Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Poland

03: 1772-1914

Unsuccessful reform plans - emancipation since 1862 -

movements and parties with and without assimilation -

anti-Semitism with boycott in 1912

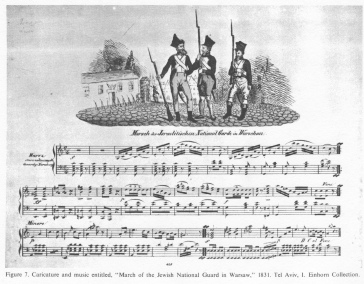

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland,

vol. 13, col. 733-734. Nineteenth-century

caricature of Jews in the Polish militia

[[Jews are in the army but cannot understand

Polish]]. The text reads: " 'You Jews

listen to my command: Attention, present

arms!' 'What did he say? What did he say?'

Herschel thereupon asked the corporal."

Tel Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland,

vol. 13, col. 733-734. Nineteenth-century

caricature of Jews in the Polish militia

[[Jews are in the army but cannot understand

Polish]]. The text reads: " 'You Jews

listen to my command: Attention, present

arms!' 'What did he say? What did he say?'

Herschel thereupon asked the corporal."

Tel Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne733-734-juden-in-armee-o-polnisch-19jh-20pr.jpg) |

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 733-734. Encyclopaedia

Judaica

(1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 733-734.

Nineteenth-century caricature of Jews in the

Polish militia [[Jews are in the army but cannot

understand Polish]].

The text reads: <"You Jews listen to my

command: Attention, present arms!" "What did he

say? What did he say?" Herschel thereupon asked

the corporal.>

Tel Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection |

from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 13

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

[The different parts of

ancient Poland and their authorities]

<AFTER PARTITION.

The geographic entity [[existence]] "Poland" in this part of

the article refers to that area of the Polish commonwealth

which, by 1795, had been divided between Austria and Prussia

and which subsequently constituted the basis of the grand

duchy of Warsaw, created in 1807. Following the Congress of

*Vienna in 1815 much of this area was annexed to the Russian

Empire as the semi-autonomous Kingdom of Poland, also known as

Congress Poland. The kingdom constituted the core [[center]]

of ethnic Poland, the center of Polish politics and culture,

and an economic area of great importance. It is to be

distinguished from Austrian Poland (Galicia), Prussian Poland

(Poznan, Silesia, and Pomerania), and the Russian northwestern

region also known as Lithuania-Belorussia.

[[Silesia and Pomerania were 100 % German since approx.

1400]].

[Polish plans to reform

Jewish life to be "useful" citizens - assimilation thesis

and steps: abolition of the assembly in 1822 - liquor tax -

new professions - enlightened rabbinical seminary -

emancipation since 1862]

During and after the partitions the special legal status

enjoyed by the Jews in Poland-Lithuania came under attack

while disabilities [[discriminations]] remained, efforts were

made to break down the Jews' separateness and transform them

into "useful" citizens. This new notion [[intention]], brought

to Poland from the west and championed by Polish progressives

with the support of the tiny number of progressive Jews,

advocates of the Haskalah, was clearly expressed during the

debates on the Jewish question at the Four-Year Sejm

(1788-92). The writings of H. Kollantaj and M. *Butrymowicz

demanded the reform of Jewish life, meaning an end to (col.

732)

special institutions and customs (from the kahal [[assembly]] to the

Jewish beard), sentiments to be expressed later on by S.

Staszic and A.J. *Czartoryski. The attack on "l'état dans

l'état" [["The State in the State"]], as Czartoryski put it in

1815, was accompanied by an attack against Jewish economic

practices in the village, which, it was claimed, oppressed and

corrupted the peasantry.

From Butrymowicz, writing in 1789, to the writings of Polish

liberals and Jewish assimilationists in the inter-war period,

there runs a common assumption [[idea]]: the Jews suffer

because they persist in their separateness - let them become

like Poles and both they and Poland will prosper. This

assumption was also shared by many anti-Semites of the

non-racist variety.

Some effort was made during the 19th century to implement this

belief. For example, the kahal

[[assembly]], symbol of Jewish self-government, was abolished

in 1822, and a special tax on Jewish liquor dealers forced

many to abandon their once lucrative profession. On the other

hand Jews were encouraged to become agriculturalists and were

granted, in 1826, a modern rabbinical seminary which was

supposed to produce enlightened spiritual leaders. Moreover,

in 1862 the Jews of Poland were "emancipated", meaning that

special Jewish taxes were abolished and, above all, that

restrictions on residence (Jewish ghettos and privilegium de non tolerandis

Judaeis) were removed.

[Anti-Semitism in Russian

Congress Poland since 1891 - expulsions from villages -

quotas - Jewish resistance with productivity and isolation]

Nonetheless, the legal anti-Semitism of Russia's last czars

was also introduced into Poland: in 1891 aspects of N.

*Ignatiev's *May Laws were extended to Congress Poland,

resulting in the expulsion of many Jews from the villages, and

in 1908 school quotas (*numerus clausus) were officially

implemented. In sum, during the 19th and early 20th centuries

the policy of the carrot and the stick [[sugar cake and

punishment]] was employed. By the end of the pre-World War I

era the stick had prevailed [[dominated]], making the legal

status of Polish Jewry nearly identical to that of Russian

Jewry. The efforts to assimilate Polish Jewry by legislation

aimed at making it more productive and less separatists had

virtually no impact on the Jewish masses.

[High Jewish birth rate and

Jews concentrating in towns]

The "Jewish question" in Poland and the legal efforts to deal

with it were to a certain extent the result of the Jews'

special demographic and economic structure. From the

demographic point of view two striking tendencies may be

observed. First, the natural increase of Polish Jews was

greater than that of non-Jews, at least during most of the

19th century, leading to an increasing proportion of Jews

within the population as a whole. In 1816 Jews constituted

8.7% of the population of the kingdom; in 1865, 13.5%. In

1897, despite the effects of large-scale Jewish emigration, 14

out of every 100 Polish citizens were Jews. This increase,

attributable in part to the low Jewish death rate, was

accompanied by the rapid urbanization of Polish Jewry. A few

examples may suffice to illustrate this important process.

Table 4 demonstrates the growth of Warsaw Jewry, where

restrictions on residence were not entirely lifted until 1862:

Table 4.

Growth of Warsaw Jewry

|

Year

|

Number

of

Jews

|

Percentage

|

1781

|

3,532xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

|

4.5%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1810

|

14,061xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

18.1%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1856

|

44,149xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

24.3%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1882

|

127,917xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

33.4%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1897

|

219,141xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

33.9%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

| from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971,

vol. 13, col. 735 |

A similar trend is found in Lodz, the kingdom's second city

(see Table 5): (col. 735)

Table 5.

Growth of Lodz Jewry

|

Year

|

Number

of

Jews

|

Percentage

|

1793

|

11xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

5.7%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1856

|

2,775xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

12.2%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1897

|

98,677xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

31.8%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1910

|

166,628xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

40.7%xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

| from: Poland; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971,

vol. 13, col. 736 |

This remarkable urbanization - the result of government

pressure, a crisis in the traditional Jewish village

professions, and the economic attractions of the growing

commercial and industrial centers - had the following impact

on the Jewish population:

in 1827, according to the research of A. Eisenbach, 80.4% of

the Jews lived in cities and the rest in villages, while in

1865 fully 91.5% of Polish Jewry lived in cities. In the same

year 83.6% of the non-Jewish population lived in the

countryside. As early as 1855 Jews constituted approximately

43% of the entire urban population of the kingdom, and in

those cities where there were no restrictions on Jewish

settlement the figure reached 57.2%. The Jews, traditionally

scattered, could claim with some justification that, by the

end of the century, the cities were their "territory".

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 728. Engraving of a Jew from Warsaw and his wife.

From L. Hollaenderski: "Les Israélites de

Pologne" [[Israelites in Poland]], Paris, 1846.

