<The Marranos and the

Early Communities.

Among the Portuguese merchants in the Netherlands in the

17th century many were Marranos. It is known of one of

them, Marcus Perez, that he became a Calvinist and played

an important role in the Netherlands' revolt against

Spain. Without doubt there were many Marranos among the

20,000 merchants, industrialists, and scholars who left

Antwerp in 1585 for the Republic of the United Provinces.

Around 1590 the first indications of a Marrano community

are to be found in *Amsterdam, but its members did not

openly declare themselves as Jews. The Beth Jaäcob

community was founded in secret, apparently around 1600

(in the house of Jacob *Tirado). It was discovered in 1603

and the Ashkenazi rabbi Moses Uri b. Joseph *ha-Levi, who

had come from Emden the previous year, was arrested.

[since

1604: Jews in Alkmaar - since 1605: Jews in Rotterdam

and Haarlem - Jewish center Amsterdam]

Religious liberty was not granted in Amsterdam and

therefore the Marranos who had returned to Judaism, along

with newly arrived Jews from Portugal, Italy, and Turkey

[[Ottoman Empire]], tried to obtain a foothold somewhere

else. In 1604 they were granted a charter in Alkmaar, and

in 1605 in *Rotterdam and *Haarlem. Not only were they

accorded privileges regarding military service and the

Sabbath but they were also permitted to build a synagogue

and open a cemetery as soon as their numbers reached 50,

and to print (col. 975)

Hebrew books. Nevertheless, only a few availed themselves

of these privileges, and in spite of the difficulties most

Jews settled in Amsterdam; among them was the

representative of the sultan of Morocco, Don Samuel

*Palache.

[1608:

first Sephardi rabbi - no uniform policy toward the Jews

until 1795 - Jews in Dutch Brazil 1634-1654 - protection

for Dutch Jews abroad - Ashkenazim and Sephardim]

In 1608 a second community, Neveh Shalom, was founded by

Isaac Franco and in the same year the first Sephardi

rabbi, Joseph *Pardo, was appointed. As the legal status

of the Jews was not clearly defined the authorities were

asked by various bodies to clarify their attitude: the two

lawyers, Hugo *Grotius and Adriaan Pauw, were asked to

draw up special regulations for the Jews. However, in a

resolution of Dec. 13, 1619, the provinces of Holland and

West Friesland decided to allow each city to adopt its own

policy toward the Jews.

The other provinces followed this example, and this

situation remained in force until 1795. For this reason

the status of the Jews differed greatly in the various

towns. In Amsterdam there were no restrictions on Jewish

settlement, but Jews could not become burghers and were

excluded from most trades; however, no such disabilities

existed in several other towns. A large number of

Portuguese Jews, in search of greater economic

opportunities, took part in the expedition to *Brazil and

in 1634 Joan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen granted the charter

they had requested.

When the Netherlands was compelled to cede Brazil to

Portugal (1654) many Jews returned to Amsterdam. The Dutch

Republic, however, demanded that its Jews be recognized as

full citizens abroad and that no restrictive measure be

imposed on them if they visited a foreign country,

especially Spain (1657). The Ashkenazim also enjoyed the

rights which the Portuguese Jews had obtained in the

larger towns.

[18th

century: towns with Jewish liberty - Jewish robbers -

behavior certificate in most cities - power of the

parnasim - laws different from town to town]

In the first half of the 18th century in the eastern part

of the country also, in the area bordering Germany, small

communities could be founded with complete religious

liberty. Following on the activities of some Jewish

robbers, however, several cities enacted measures against

Jewish settlement: *Groningen (1710), *Utrecht (1713),

Gouda and the province of Friesland (1712), the province

of Overijssel (1724). *Amersfoort protested against one

such regulation in the province of Gelderland (1726), and

it was decided to introduce a certificate of good

behavior, which subsequently became a requirement in most

cities. Because this certificate was issued by the parnasim [[leaders]],

who also had to (col. 976)

guarantee the good behavior of the applicant, they

acquired considerable power over the newcomers.

Until *emancipation the legal position of the Jews

remained unclear since it was wholly dependent on local or

provincial authorities. In legal cases the Jews were

subject to the laws of the land and were judged in the

government courts. As they could not take the usual -

Christian - oath, a special formula was introduced by the

different provinces (the last in Overijssel in 1746), but

this had no derogatory content. Sometimes Jews even sought

the decision of Christian scholars in communities in the

case of serious internal conflicts, as in Amsterdam in

1673 where the Polish kehillah

[[community]] was ordered to join the German one (see

below) and when the authorities had to approve the

regulations of the kehillah.

