Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Russia 02: Russian Czarist Antisemitism 1772-1881 - student development

Czarist rule in Eastern Europe after the Polish partitions - discriminations in the Pale of Settlement - different developments with tradition and enlightenment - manipulations with schooling and professions - Cantonists and expulsions from villages - military draft - cultural developments and emancipation hopes

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14

from: History; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 8

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

[18th century: Expansion of Russia - Czarist Russian rule]

<With the partitions of Poland at the end of the 18th century [[1772, 1793, 1795]] most of the Jews of Lithuania and the Ukraine, and at the beginning of the 19th century also those of Poland, found themselves under [[Czarist anti-Semitic]] Russian rule. During the 19th and 20th centuries Russian Jewry was, however, essentially an organic continuity of the Jewry of Poland and Lithuania in the ethnic as well as cultural respects. (col. 434)

[[Czarist Rule was absolutely anti-Semitic and the "Christian" populations were following it up to many pogroms and boycotts since 1881 which caused emigration and the idea of emigration to Palestine by racist Zionism]].

Within the Russian Empire: First Phase (1772-1881). [Jews are the middle class between landowners and peasants]

The Jews who lived in the regions annexed by Russia (the "Western Region" and the "Vistula Region" in the terms of the Russian administration) formed a distinct social class. In continuation of their economic functions in Poland-Lithuania, they essentially formed the middle class between the aristocracy and the landowners on the one hand, and the masses of enslaved peasants on the other. Many of them earned their livelihood from the lease of villages, flour mills, forests, inns, and taverns. Others were merchants, shopkeepers, or hawkers [[peddlers going from house to house]].

The remainder were craftsmen who worked for both landowner and peasant. Some of them lived in townlets which had mostly been founded on the initiative of the landowners and served as centers for the merchants and the craftsmen, while others lived in villages or at junctions of routes. It is estimated that the occupational structure of the Jews at the beginning of the 19th century was as follows:

Table 1 [Jewish professions in Russia at the beginning of the 19th century] Occupation

%

Innkeeping and leases xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

30%xxxxxxxxx

Trade and brokerage

30%xxxxxxxxx Crafts

15%xxxxxxxxx Agriculture

1%xxxxxxxxx No fixed occupation

21%xxxxxxxxx Religious officials

3%xxxxxxxxx from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14, col. 435

[Heavy discrimination of the Jews under Czarist rule in the Pale of Settlement - split between Hasidim and Mitnaggedim - different Jewish courts]

The economic position of the Jews steadily deteriorated with their confinement to the *Pale of Settlement (see below), their rapid growth in numbers, and consequent gradual proletarianization and increasing pauperization. The autonomy of the Jewish community was at first recognized. The Jews maintained their traditional educational network.

When they came under Russian rule, many of the communities had become heavily in debt. Economic difficulties, the burden of taxes - in particular the meat tax (see *korobka) - and social tensions drove many Jews to abandon the townlets and settle in villages or on the estates of noblemen.

During the period of their transfer to Russian domination, the Jews of the "Western Region" were involved in a grave conflict between the *Hasidim [[strongly orthodox Jews]] and the *Mitnaggedim [[opponents]]. Once the Russian government gained control of this region, it became involved in this conflict. Complaints and slander even resulted in the arrest of *Shneur Zalman of Lyady in 1798 and his transfer to St. Petersburg for interrogation. The various hasidic "courts" (the most important of which were those of *Lubavichi-Lyady, *Stolin, Talnoye, *Gora-Kalwaria, *Aleksandrow), as well as the yeshivot [[religious Torah school]] of the Mitnaggedic-type in Lithuania (the most important in the townlets of *Volowhin, founded in 1803, *Mir, *Telz (Telsiai), Eishishki (Eisiskes), and *Slobodka; see also *Maggid; *Musar movement) combined to form a flourishing and variegated Jewish culture.

[Jewish settlement on Black Sea shore and Dnieper provinces since 1791 - extension by Bessarabia since 1812 and Polish kingdom since 1815 - 1/9 Jews - Jewish settlers in Courland, in Caucasus and in Russian Central Asia]

CRYSTALLIZATION OF RUSSIAN POLICY TOWARD THE JEWS.

