Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Russia 03: Russian pogrom habit 1881-1914

Murdered czar and Russian pogrom habit since 1881 - emigration - self-defense since 1903 - new Jewish organizations - census 1897 - radical Jewish movements Socialists, Bund and racist Zionism - Jewish cultural developments in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian

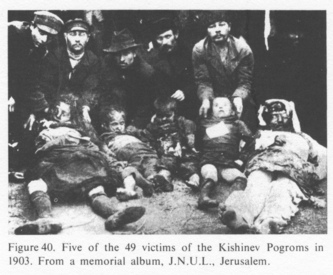

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): History, vol. 8, col. 735: Jewish victims of Kishinev pogrom of 1903

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14

from: History; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 8

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

[1881: Czar murdered - pogroms - and the new czar Alexander III also supports the pogroms - numerus clausus against Jews - and radicalization of the Jews]

Within the Russian Empire: Second Phase (1881-1917).

<The year 1881 was a turning point in the history of the Jews of Russia. In March 1881 revolutionaries assassinated Alexander II.>

[[This was a bomb attack of the revolutionary group Narodnaja Wolja. The aim had been a more democratic Russia [1] ]].

<Confusion reigned throughout the country. The revolutionaries called on the people to rebel. The regime was compelled to protect itself, and the Russian government found a scapegoat: the notion was encouraged that the Jews were responsible for the misfortunes of the nation. Anti-Jewish riots (*pogroms) broke out in a number of towns and townlets of southern Russia including Yelizavetgrad (Kirovograd) and Kiev. These disorders consisted of looting, while there were few acts of murder or rape.

Similar pogroms were repeated in 1882 (*Balta, etc.); in 1883 (Yekaterinoslav, now Dnepropetrovsk, *Krivoi Rog, Novo-Moskovsk, etc.); and in 1884 (Nizhni-Novogorod, now *Gorki). The indifference to - and at times even sympathy for - the rioters on the part of the Russian intellectuals shocked many Jews, especially the maskilim [[enlightenment Jews]] among them.

[[It can be admitted that the anti-Semitic Orthodox "Christian" church played a big role in this pogrom wave]].

Revolutionary circles which hoped to transform these disorders into a revolt against the landowners and government also supported the rioters. The new czar, *Alexander III (1881-94), and his cabinet underlined these trends in their policy toward the Jews. Provincial commissions were appointed in the wake of the pogroms to investigate their causes. In the main these commission stated that "Jewish exploitation" had caused the pogroms. Based on this finding, the "Temporary Laws" were published in May 1882 (see *May Laws). These prohibited the Jews from living in villages and restricted the limits of their residence to the towns and townlets. [[...]]

The pogroms were indeed halted in 1884 but instead administrative harassment of Jews became worse. [[...]]

Among the assassins was one Jewish girls who played a quite minor role, but reactionary newspapers almost immediately began to whip up anti-Jewish sentiment. The government probably did not directly organize these riots, but it stood aside as Jews were murdered and pillaged, and the regime used the immediate occasion to enact anti-Jewish economic legislation in 1882 (the *May Laws).

The situation continued to deteriorate to such a degree that in the next reign Czar *Nicholas II gave money to the anti-Semitic organization, the Black Hundreds, and made no secret to his personal membership, and that of the crown prince, in that organization (see *Union of Russian People).

(from: Encyclopaedia Judaica: Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 123)

In an attempt to halt the flood of Jews now seeking entry to secondary schools and universities, and their competition with the non-Jewish element, the number of Jewish students in the secondary and higher schools was limited by law in 1886 to 10% in the Pale of Settlement and to 3-5% outside it.