Economic

Expansion.

[since

1610: Amsterdam as a world trade center - Jewish money

business and in the East India Company - sugar, silk,

tobacco, and diamond industry]

In spite of the restrictive regulations to which they were

subject (which included among other things exclusion from

the existing guilds), the Sephardi Jews were able to

acquire some economic importance. Thanks to their

knowledge of languages, administrative experience, and

international relationships, they played an important part

in the expanding economy of the young Republic of the

Netherlands, especially from 1610 onward when Amsterdam

became an established center of world trade.

After 1640 there was an increase in the number of current

account customers and the size of their accounts at the

discount bank (Wisselbank). In the second half of the 17th

century the Sephardim also occupied an important place

among the shareholders of the East India Company, the most

powerful Netherlands enterprise.

Portuguese Jews also acquired some prominence in industry,

especially in *sugar refineries, and the silk, tobacco,

and *diamond industries; although the latter had been

initiated by Christian polishers, in the course of time it

became an exclusively Jewish industry.

[Jewish

book printing]

However they became most celebrated for *book printing; in

1626 a large number of works were produced at a high

standard of printing for the day.

[Jews

as army suppliers, money lenders and speculators at

Amsterdam, The Hague, and Maarssen - colonial profits]

Among the richest Portuguese Jews, who were purveyors to

the army and made loans to the court, were Antonio Alvarez

*Machado, the *Pereira family, Joseph de Medina and his

sons, and the baron Antonio Lopez *Suasso. These and other

Portuguese Jews traded in stocks and shares from the

second half of the 17th century and probably constituted

the majority of traders in this field (see *Stock

Exchange). Such activity was centered in Amsterdam; the

only other important settlements were in The *Hague,

because of the proximity of the royal court, and Maarssen,

a village near Utrecht (which itself did not admit Jews)

which was the center of the country houses of the rich

Portuguese families. From Amsterdam the Portuguese Jews

took part in the economic exploration and exploitation of

old and new regions, mainly in the Western (col. 977)

hemisphere: Brazil, New Amsterdam, *Surinam, and Curaçao.

[18th

century: decline of the trade and economy - 54%

impoverished Jews by the end of the 18th century]

During the course of the 18th century trade declined and

economic activity concentrated to a growing extent on

stockjobbing. Daring speculations and successive crises

led to the downfall of important families, such as the De

*Pintos. The situation worsened after the economic crisis

of 1772 / 73 and became grave during the French occupation

(from 1794) when trade in goods practically came to a

standstill. Government monetary measures struck especially

at the rentiers [[renters?]], and by the end of the 18th

century the once wealthy community of Amsterdam included a

large number of paupers: 54% of the members had to be

given financial support.

[[Supplement: The Dutch regime in the colonies was

absolutely racist and harsh. The colonial trade brought

big profits first above all from the Spice Islands in the

today's Indonesia. But then the colonial trade changed by

the breakoff of trade monopolies, with plant cultivations

also in Africa and South America, and England became a big

concurrence with its "American" and African and Asian

possessions]].

Cultural

Activities of the Portuguese Community.

[Cultural

expansion of the Jewish community during the "Golden

Age" of the Netherlands - notable families]

The 17th century, the "Golden Age" of the Republic of the

Netherlands, was also a time of cultural expansion for the

Portuguese community. The medical profession was the most

popular, and there were often several physicians in one

family, as in the case of the Pharar family (Abraham "el

viejo", David, and Abraham), and the *Bueno family (no

less than eight, the most famous being Joseph, who in 1625

was called to the sickbed of Prince Maurits of Nassau, and

whose son, Ephraim *Bueno, was painted by Rembrandt),

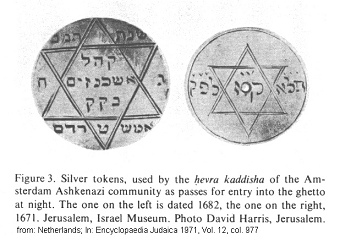

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Netherlands, vol.12, col.975:

Hezekiah Bueno, portrait by Rembrandt: Ephraim Hezekiah

Bueno,

Amsterdam physician, writer, and publisher. Etching,

school of Rembrandt. Amsterdam, Empire Museum

(Rijksmuseum)

and the De Meza,

*Aboab, and De Rocamora families. The most celebrated

physicians were *Zacutus Lusitanus and Isaac *Orobio de

Castro. From 1655 onward there were physicians who had

completed their studies in Holland, (col. 978)

especially in Leiden and Utrecht. They were free to

practice their profession among non-Jews also, but they

were required to take a special oath.