From the beginning of its annexation of the Polish territories the Russian government adopted the attitude of viewing the Jews there as the "Jewish Problem", to be (col. 435)

solved ultimately by their "assimilation or expulsion. During the first 50 years after incorporation within the borders of the empire, the general tendency of the government was to maintain the status of the Jews as it had been under Polish rule, while adapting it to the Russian requirements. A decree of 1791 confirmed the right of residence of the Jews in the territories annexed from Poland and permitted their settlement in the uninhabited steppes of the Black Sea shore, conquered from Turkey at the close of the 18th century, and in the provinces to the east of the R. Dnieper (*Chernigov and *Poltava) only. Thus crystallized the Pale of Settlement, which took its final form with the annexation of Bessarabia in 1812, and the "Kingdom of Poland" in 1815, extending from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and including 25 provinces with an area of nearly 1,000,000 sq km (286,000 sq mi [[miles]]).

the Jews formed one-ninth of the total population of the area. Jewish residence was also authorized in *Courland and, at a later date, in the Caucasus and Russian Central Asia to Jews who had lived in thee regions before the Russian conquest.

[The Czarist regime blames the Jews for their poverty]

In the regions annexed from Poland the Jews were caught up in the dilemma facing czarist rule there. The regime, whose power rested on the nobility, refrained [[denied]] from throwing the responsibility for the miserable plight of the mainly Orthodox peasants onto the Christian landowners, mainly of the Polish Catholic nobility, preferring to blame the Jews in the villages; It accepted the claim of the local nobility and officials allied to it that the Jews were causing the exploitation of the peasants (see G.R. *Derzhavin). The Jewish autonomy and independent culture added to this antagonism, as being alien [[strange]] to the Russian centralist regime and Christian-feudal culture.

[[Add to this there was the anti-Semitic Orthodox "Christian" church spreading hatred against the Jews. This is never mentioned in Encyclopaedia Judaica]].

[1804: First "Jewish Statute": integration into the Russian school system - prohibition of residence in villages, prohibition of leasing activity, prohibition of sale of alcoholic beverages - support for peasants and factories]

These concerns animated the first "Jewish Statute" promulgated in 1804. Its first article authorized the admission of the Jews to all the elementary, secondary, and higher schools in Russia. Jews were also authorized to establish their own schools, provided that the language of instruction was Russian, Polish, or German. [[So the Jewish children went to Jewish schools and not to the Russian schools, see below 1840s]].

The most important of the economic articles of the statute was

-- the prohibition of the residence of Jews in the villages,

-- of all leasing activity in the villages,

-- and of the sale of *alcoholic beverages to the peasants.

This struck at the source of livelihood of thousands of Jewish families.

The legislation therefore declared that Jews would be allowed to settle as peasants on their lands or on the lands which would be allocated [[distributed]] to them by the government. Government support was also promised to factories which would employ Jewish workers and to craftsmen.

In 1817 Alexander I outlawed the *blood libel which had caused terror and suffering to the Jewish communities in the 18th century.

[Delay of the implementation of the Statute and Napoleon difficulties - trials of conversion]

A short while after the publication of the "Jewish Statute", the expulsion of the Jews from the villages began, as did their settlement in southern Russia. It was however soon evident that agricultural settlement (see *agriculture) could not rapidly absorb the thousands of Jewish families who had been removed from their livelihoods. The expulsion order was therefore delayed, this being also due to the political and military situation in Russia during the war against Napoleon.

Only in 1822 was the systematic expulsion of the Jews from the villages, especially in the provinces of Belorussia, resumed. An unsuccessful attempt was also made to induce [[bring]] the Jews to convert to Christianity by promises of *emancipation and government support for their settlement on the land.

[1827: military Cantonist system for Jewish children with quota system in Lithuania and Ukraine - further expulsion of the Jews from villages and from Kiev - 1843: prohibition of Jews in new villages and 50 versts border zone - agricultural settlements supported]

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 439-440, Cantonist oath sworn in the synagogue of Pinsk, 1829

UNDER NICHOLAS I.

The reign of *Nicholas I (1825-55) forms a somber [[dark]] chapter in the history of Russian Jewry. This czar, notorious in Russian history for his cruelty, sought to solve the "Jewish Problem" by suppression and (col. 436)

coercion [[dictates]]. In 1827 he ordered the conscription of Jewish youths into the army under the iniquitous *Cantonists system which conscripted youths aged from 12 to 25 years into military service, those aged under 18 were sent to special military schools also attended by the children of soldiers. This law caused profound demoralization within the communities of Lithuania and the Ukraine (it did not apply to the Jews of the "Polish" provinces).