Jerusalem, Israel Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

728. Engraving of a Jew from Warsaw and his wife. From

L. Hollaenderski: "Les Israélites de Pologne"

[[Israelites in Poland]], Paris, 1846. Jerusalem, Israel

Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne728-jude-u-juedin-Warschau1846-36pr.jpg)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 728. Engraving of a

Jew from Warsaw and his wife.

From L. Hollaenderski: "Les Israélites de Pologne"

[[Israelites in Poland]], Paris, 1846.

Jerusalem, Israel Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem

[Professions: trade - banks -

financing for industrialization - credits]

This demographic tendency meant that the traditional Jewish

economic structure also underwent certain changes. Jews, of

course, had always predominated in trade; in 1815, for

example, 1,657 Polish Jews participated at the Leipzig fair

compared with 143 Polish gentiles. During the course of the

century, as the Jews became more and more dominant in the

cities, their role in urban commercial ventures became

more pronounced. Thus, in Warsaw, at the end of the century,

18 out of 26 major private banks were owned by Jews or Jewish

converts to Christianity. A wealthy Jewish merchant and

financial class emerged, led by such great capitalists as Ivan

*Bliokh and Leopold *Kronenberg, who played a role in the

urbanization and industrialization of Poland.

On the other hand, the vast majority of Jews engaged in

commerce very clearly belonged to the petty bourgeoisie of

shopkeepers (of whom, in Warsaw in 1862, nearly 90% were Jews)

and the like. In the same year, according to the calculations

of the economic historian I. *Schiper, more than two-thirds of

all Jewish merchants were without substantial capital.

[1862-1898: Christian trade

and Jewish crafts - some rich Jews and many in tiny shops -

Jewish professional class]

Two tendencies must be emphasized with regard to the Jewish

economic situation in the kingdom. First, it became apparent

by the end of the century that the Jews were gradually losing

ground to non-Jews in trade. Thus, for every 100 Jews in

Warsaw in 1862, 72 lived from commerce, while in 1897 the

figure had dropped to 62. For non-Jews on the other hand, the

percentage rose from 27.9 in 1862 to 37.9 in 1897. The rise of

a non-Jewish middle class, with the resulting increase in

competition between Jew and gentile, marks the beginning of a

process which, as we shall see, gained impetus during the

interwar years.

Second, there was a marked tendency toward the

"productivization" of Polish Jewry, that is, a rise of Jews

engaged in crafts and industry. The following figures, which

relate to the whole of Congress Poland, are most revealing: in

1857 44.7% of all Jews lived from commerce and 25.1% from

crafts and industry, while in 1897 42.6% were engaged in

commerce and 34.3% in crafts and industry. In this area, as in

trade, the typical Jew was far from wealthy.

For every wealthy Jew like Israel Poznański, the textile

tycoon from Lodz, there were thousands of Jewish artisans

(some 119,000, according to the survey of the *Jewish

Colonization Association (ICA) in 1898) who worked in tiny

shops with rarely more than one hired hand. It is noteworthy

that for various reasons - the problems of Sabbath work, the

anti-Semitism of (col. 736)

non-Jewish factory owners, fear of the Jewish workers'

revolutionary potential - a Jewish factory proletariat failed

to develop. Even in Lodz and Bialystok the typical Jewish

weaver worked in a small shop or at home, not in a large

factory.

One further development should be mentioned. By the end of the

century a numerically small but highly influential Jewish

professional class had made its appearance, particularly in

Warsaw. This class was to provide the various political and

cultural movements of the day, Jewish and non-Jewish, with

many recruits, as well as to provide new leadership for the

Jewish community. (col. 737)

[Integration is not always

possible: Jews in peasantry and in Polish legions in the

Polish army - Polish-Jewish periodical for assimilation -

lack of Polish language]