[Discriminations

are not followed in the guild of surgeons and

pharmacists]

In Amsterdam, where the surgeons and pharmacists (who

needed no academic training) were organized into guilds,

Jews could not be officially admitted to these professions

(according to the regulation of 1632). Nevertheless they

set up in practice, with the result that in 1667 they were

forbidden to sell medicine to non-Jews. This regulation

was ignored, and so when a new regulation was issued in

1711 the restrictive clause was not included.

[Jewish

artists in Holland: illuminators, engravers, writers]

Many Portuguese Jews were artists (notably the illuminator

Shalom *Italia and engraver Jacob Gadella) and writers,

mainly of poems and plays in Spanish and Portuguese; there

were even two special clubs where Spanish poetry was

studies. The best-known poet was Daniel Levi (Miguel) de

*Barrios, the first historian of the Marrano settlement in

the Netherlands.

[Community

life: Jewish studies, literature, Torah school and

teachers]

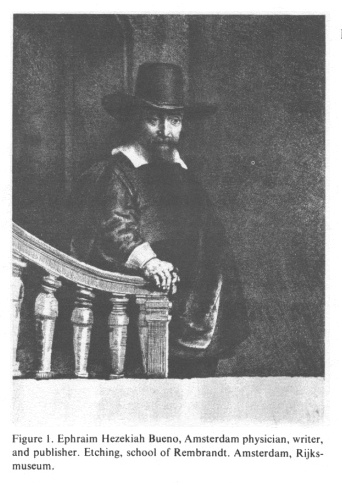

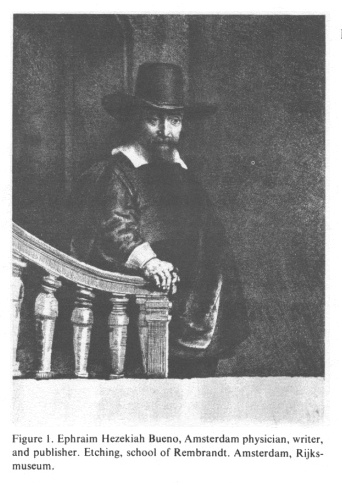

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Netherlands, vol.12, col.976: Dutch

hanukkha lamp: Dutch Hanukkah lamp, 17th century,

brass, 13 1/2 x 13 inches (34.5 x 33 cm.). Cecil Roth

Collection. Photo Werner Braun, Jerusalem

More interesting,

however, was the high level of study of Judaism and its

literature from the early days of the settlement, and this

in spite of the fact that large numbers of the newcomers

had returned to Judaism at an advanced age. In order to

teach the younger generation about Judaism the two kehillot

[[communities]] in Amsterdam, Beth Jaäcob and Neveh

Shalom, founded in 1616 the Talmud Torah or Ets Haim yeshivah [[religious

Torah school]]. Through the efforts of teachers from the

Sephardi Diaspora, such as Saul Levi *Morteira and Isaac

Aboab da *Fonseca, the yeshivah became renowned. Among the

later teachers were *Manasseh Ben Israel, Mosses Raphael

de *Aguilar, and Jacob *Sasportas.

[Jewish

book printing in Holland]

The facilities for printing books (see above) contributed

to the high level of scholarship, and the independent

production (col. 979)

of scientific, theological, and literary works in Hebrew

also developed. The most important writers were Moses

*Zacuto, Solomon de *Oliveyra, Joseph *Penso de la Vega,

and in the 18th century David *Franco-Mendes.

[Inner

quarrels about the Jewish religion, leadership and

deviators - Shabbatean movement]

The return of the Marranos to Judaism was accompanied by

conflicts about the nature of their religion. In 1618 a

group of strictly Orthodox Jews left Beth Jaäcob and

founded the Beth Jisrael community because they did not

accept the liberal leadership of the parnas [[president]]

David Pharar. Soon after, Uriel da *Costa's attack on

Orthodox Judaism caused an upheaval throughout the whole

*Marrano Diaspora. The most famous case was that of Baruch

*Spinoza, who was banned from the kehillah

[[community]] for his blasphemous opinions.

At this period - as among Sephardim elsewhere - Lurianic

*Kabbalah had many followers in Amsterdam, which explains

the enthusiasm for *Shabbetai Zevi that prevailed in the

community in 1666. The Shabbateans maintained a strong

influence for a long period and during the chief rabbinate

of Solomon *Ayllon there was a serious conflict in which

the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Amsterdam Zevi Hirsch

*Ashkenazi (Hakham Zevi) was involved (1713). The failure

of the Shabbatean movement on the one hand and the power

and wealth of the kehillah (all three congregations united

in 1639) on the other led to an ever-increasing isolation

from the rest of the Jewish world and to a rapprochement

with Dutch society.