Nobody wished to serve in the army in the prevailing [[dominating]] inhuman conditions and the "trustees" responsible on behalf of the communities for filling the quotas of conscripts were compelled to employ "snatchers" ("khapers") to seize the youngsters. The military obligations of the Jews in Russia brought no alleviation [[relief]] of their condition in other spheres, and the expulsions of Jews from the villages continued with regularity. The Jews were also expelled from Kiev, and any new settlement of Jews in the towns and townlets within a distance of 50 versts of the country's borders was prohibited in 1843.

On the other hand, the government encouraged agricultural settlement among Jews. The settlers were exempted from military service. Many Jewish settlements were established on government and privately owned lands in southern Russia and other regions of the Pale of Settlement. (col. 438)

[[Jews were systematically humiliated by converting them into peasants]].

[1840s: network of special schools for Jews financed by "candle tax" - Lilienthal as government agent - school decree and school system against (racist) Talmud 1844]

During the 1840s the government began to concern itself with the education of the Jews. Since the Jews had not made use of the opportunity which had been given to them in 1804 to study in the general schools, the government decided to establish a network of special schools for them. The maintenance of these schools would be provided for by a special tax (the "*candle tax") which would be imposed on them. In order to pave the way for this activity, the government sent Max *Lilienthal, a German Jew employed as teacher in the school established in Riga by the local maskilim [[followers of the Haskalah, enlightenment Jews, secularists]], on a reconnaissance trip through the Pale of Settlement.

During 1841-42 Lilienthal visited the large communities of the Pale of Settlement - Vilna, Minsk, Berdichev, Odessa, and Kiev. He was received with suspicion by the Jewish masses, who regarded the project to establish government schools for Jews as a medium for the estrangement of their children from their religion.

In 1844 a (col. 439)

decree ordering the establishment of these schools, whose teachers would be both Christians and Jews, was issued. In secret instructions which accompanied the decree it was declared that "the purpose of the education of the Jews is to bring them nearer to the Christians and to uproot their harmful beliefs which are influenced by the Talmud."

Lilienthal became aware of the government's intentions and fled from Russia. The government established this network of schools which depended for instruction upon a handful of maskilim and at the head of which were the seminaries for rabbis and teachers of Vilna and *Zhitomir. These institutions, to which the Jewish masses shrank [[minimized]] from sending their children, served as the cradle [[base]] for a class of Russian-speaking maskilim which was to play an important role in the lives of the Jews during the following generations.

[1844: new Jewish communal structure - duties of the community to the Czar (tax, registrations, sermons) - prohibition of Jewish sidelocks and clothes]

In 1844 the government abolished the Polish-style (col. 440)

communities but was nevertheless compelled to recognize a limited communal organization whose function it was to watch over the conscription into the army and the collection of the special taxes - the korobka and "candle tax". The community was also responsible for the election of the *kazyonny ravvin ("government-appointed rabbi"), whose function it was to register births, marriages, and deaths and to deliver sermons on official holidays extolling the government. A law was also issued prohibiting Jews from growing pe'ot ("sidelocks") and wearing their traditional clothes.

["Useful" for work - "non-useful" Jews for the army since 1851 - protest of west European Jews - agent Montefiore without success - Crimean War with tripling the Jewish quota in the army - kidnapping]

The next stage of the program of Nicholas I was the division of the Jews of his country into two groups: "useful" and "non-useful". Among the "useful" ranked the wealthy merchants, craftsmen, and agriculturalists. All the other Jews, the small tradesmen and the poorer classes, constituted the "non-useful" and were threatened with general conscription into the army, where they would be trained in crafts or agriculture. This project encountered the opposition of Russian statesmen and aroused the intervention of the Jews of Western Europe on behalf of their coreligionists. In 1846 Sir Moses *Montefiore traveled from England to Russia for this purpose. The order to classify the Jews according to these categories was nevertheless issued in 1851.

The Crimean War delayed its application but amplified the tragedy of military conscription. The quota was increased threefold and the "snatchers" were given a free hand to seize children, and travelers who did not possess documents, and hand them over to the army. The reign of Nicholas I came to an end with the memory of those days of intensified kidnapping.

[Reforms since 1855]

UNDER ALEXANDER II.