This *numerus clausus did much to accomplish the radicalization of Jewish youth in Russia. Many went to study abroad; others were able to enter Russian schools only if showing outstanding ability. All became embittered and disillusioned with the existing Russian society.>

(Russia, col. 444)

<In 1881 one wave of massacres broke over southern [[racist "Christian" czarist]] Russia that hit about 100 communities. From then on massacres as well as arson [[put fire]] in the Jewish townships, which were built of wood, became endemic in [[racist "Christian"]] czarist Russia.>

(History, col. 735)

[1891: expulsion of the Jews from Moscow and from villages and villages - press campaign]

<In 1891 the systematic expulsion of most of the Jews from Moscow began. [...] The (col. 444)

police strictly applied the discriminatory laws, and the expulsion of Jews from towns and villages where they had lived peacefully during the reign of Alexander II was effected, either under the law or with the help of bribery, to become a daily occurrence. The press (which was subjected to severe censorship) conducted a campaign of unbridled [[uncontrolled]] anti-Semitic propaganda. K. *Pobedonostsev, the head of the "Holy Synod" (the governing body of the Russian Orthodox Church), formulated the objectives of the government when he expressed the hope that "one-third of the Jews will convert, one-third will die, and one-third will flee the country.">

(Russia, col. 445)

[[Here finally is presented the main element of Russian Antisemitism: the criminal Russian Orthodox "Christian" Church which was leading the Czarist apparatus]].

<In 1891 the expulsion of Jews from *Moscow was effected, an event that alarmed Jews throughout the country for they saw it as a reaffirmation of the Pale of Settlement policy.>

(History, col. 735)

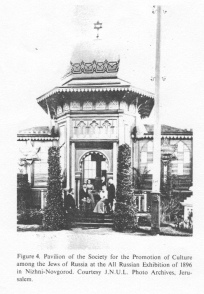

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 441, pavilion of the Society for the Promotion of Culture among

the Jews of Russia at the All Russian Exhibition of 1896 in Nizhni-Novgorod

[1897: Population figures of the census]

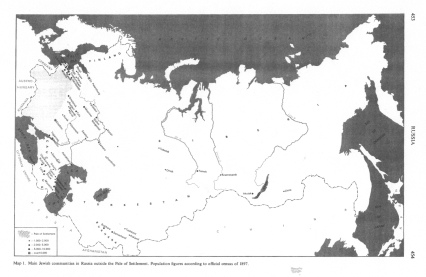

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 453-454, map of the main Jewish communities in Russia outside

the Pale of Settlement. Population figures according to official census 1897

<JEWISH POPULATION AT THE CLOSE OF THE 19TH CENTURY.

The comprehensive population census of 1897 provides a general picture of the demographic and economic condition of Russian Jewry at the close of the 19th century. In the census 5,189,400 Jews were counted; they constituted 4.13% of the total Russian population and about one-half of world Jewry. Their distribution over the Russian Empire was as follows:

Table 2 [Jews in Russian Empire 1897]

Region

Number of Jews

% of total population

Ukraine, Bessarabia

2,148,059xxx

9.3%

Lithuania, Belorussia

1,410,001xxx 14.1%

Russian Poland

1,316,576xxx 14.1%

Total in Pale of Settlement

4,874,636xxx 11.5% (93.9% of the Jews in Russia)

Interior of Russia, Finland

208,353xxx 0.34%

Caucasus

58,471xxx 0.63%

Siberia, Russian Central Asia

47,941xxx 0.35%

(the Jews of Bukhara excluded)

5,189,401xxx 4.13%

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14, col. 450

In certain provinces of the Pale of Settlement the percentage of Jews rose above their general proportion (18.12% in the province of Warsaw; 17.28% in the province of Grodno). The overwhelming majority of the Jews in the Pale lived in towns (48.84%) and townlets (33.05%). Only 18.11% lived in villages. The Jews of the villages nevertheless numbered about 890,000.