The Jews therefore, constituted an urban, middle class and

proletarian element within the great mass of the Polish

peasantry. There existed in Poland a long tradition of what

might be called a "Polish orientation" among Jews, dating back

to the Jewish legion which fought with T. *Kościuszko in 1794

and continuing up to the enthusiastic participation of a

number of Jews in J. *Pilsudski's legions. The Polish-Jewish

fraternization and cooperation during the Polish uprising of

1863 is perhaps the best example of this orientation, which

held that Polish independence would also lead to the

disappearance of anti-Semitism. The idea of Jewish-Polish

cultural assimilation took root among the Jews of the kingdom

far earlier than in Galicia, not to mention multi-national

Lithuania-Belorussia. *Izraelita,

the Polish-Jewish periodical advocating assimilation, began

publication in 1866, and a number of Jewish intellectuals like

Alexander *Kraushar hoped for the eventual merging of the Jews

into the Polish nation. Such men took comfort from the views

of a few Polish intellectuals, notably the poet Adam

*Mickiewicz, who hoped and worked for the same event. The

slogan "for our and your freedom" had considerable influence

within the Polish-Jewish intelligentsia by the century's end.

The Jewish masses, however, had nothing to do with such views,

knew nothing of Mickiewicz, knew little if any Polish, and

remained (as the assimilationists put it) enclosed within

their own special world. Here, too, as was the case regarding

the economic stratification of Polish Jewry, a thin stratum

separated itself from the mass. It was usually the offspring

[[son]] of the wealthy (Kraushar's father, for example, was a

banker) who championed the Polish orientation, while the

typical Jewish shopkeeper or artisan remained Yiddish-speaking

and Orthodox. O the Polish side, too, Mickiewicz was a voice

crying in the wilderness.

Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 733-734. Caricature

and music entitled,

"March of the Jewish National Guard in Warsaw", 1831. Tel

Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection

[Pogroms concentrated in the

Ukraine - anti-Semitism in Polish political parties - racist

Zionist declaration provoking more anti-Semitism - boycott

1912]

It is true that the great wave of *pogroms in the Russian

Empire was concentrated in the Ukraine and Bessarabia

(although Russian Poland was not wholly spared); nor was there

anything in Poland resembling the expulsion of the Jews from

Moscow in 1891. Indeed, Russian anti-Semitism led to the

influx of so-called "Litvaks" into the kingdom. But the rise

of Polish national fervor [[passion]], accompanied by the

development of a Polish middle class, naturally exacerbated

[[made bitter]] Polish-Jewish relations. The founding of the

National Democratic Party (*Endecja) in 1897 was symptomatic

of the growing anti-Semitism of the period.

[[Racist Zionism with the

claim for civic an national rights in the Helsingfors

declaration of 1906 lead into anti-Semitism in Poland]]:

<[[...]] Polish population, which initially favored the

idea of a movement likely to enlarge the scope of Jewish

emigration. This situation changed considerably, however,

when the [[racist]] Zionist movement proclaimed as a part of

its immediate aims the struggle for civic and national

rights for the Jewish population, as formulated in the *

Helsingfors

Program of 1906 [[Helsinki Program]]. The reaction of

the authorities was a marked reduction in tolerance toward

[[racist]] Zionist activites and anti-Semitism spread among

the Polish population, leading even to an economic boycott

of the Jews, which continued until the outbreak of World War

I.>

( from: Zionism; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 16,

col. 1130)

The economic and political roots of this anti-Semitism (not to

mention the traditional religious factor) were clearly

expressed in 1912, when the Jews' active support of a

Socialist candidate in elections to the *Duma resulted in an

announced boycott of Jewish businesses by the National

Democrats. On the eve of World War I relations between Poles

and Jews were strained to the utmost, a state of affairs which

led to a decline in the influence of the assimilationists and

a rise in that of Jewish national doctrines.

[[Positive examples of Poles and Jews are not mentioned]].

[No strong Jewish

enlightenment movement in Poland - assimilated Jewish

intelligentsia - Bund - racist Zionists against

assimilation]

In comparison with Russia, specifically Jewish political

movements had a late start in the kingdom. The Haskalah,

progenitor of modern Jewish political movements, was far less

influential in Poland than in Galicia or Russia. (col. 737)

Warsaw, unlike *Vilna, Lvov, and other great Jewish cities,

did not become a center of the Enlightenment; its Jewish

elite, like the elite in Germany, tended toward assimilation.