The reign of *Alexander II (1855-81) is connected with great reforms in the Russian regime, the most important of which was the emancipation of the peasants in 1861 from their servitude to the landowners. (col. 441)

Toward the Jews, Alexander II adopted a milder policy with the same objective as that of his predecessor of achieving the assimilation of the Jews to Russian society. He repealed the severest of his father's decrees (including the Cantonists system) and gave a different interpretation to the classification system by granting various rights - in the first place the right of residence throughout Russia - to selected groups of "useful" Jews, which included wealthy merchants (1859), university graduates (1861), certified craftsmen (1865), as well as medical staff of every category (medical orderlies and midwives).

The Jewish communities outside the Pale of Settlement rapidly expanded, especially those of St. Petersburg and Moscow whose influence on the way of life of Russian Jewry became important.

[1874: general draft to the army - exceptions for Russian educated Jews - no Jewish officers - Jews in official and cultural life - and new dispute about Jews in the society - nationalist wave after Balkan war since 1878]

In 1874 general draft to the army was introduced in Russia. Thousands of young Jews were now called upon to serve in the army of the czar for four years. Important alleviations [[relief]] were granted to those having a Russian secondary-school education. This encouraged the stream of Jews toward the Russian schools. At the same time Jews were not admitted to officers' rank.

The general atmosphere the new laws engendered was of no less importance than the laws themselves. The administration relaxed its pressure on the Jews and there was a feeling among them that the government was slowly but surely proceeding toward the emancipation of the Jews. Jews began to take part in the intellectual and cultural life of Russia in journalism, literature, law, the theater, and the arts; the number of professionals was then very small in Russia, and Jews soon became prominent among their ranks in quantity and quality. Some Jews distinguished themselves, such as the composer Anton *Rubinstein (baptized in childhood), the sculptor Mark *Antokolski, and the painter Isaac *Levitan.

This appearance of Jews in economic, political, and cultural life immediately aroused a sharp reaction in Russian society [[and it can be admitted that it was provoked by the anti-Semitic Orthodox "Christian" church]]. The leading opponents of the Jews included several of the country's most prominent intellectuals, such as the authors Ivan Aksakov and Fyodor Dostoyevski. The attitude of the liberal and revolutionary elements in Russia toward the Jews was also lukewarm. The Jews were accused of maintaining "a state within a state" (the enemies of the Jews found support for this opinion in the work of the apostate [[converted Jew]] J. *Brafman, "The Book of the Kahal", published in 1869), and of "exploiting" the Russian masses; even the blood libel was renewed by agitators (as that of Kutais in 1878).

However, the principal argument of the hatemongers was that the Jews were an alien element invading the areas of Russian life, gaining control of economic and cultural positions, and a most destructive influence. Many newspapers, led by the influential [[newspaper]] Novoye Vremya [["New Times"]], engaged in anti-Jewish agitation.l The anti-Jewish movement gained in strength especially after the Balkan War (1877-78), when a wave of Slavophile nationalism swept through Russian society.

[Medical progress minimizes child mortality - 2.35 to 5 mio. Jews - the Czars see the "Jewish problem" rising]

POPULATION GROWTH.

One of the factors which influenced the position of the Jews was their high natural increase, due to the high birthrate and the relatively low mortality among children - the result of the devoted care of Jewish mothers as well as of medical progress. The number of Jews in Russia which in 1850 had been estimated at 2,350,000 rose to over 5,000,000 at the close of the 19th century, notwithstanding a considerable emigration abroad. Governmental commissions appointed to deal with the "Jewish Problem" received instructions to seek methods for the reduction of the number of Jews in the country.

[Population growth and new crafts and workers professions - new wealthy Jews in industrialization and in the banking system - poor masses by lack of land - emigration and migration movement to Ukraine]

ECONOMIC POSITION.

The natural growth resulted in increased competition in the traditionally Jewish occupations. The numbers of small shopkeepers, *peddlers, and (col. 442)

brokers rose steadily. Many joined the craftsmen's class, a step which in those days was considered a fall in social status. A Jewish proletariat began to develop; it included workshop and factory-workers, daily workers, male and female domestics, and porters. At the same time there also emerged a small but influential class of wealthy Jews who succeeded in adapting to the requirements of the Russian Empire and established contacts with government circles. The first members of this class were contractors engaged by the government in the building of roads and fortresses, or purveyors [[suppliers]] to army offices and units. During the reign of Nicholas I many Jews engaged in leasing the sale of alcoholic beverages which had become a government monopoly.