A decisive factor in the social pattern of Russian Jewry was its concentration in the towns and townlets. The townlet (see *shtetl) - a legacy of the social structure of ancient Poland - was a center of commerce and crafts for the neighboring villagers and its population was mostly Jewish. There Jewish tradition, cohesion, and folkways were well preserved, serving as the basis and starting point for both the conservative and innovative forces in Jewish culture. In the larger cities the majority of the Jews also resided in the same locality and led their own social life. (col. 450)

In 1897 the largest communities of Russia were the following:

Table 3 [Numbers and percentage of Jews in Russian towns 1897]

City

Number of Jews

% of total population

Warsaw

-

32.5%

Odessa

-

34.65%

Lodz

-

31.7%

Vilna

-

45.4%

Kishinev

-

46.3%

Bialystok

47,783

75.8%

Minsk

47,562

52.3%

Berdichev

-

80.0%

Yekaterinoslav ((Dnepropetrovsk)

-

36.3%

Vitebsk

-

52.4%

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14, col. 451 There were also many medium-sized towns in which the majority of the population was Jewish.

ECONOMIC STRUCTURE. [Professions according to the census 1897]

This concentration of the Jews, and their intensive and variegated cultural life, made them a clearly distinct nation living in the Pale of Settlement. Their occupations and professional structure also gave a specific character to their society. In 1897 the Jews of Russia could be divided according to their sources of livelihood as follows:

Table 4 [Professions of the Jews in Russia 1897]

Occupation

%

Commerce

38.65%

Crafts and industry

35.43%

Domestics and daily workers

6.61%

Liberal professions and administration

5.22%

Transport

3.98%

Agriculture

3.55%

Army

1.07%

Without regular source of livelihood

5.49%

100.00%

from: Russia; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 14, col. 451

In the Pale of Settlement Jews formed 72.8% of those engaged in commerce, 31.4% of those engaged in crafts and the close of the 19th century the Jewish proletariat increased and numbered some 600,000. Approximately half of them were apprentices and workers employed by craftsmen, about 100,000 were salesmen, about 70,000 were factory workers, and the remainder daily workers, porters, and domestics.

The desire of this proletariat to improve its material and social status, and its contacts with the revolutionary Jewish intelligentsia during the generation which preceded the 1917 Revolution, became an important factor in the lives of the Jews of Russia.> (Russia, col. 451)

[1894-1918: anti-Semitic agitation under czar Nicholas II - pogroms, police protects the rioters]

<This [[anti-Semitic]] policy was also continued under [[the next czar]] *Nicholas II (1894-1918). In reaction to the growth of the revolutionary movement, in which the radicalized Jewish youth took an increasing part, the government gave free rein [[gave the way free]] to the anti-Semitic press and agitation. During Passover, in 1903, a pogrom broke out in *Kishinev

in which many Jews lost their lives. From then on pogroms became a part of government policy. They gained in violence in 1904 (in Zhitomir) and reached their climax in October 1905, immediately after the czar had been compelled to proclaim the granting of a constitution to his people.

<[The direct link from the racist Czar to the anti-Semitic rowdy organization "Black Hundreds"]

[[Since 1882]] the situation continued to deteriorate to such a degree that in the next reign Czar *Nicholas II gave money to the anti-Semitic organization, the Black Hundreds, and made no secret of his personal membership, and that of the crown prince, in that organization (see *Union of Russian People). This body was associated with the government in directly fomenting pogrms durnig the revolutionary years of 1903 and 1905.>

(from: Encyclopaedia Judaica: Anti-Semitism, vol. 3, col. 123)

In these pogroms the police and the army openly supported the rioters and protected them against the Jewish *self-defense (see below). Pogroms accompanied by bloodshed in which the army actively participated occurred in *Bialystok (June 1906) and *Siedlce (September 1906).>

(Russia, col. 446)

[[In this anti-Jewish atmosphere racist Zionism is coming up with the false hope for a peaceful "Jewish state" in Palestine, but the Arabs are never asked, and the Jews world wide are not taken earnest, and the czar does not seem having been told to stop anti-Semitic agitation by his German noble friends of racist kaiser Emperor Wilhelm...]]