True, the city of *Zamosc was, for a time, a thriving Haskalah

center, but Zamosc was part of Galicia from 1772 to 1815 and

followed the Galician rather than the Polish pattern. Later

on, the pioneers of Jewish nationalism and Jewish Socialism

came from the northwest region (Belorussia-Lithuania) or the

Ukraine.

While in Lithuania the Jewish intelligentsia, though

Russianized, remained close to the masses, in Poland the

intelligentsia was thoroughly Polonized. Its members tended,

therefore, to enter Polish movements, such as the Polish

Socialist Party (*PPS). Thus the *Bund, although it succeeded

in spreading into Poland in the early 20th century, remained

very much a Lithuanian movement. It is striking that the

so-called "Litvaks" played a major role in spreading the ideas

of Jewish nationalism to Poland; it was they, for example, who

led the Warsaw Hovevei Zion (*Hibbat Zion (Ḥibbat Zion))

movement, the precursor of modern [[racist]] Zionism.

[[Anti-Zionists in Poland who saw that Zionism would be an

eternal war trap are not mentioned]].

On the eve of World War I, however, Jewish political life in

Poland was well developed. The Bund had developed roots in

such worker centers as Warsaw and Lodz, while the [[racist]]

Zionists felt strong enough to challenge, albeit

unsuccessfully, the entrenched assimilationist leadership of

the Warsaw Jewish community.> (col. 738)

[[The time of the First World War 1914-1918 which would be

very interesting for Poland and it's Jewry is missing in the

article. It was a time of flight, destruction, death, hunger,

and disease (with many Jewish refugees since 1915 by

anti-Jewish propaganda always maintaining that Jews would be

the collaborators of the enemy), also 1919-1921 when the Red

army (financed by banks of the criminal "USA") was fought by

European armies (with many Germans, and with a Polish invasion

to Kiev) and at the end the Red army was fighting before

Warsaw (and was stopped by the French). Add to all this there

was a Jewish Communist government in Moscow so the anti-Jewish

propaganda invented the propaganda that Jews would all be

"Communists", and the "Christian" mob believed it, without

considering that there also were many impoverished Jews - and

discriminated Jews within the Communist system. This time was

also an important time for starting many Jewish organizations

like the Joint]].

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

731-732 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

733-734

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

735-736

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

737-738

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 728. Engraving of a Jew from Warsaw and his wife.

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col. 733-734. Caricature and music entitled,

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland,

vol. 13, col. 733-734. Nineteenth-century

caricature of Jews in the Polish militia

[[Jews are in the army but cannot understand

Polish]]. The text reads: " 'You Jews

listen to my command: Attention, present

arms!' 'What did he say? What did he say?'

Herschel thereupon asked the corporal."

Tel Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland,

vol. 13, col. 733-734. Nineteenth-century

caricature of Jews in the Polish militia

[[Jews are in the army but cannot understand

Polish]]. The text reads: " 'You Jews

listen to my command: Attention, present

arms!' 'What did he say? What did he say?'

Herschel thereupon asked the corporal."

Tel Aviv, I. Einhorn Collection](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne733-734-juden-in-armee-o-polnisch-19jh-20pr.jpg)

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13,

col. 728. Engraving of a Jew from Warsaw and his wife.

From L. Hollaenderski: "Les Israélites de

Pologne" [[Israelites in Poland]], Paris, 1846.

Jerusalem, Israel Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Poland, vol. 13, col.

728. Engraving of a Jew from Warsaw and his wife. From

L. Hollaenderski: "Les Israélites de Pologne"

[[Israelites in Poland]], Paris, 1846. Jerusalem, Israel

Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem](../d/EncJud_juden-in-Polen-d/EncJud_Poland-band13-kolonne728-jude-u-juedin-Warschau1846-36pr.jpg)