From the 1860s Jews played an important role in the construction of railroads and the development of mines, industry (especially the foodstuff and textile industries), and export trade (timber; grain). They were among the leading founders of the banking network of Russia. This class of Jews was prominent in St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Kiev, and Warsaw. This upper bourgeoisie, headed by the *Guenzburg and *Poliakov families, considered themselves the leaders of Russian Jewry. They were closely connected with Jews who had acquired a higher education and had penetrated the Russian intelligentsia and the liberal professions (lawyers, physicians, architects, newspaper editors, scientists, and writers).

The wealth and the status of this small class was however unable to alleviate [[relief]] the suffering of the destitute masses.

After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, the serious lack of land for the Russian peasants themselves became evident and the government ceased to encourage Jewish settlement on the land. Emigration became the only outlet. Until the 1870s the migration was mainly an internal one, from Lithuania and Belorussia in the direction of southern Russia. While in 1847 only 2.5% of Russian Jews lived in the southern provinces, the proportion had increased to 13.8% in 1897. Important new communities appeared in this region: Odessa (about 140,000 Jews), Yekaterinoslav (*Dnepropetrovsk), Yelizavetgrad (*Kirovograd), *Kremenchug, etc.

The famine in Lithuania at the end of the 1870s encouraged emigration toward Western Europe and the United States.

HASKALAH IN RUSSIA. [Jewish enlightenment movement and representatives and institutions]

From the middle of the 19th century *Haskalah became influential among Russian Jewry. Its first manifestations, combined with signs of assimilation, appeared in the large commercial cities (Warsaw, Odessa, Riga). Among the Russian adherents of Haskalah there was a trend to preserve Judaism and its values; hence they tended to seek changes based mainly on a thread of continuity. Although there were also circles which stood for complete assimilation and absorption in Eastern Europe (the "Poles of the Mosaic Faith" of Poland, nihilist and socialist circles in Russia), the majority of the maskilim sought a path which would preserve the national or national-religious identity of the Jews, while some of them even developed an indubitable nationalist ideology (Perez *Smolenskin).

The herald of the Haskalah in Russia was the author Isaac Dov (Baer) *Levinsohn. In his Te'udah be-Yisrael (Vilna, 1828), he formulated an educational and productivization program. The most distinguished pioneers of Haskalah in Russia were the author Abraham *Mapu, the father of the Hebrew novel, and the poet Judah Leib *Gordon. Even though the maskilim were at first opposed to Yiddish, which they sought to replace by the language of the country, some of them later created a secular Yiddish literature (I.M. *Dick; *Mendele Mokher Seforim; and others).

At the initiative of the maskilim there also emerged a Jewish press in Hebrew (*Ha-Maggid, founded in 1856; *Ha-Meliz); in Yiddish (*Kol Mevasser); and in Russian (*Razsvet, founded in 1860; Den). The Hevrat Mefizei Haskalah (col. 443)

("*Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia"), founded in 1863 by a group of wealthy Jews and intellectuals of St. Petersburg, was an important factor in spreading Haskalah and the Russian language among Jews.

These books and newspapers infiltrated into the battei-midrash [[Houses of Learning]] and the yeshivot [[religious Torah schools]],influencing students to leave them. Severe ideological disputes broke out in many communities, often between father and son, rabbi and disciples. The government assisted the spread of Haskalah as long as its adherents supported loyalty to the czarist regime (as expressed by J.L. Gordon - "to your king a serf") and cooperated in promoting educational and productivization programs as well as in its opposition to the traditional leadership.

[Split of Jewry by the Russian school system since 1874]

By the 1870s the activity of the maskilim [[enlightenment Jews]] began to bear fruit. The mass of Jewish youth streamed to the Russian-Jewish and general Russian schools. [[This was not only the Haskalah effect but also provoked by the law of 1874 that Jews of Russian education had relief in the army]]: The general conscription law of 1874 encouraged this process, and thus began the estrangement of the intellectual youth from its people and Jewish affairs - to the despair [[desperation]] of the nationalist wing of the Haskalah which resigned itself to this situation.

However the rise of the anti-Semitic movement within Russian society during the late 1870s (see above) resulted in a nationalist awakening among this youth.

[[It can be admitted that there was growing an envy in the Russian society about the schooling and military law that Jews got relief in the army by visiting a Russian speaking school. This could not be accepted by the Russians, and the Czar used Antisemitism for his purposes]].

This was expressed in the development of a Jewish-Russian press and literature dealing with the problems of the Jews and Judaism (Razsvet; Russkiy Yevrey; *Voskhod).> (col. 444)

Jewish student development in racist czarist Russia before 1881

Jewish education standard higher than Russian education standard - Jews in Russian high schools - numerus clausus - studies abroad - Jewish students with revolutionary tendencies and in the intelligentsia

from: History; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 8

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

[Jewish education standard higher than Russian education standard - more Jews in Russian high schools - numerus clausus - studies abroad]

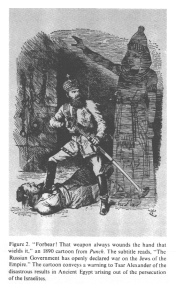

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 437, cartoon about the war

against the Jews in Russia and who will win it

The evil of stereotypes and vulgarization increasingly made itself felt in its impact on Jewish life from the 1880s. The ruling circles of the [[criminal "Christian" racist]] czarist state and society adopted a policy of open anti-Semitism in order to divert the resentment of the masses to the Jews. These circles were considerably disturbed and angered by a phenomenon of their own creation that had appeared in Jewish society.

In the 1860s and 1870s Jews had been promised alleviations [[relief]] and rewards as a prize for acquiring secular education and skills in line with the government policy of remolding them into satisfactory citizens. The Russian government, however, had no conception of the strength of the cultural traditions of veneration of study and respect for the student among Jews. Jewish society in Russia, by the criteria of its own culture, was considerably more educated and intellectualized than Russian society. When the aspiration of Jewish youths now turned toward secular learning and Russian culture, the ruling circles were dismayed by the "flood" of Jews that threatened their high schools, universities, and consequently, the composition of the Russian intelligentsia.

They turned increasingly to the policy of severely restricting the numbers of Jewish students by imposition of the *numerus clausus. They also applied higher standards to Jewish pupils in Russian high schools and made more exacting demands on them.

Frustration and anger swept the youth who were eager to learn outside the sphere of their own traditions, who had been ready at first for assimilation and service to the Russian state, and who were now being punished for revealing the high cultural level of their society and their own individual abilities.

The trend toward academic education and free entry to the professions could not be halted among the Jews of the Pale of Settlement. Thousands who were not accepted at Russian universities went westward for their education, mainly to Germany and Switzerland. In university cities in these countries Jews formed a large part of the "Russian student colonies". They knew that, having obtained a degree, back in Russia they would still be discriminated against because of their Jewishness.

[Russian Jewish students with revolutionary tendencies - Jewish domination of Russian intelligentsia]

The state thus fostered the radicalization among Jewish students and a Jewish intelligentsia, who identified themselves with the revolutionary struggle for freedom and a better society in Russia. Hence the proportion of Jewish intellectuals among the leading cadres of the various Russian revolutionary parties grew increasingly larger, and was much greater than their proportion to the general population and at total variance with the social background of their homes. The [[criminal racist "Christian"]] authorities and their supporters were quick to clutch at the stereotype of the "Jewish subversive spirit" in opposing the Jews, and pointed out to them - by discriminatory measures as well as by massacres - that the western border was open to Jews to emigrate (while the eastern border of the Pale of Settlement remained closed). The government thus hoped both to solve "the Jewish question" and to weaken the revolutionary movement at one stroke. (col. 734)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

^

![Encyclopaedia Judaica

(1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 437-438, three

Jews (with beards, right) in a Tatar market

in the Crimea. From a series of drawings by

the Leipzig engraver, Geissler, depicting

the journey of the privy councilor of the

Palatinate [[Pfalz]] through Old Russia,

1794-1802 Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia,

vol. 14, col. 437-438, three Jews (with

beards, right) in a Tatar market in the

Crimea. From a series of drawings by the

Leipzig engraver, Geissler, depicting the

journey of the privy councilor of the

Palatinate [[Pfalz]] through Old Russia,

1794-1802](EncJud_Russia-d/EncJud_Russia-band14-kolonne437-438-Krim-markt-ende-18jh-35pr.jpg)