<In 1903 there occurred a massacre in *Kishinev that set off a wave of anti-Jewish violence. The ruling circles also made great efforts to involve the Poles in these outbreaks. They were successfully in *Bialystok.>

(History, col. 735)

[Jewish self-defense since the pogroms of 1903]

When the new wave of pogroms broke out in Russia in 1903, Jewish youth reacted by a widespread organization of (col. 452)

self-defense. Defense societies of the Bund, the Zionists, and the Zionist-Socialists were formed in every town and townlet. The attackers encountered armed resistance. The authorities who secretly supported the pogroms, were compelled to appear openly as the protectors of the rioters. The principal motives for the self-defense movement were not only the will to protect life and property but also the desire to assert the honor of the Jewish nation. (col. 455).

[1905 revolution and installation of the Duma]

[[There is no text about the 1905 revolution, but photos of Jewish victims, racist Zionist Jewish self-defense, and Jewish Duma deputies of 1906]]:

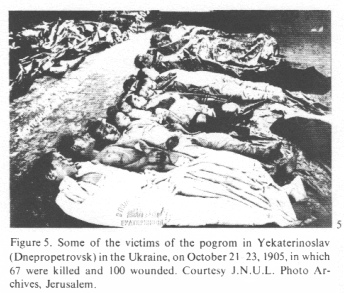

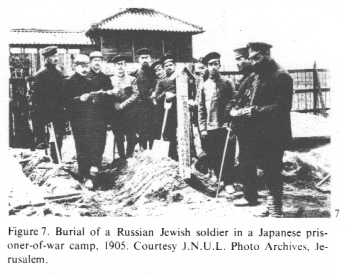

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 445: Jewish pogrom dead victims in Dnepropetrovsk, 1905: Some of the victims of the pogrom in Yekaterinoslav (Dnepropetrovsk) in the Ukraine, on October 21-23, 1905, in which 67 were killed and 100 wounded. Courtesy J.N.U.L. Photo Archives, Jerusalem Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 445-446: Burial of a Russian Jewish soldier in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, 1905. Courtesy J.N.U.L. Photo Archives, Jerusalem. Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 445: [[racist]] Zionist self-defense group from Odessa, 1905. Courtesy A. Rafaeli-Zenziper, Archive for [[racist]] Russian Zionism, Tel Aviv.

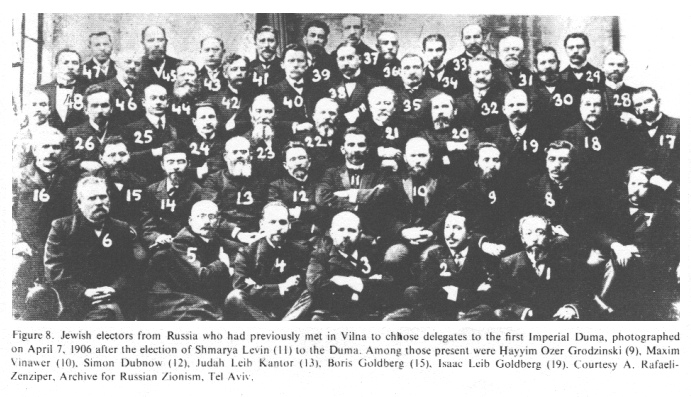

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 445-446: Jewish delegates for the Duma of 1906

Jewish electors from Russia who had previously met in Vilna to chose delegates to the first Imperial Duma, photographed on April 7, 1906 after the election of Shmarya Levin (11) to the Duma. Among those present were Hayyim (Ḥayyim) Ozer Grodzinsky (9), Maxim Vinawer (10), Simon Dubnow (12), Judah Leib Kantor (13), Boris Goldberg (15), Isaac Leib Goldberg (19). Courtesy A. Rafaeli-Zenziper, Archive for [[racist]] Russian Zionism, Tel Aviv.