The turning point was the founding of the famous Esnoga

(synagogue), inaugurated in 1675, which subsequently

dominated Sephardi community life.

The

Ashkenazim.

[17th

century: Ashkenazim Jews arriving from Germany, Poland,

and Lithuania - forced union since 1673 - places of

settlement - some trade and poverty]

Unlike the Sephardim, the Ashkenazim spread throughout the

whole Republic of the Netherlands, although their main

center was also in Amsterdam. The first Ashkenazim arrived

in Amsterdam around 1620, establishing their first

congregation in 1635. The first emigration was from

Germany but in the second half of the 17th century many

Jews also came from Poland and Lithuania: they founded a

separate community (1660), but in 1673, after disputes

between the two, the municipal authorities ordered it to

amalgamate with the German one.

[Growing

Jewish community during the 17th and 18th century]

The community grew rapidly, outnumbering the Portuguese in

the 17th century though remaining in a subservient

position until the end of the 18th century. During the

17th century, the most important communities outside

Amsterdam were in Rotterdam and The Hague. At that time

Jews also settled in several towns in the provinces

bordering Germany: Groningen, Friesland, Overijssel, and

Gelderland. In spite of restrictive measures, their number

increased in the 18th century, and they extended to a

large number of smaller towns. There were a few very rich

Ashkenazi families, such as the *Boas (The Hague), the

Gomperts (Nijmegen and Amersfoort), and the Cohens

(Amersfoort), but the overwhelming majority earned a

meager living as peddlers, butchers, and cattle dealers.

In Amsterdam the economic difficulties of the Ashkenazi

Jews were even more acute and the poverty among them even

greater. Apart from the diamond and book printing

industries, very few trades were open to them and the

majority engaged in trading in second-hand goods and

foodstuffs. Foreign trade, mainly in money and shares, was

concentrated in Germany and Poland. Culturally the

Ashkenazi yishuv

[[Jewish population]] depended on Germany and Eastern

Europe, from where most of their rabbis came. The

colloquial language was Yiddish, increasingly mixed with

Dutch words.

Contact with the non-Jewish population was superficial,

except among the very small upper class which arose in the

second half of the 18th century.> (col. 980)

|

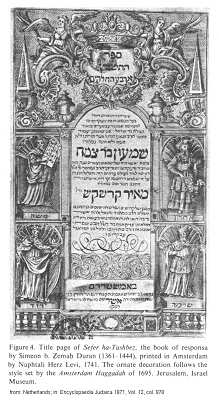

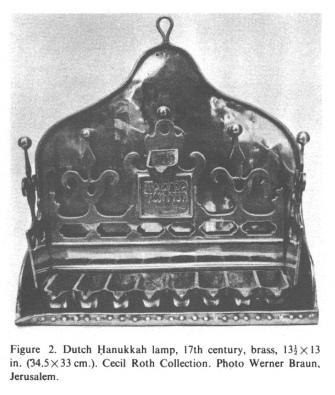

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Netherlands, vol.

12, col. 978, Duran: Tashbez: Title page of Sefer ha-Tashbez,

the book of response by Simeon b. Zemah Duran

(1361-1444), printed in Amsterdam by Naphtali

Herz Levi, 1741. The ornate decoration follows

the style set by the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695.

Jerusalem, Israel Museum.

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Netherlands, vol.

12, col. 978, Duran: Tashbez: Title page of Sefer ha-Tashbez,

the book of response by Simeon b. Zemah Duran

(1361-1444), printed in Amsterdam by Naphtali

Herz Levi, 1741. The ornate decoration follows

the style set by the Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695.

Jerusalem, Israel Museum.

|

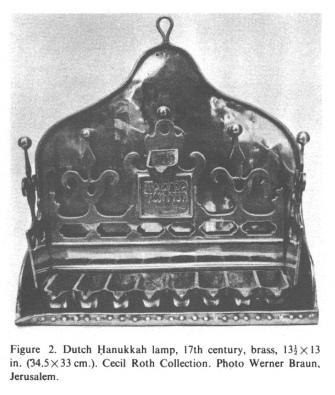

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Netherlands, vol. 12, col. 977, coins: Silver tokens, used by the hevra kaddisha (community) if the Amsterdam Ashkenazi community as passes for entry into the ghetto at night. The one on the left is dated 1682, the one on the right 1671. Jerusalem, Israel Museum. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem