw and his son, and the oud player Ezra Aharon. Aharon immigrated to Palestine shortly afterward, and became well-known through his broadcasts. Other distinguished musicians from Iraq (and Egypt) followed him.

Customs.

Bridegrooms were accompanied on the Sabbath from the synagogue to their house by gentile musicians, but later the rabbinical authorities forbade this practice. Women also took part in many musical activities.

Until 1950 there existed in Baghdad a famous group of four or five women singers and players called Daqaqat, who performed only at Jewish family rejoicings and festivities. There were also the woman wailers, both professional and private. Their most notable appearances were at the mourning ceremonies for young people not yet married: two groups of women chanted antiphonally, first wedding songs and then lamentations, beating their breasts and scratching their faces.

There are specific songs in Judeo-Arabic for many different occasions. The most prominent categories are the wedding songs, Holy Land praises, lullabies, and songs for the ziara or Shavout pilgrimages, mainly to the venerated tombs of the prophets Ezekiel and Ezra. Jews from many parts of the country were accustomed to spend several days there, during which time music and dance played a prominent role.

Many fold songs were written down and are to be found in manuscripts with musical indications, such as the maqama or the name of the song to the melody of which the poem has to be sung (see especially Ms. Sassoon 485). Sometimes the poets composed according to the rhythm, rhyme, and even used the first verse of a given song with slight changes. A number of the songs in Judeo-Arabic have an introduction in Hebrew in the form of a prayer or of a laudatory nature. This introduction is usually sung by the public as a refrain after each verse sung by a soloist. Almost all the folk songs are performed in this sort of responsorial style.

For the musical traditions of Iraqi Kurdistan, see *Kurdistan, musical tradition.

[AM.SH.]> (col. 1461)

Culture of the Kurdish Jews until 1951

[Peaceful life for Jews in Kurdistan - widespread illiteracy - early marriages - superstitions - no persecution]

<About 19,000 Kurdish Jews lived in Iraq in 1948, most of them scattered throughout dozens of villages in northern Iraq, and in the towns of Irbil, Sulaimaniya, and Zakhu. Some of them also lived in Mosul, Kirkuk, and Baghdad, where they came in search of work after World War I. As late as 1950 most Kurdish Jews were villagers, and a large proportion were farmers.

According to a survey of Kurdish immigrants to Israel between 1948 and 1951, it is estimated that 20% had been farmers. This community was thus more agricultural than any other Jewish community. The rest were peddlers and artisans (including porters and construction workers). Only a few were rich. Hardly any Kurdish Jews were members of the liberal professions, with the exception of a few doctors and lawyers.

As in local Muslim communities illiteracy was widespread, since most villages did not possess any educational institutions. In Iraq there was no perceptible improvement in the status of the Kurdish Jewess. Women, even the young ones, generally remained illiterate and married at an early age (between 13 and 15), according to their father's decision. However, polygamy was rare; among immigrants to Israel there were only a very few wealthy Kurdish Jews who had two wives. Kurdish Jews in Iraq were mostly pious, although they regarded superstitions, such as amulets and pilgrimages to graves of holy men, as part of the Jewish religion.

Their relations with the Kurdish Muslims were generally good, especially from 1948 onward. The central government did not persecute them during the period of martial law. The impressions of travelers that Kurdish Jews were in bondage to Muslim tribes are untrue. The Jews, like the smaller Muslim tribes, lived under the protection of a larger tribe which guarded them from robbery and murder.

When they all left for Israel in 1950-51, they did so freely and did not have to pay any money to their "protectors". In several places, particularly in the town of Irbil, the clandestine Zionist He-Halutz organization spread Hebrew and Zionist education and instructed some of its members in farming. No Jews remained in Kurdistan after 1951.

[H.J.C.]> (col. 1456)

[[The Zionist Free Mason organizations allured all Kurdish Jews into the trap of Herzl Israel]].

^