[Imperial Duma with Jews - the right parties call for the "elimination of the Jews"- Duma rejecting the abolition of Pale of Settlement - but maintaining military service for Jews - but no Jews as officers (1912) - blood libel process (1913)]

<The establishment of the Imperial Duma brought no change to the situation of the Jews. There was indeed a limited Jewish representation in the Duma (12 delegates in the first Duma of 1906 (col. 446)

and two to four delegates in the second, third, and fourth Dumas), but this representation was faced by a powerful Rightist party - the *Union of the Russian People - and related parties, whose principal weapon in the political struggle against the liberal and radical elements was a savage anti-Semitism which overtly called for the elimination of the Jews from Russia.

[[All this anti-Semitic agitation is backed by the criminal Orthodox church of Russia, and there was never an excuse for this]].

It was these circles which produced the "Protocols of the *Elders of Zion" which served, and still serve, as fuel for anti-Semitism throughout the world.

[[These protocols say that there is a world wide Jewish net against all other religions. But every religion has it's world wide net, above all the criminal "Christian" religion with it's wars under a "holy" cross]].

In this atmosphere a proposal for a debate in the Duma on the abolition of the Pale of Settlement was shelved [[rejected]], while a suggestion to exclude the Jews from military service was not accepted for the sole reason that the government could not dispense with the service of about 40,000 Jewish soldiers.

Characteristic of this period was the law issued in 1912 which prohibited the appointment as officers not only of apostates from Judaism, but also of their children and grandchildren.> (Russia, col. 449)

<In 1912 an anti-Jewish *boycott was organized in Warsaw. Thus Russian Jews were faced by the menace of *pogroms, i.e., constant physical assault and robbery; these were certainly abetted by the authorities, and - as the official archives showed, when opened after the revolution of 1917 - in many cases organized by police functionaries and financed by societies close to the government. Jews reacted against this situation by the creation of *self-defense organizations, a pattern of behavior which continued until the period of the pogroms under *Petlyura, Makhno, and *Denikin during the civil war after the Revolution of 1917.> (History, col. 735)

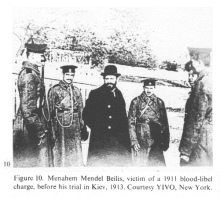

<In 1913 the [[racist "Christian" czarist]] government held a blood libel trial in Kiev involving Mendel *Beilis:

Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 447-448, Menahem Mendel Beilis,

victim of a 1911 blood-libel charge, before his trial in Kiev, 1913

the anti-Semitic propaganda was intensified and the government mobilized its police and judicial cadres to obtain [[get proofs about]] his conviction. A strong defense was mustered, including the Jews O. *Gruzenberg and Rabbi J. *Mazeh, which succeeded in disproving the libel: the jury, consisting of 12 Russian peasants, acquitted [[discharged]] the accused.> (Russia, col. 449)

[Anti-Semitism and pogroms are provoking emigration - foundation of the Jewish Colonization Association ICA]

<The pogroms, restrictive decrees, and administrative pressure caused a mass emigration of Jews from Russia, especially to the United States. During 1881 to 1914 about 2,000,000 Jews left Russia. This emigration did not result in a decrease in the Jewish population of the country as the high birthrate recompensed the losses through emigration. The economic situation improved however because the pressure on the sources of livelihood did not grow at its former pace and also because the emigrants rapidly began to send financial assistance to their relatives in Russia.> (Russia, col. 449)

[[In some regions also boycott movements were organized against the Jews which lasted for years and caused heavy impoverishment of big parts of the Jewish population, see: *Boycotts, anti-Jewish. This was 30 years before Hitler came and is not mentioned in any school book at all. The emigration must have pleased the racist "Christian" czar: The help for the Jews came by the Jews themselves and he did nothing. Later in 1918-1919 also the racist Zionists were within the emigrants and building up their Zionist center in New York]].

Several attempts were made to organize and regulate this continual emigration, the most important by the Jewish philanthropist Baron Maurice de *Hirsch who reached an agreement in 1891 with the Russian government on the transfer of 3,000,000 Jews within 25 years to Argentina. For this purpose, the *Jewish Colonization Association (ICA) was established. Even though the project was not realized, ICA was very active in promoting Jewish agricultural settlement both in the lands of emigration and in Russia itself [[partly together with the Joint]].> (Russia, col. 449)

[[Here is the text from the article "History" about the same Jewish emigration wave 1881-1914]]:

<The Jews of the Pale of Settlement and Galicia and Austria reacted to the straitened economic circumstances, even more strongly than to the wave of unprecedented hatred and violence in Russia, by mass emigration. Between 1881 and 1914 over 2 1/2 million emigrated from Eastern Europe (c. 80,000 annually), over two million of them to the United States, creating the great Jewish center there. Over 350,000 settled in Western Europe; centers of Jewish tailoring and trade in England and in other countries were created by this emigration, since a large proportion of the Jews were tailors and many who formerly had no profession joined their ranks.

Many others turned to peddling. The "greenhorns" were unacquainted with the language and culture of the new country and dependent to a large degree on economic help and spiritual help from earlier arrivals. They clustered together, thus creating "ghettos" in the great cities of the east coast of the United States and in Western Europe. These were at first islands of Eastern European Jewish culture and way of life, where Yiddish was spoken and *Yiddish literature, newspapers, theaters, and journalism burgeoned amidst the surrounding cultures.

For the second generation, the traditions of learning and respect for intellectual activities and the free professions pointed to intensive study and the acquirement of a profession as the way to social betterment. This naturally entailed deep acculturation. The dynamics of traditional Jewish culture in an open and more or less tolerant society created the present broad strata in Jewry of those occupied (col. 735)

in the free professions, of the intelligentsia, writers, artists, and newspapermen in the United States and other Western countries. The children and grandchildren of the poor and hard-working immigrant parents, who at first labored in the grueling atmosphere of the "sweat shops" "pulled themselves up by their own boot straps" thanks to a tradition that took the road of learning and social leadership and service wherever and whenever permitted.

The present situation, where the vast majority of Jewish youth enters the universities and other academic institutions, can be interpreted as being no less the result of an acceleration of immanent Jewish trends than a part of the present general trend toward academic education. The vestiges of occupations such as tailoring and peddling are rapidly disappearing. Productivization has taken a different and unexpected turn in modern Jewish society in the West.> (History, col. 736)

<IDEOLOGICAL TRENDS. [Radical Jewish movements as an answer to the czarist discrimination regime: Jewish workers party Bund - or Zionism]

The last 20 years of the czarist regime were a time of tension and renaissance for the Jews especially within the younger circles. This awakening essentially stemmed from conscious resistance to, and rejection of, the oppressive regime, the degrading status of the Jew in the country, and the search for methods for change.

Social-Democrats: One response to the oppressive policy of the czarist government was to join one of the trends of the Russian revolutionary movement. The radical Jewish youth joined clandestine organizations in the towns of Russia and abroad. Many Jews ranked among the leaders of the revolutionaries. The leaders of the Social-Democrats included (Russia, col. 451)

J. *Martov and L. *Trotsky, while Ch. *Zhitlowski and G.A. *Gershuni figured among the founders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party of Russia. With the growth of national consciousness in revolutionary circles at the close of the 19th century, a Jewish workers' revolutionary movement was formed.

Bund: Workers' unions which had been founded through the initiative of Jewish intellectuals united and established the *Bund in 1897. The Bund played an important role in the Russian revolutionary movement in the Pale of Settlement. It regarded itself as part of the all-Russian Social-Democratic Party but gradually came to insist upon certain national demands such as the right to cultural autonomy for the Jewish masses, recognition of Yiddish as the national language of the Jews, the establishment of schools in this language, and the development of the press and literature. The Bund was particularly successful in Lithuania and Poland, where after a short time it raised the social status of the worker and the apprentice, and implanted in them the courage to stand up to their employers and the authorities.

[Racist] Zionism: Another response of the Jews to their oppression in Russia found expression in the [[racist]] Zionist movement. Zionism originated in the *Hibbat Zion movement which came into being after the pogroms of 1881-83 (see also Leon *Pinsker). A few of the hundreds of thousands of Jews who left for overseas turned toward Erez Israel and established the first settlements there. Hovevei Zion societies in Russia propagated the idea of this settlement and raised funds for its maintenance. The movement gained great impetus with the appearance of Theodor *Herzl, the convention of the First Zionist Congress in Basle, and the founding of the World Zionist Organization (1897).

Due to the political regime of Russia, the central institutions of the Zionist Organization were established in Western Europe, even though the mass of its members and influence came from Russian Jewry. Zionism won adherence among all Jewish groups: the Orthodox and maskilim [[followers of the Haskalah, enlightenment Jews, secularists]], the middle class and proletariat, the youth and intelligentsia. It encouraged national thought and culture among the masses. The Zionist press (*Haolam; Razsvet, etc.) and Zionist literature in three languages - Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian - gained wide popularity.

The movement was illegal and the attitude of the government ranged from one of reserve, seeing that the movement could divert the Jewish youth from active participation in the revolutionary movement, to one of hostility. Zionist congresses and meetings were held openly (Minsk, 1902) and clandestinely. The failure of Herzl to obtain a charter from the Turkish sultan and the debate over the *Uganda project resulted in a grave crisis within the Zionist movement in Russia. Herzl largely based his case for accepting the Uganda project on the urgent need for a "Nachtasyl" [["night asylum"]] for the suffering Russian Jews, but it was the majority of the Russian Zionists, led by M. *Ussishkin and J. *Tschlenow, who on principle opposed the Uganda proposal.

Some of the proposal's supporters later resigned from the Zionist movement and founded territorialist organizations (see *Territorialism), the most important of which was the *Zionist Socialist Workers' Party (S.S.). Immigrants and pioneers from Russia formed the greater part of the Second *Aliyah and it was from their ranks that the founders of the labor movement in Erez Israel emerged.

[The effect of the extreme Jewish movement on the Jewish youth]

Within a relatively short period, the revolutionary movement and the Zionist movement brought a tremendous change among Jewish youth. The battei-midrash [[House of Learning]] and yeshivot [[religious Torah school]] were abandoned, and dynamism of Jewish society now became concentrated within the new political trends. (Russia, col. 452)

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS. [Writers and researchers]

The nationalist awakening was also expressed by an astonishing development of Jewish literature in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian. A continuation of the Haskalah literature, it reached its peak during the generation which preceded the 1917 Revolution.

The most outstanding authors of that period were

*Ahad Ha-Am,

M.J. *Berdyczewski,

M.Z. *Feuerberg,

the Hebrew poets

H.N. *Bialik,

Saul *Tchernichowsky,

Z. *Shneour and others,

as well as the Jewish Russian poet S.S. *Frug

and the Yiddish writers

*Shalom Aleichem,

I.L. *Peretz,

and Sholem *Asch.

There also arose a generation of researchers and historians, the most important of whom was S. *Dubnow, who wrote his History of the Jews and based his historical and world view on *Autonomism. Systematic research into Jewish folklore was started upon (S. *An-Ski). A Jewish encyclopedia in Russian was published (Yevreyskaya Entsiklopediya; 1906-13).

[New Jewish organizations and institutions founded since the pogroms of 1881]

The existing and new societies - Hevrat Mefizei Haskalah, *ORT, *OSE, ICA - became frameworks for the activity of members of the Jewish intelligentsia who sought to extend the scope of these societies as far as possible. Jewish newspapers circulated in hundreds of thousands of copies. The mass of Jews read the daily press in Yiddish (Der Fraynd; *Haynt; Der *Moment; etc.); Hebrew readers turned to the Hebrew press (*Ha-Zefirah; *Ha-Zofeh; Ha-Zeman); others read the Russian-Jewish press. In St. Petersburg the foundations were laid for a Higher School of Jewish Studies by Baron D. *Guenzburg, and in Grodno a teachers' seminary, which trained teachers for the Jewish national schools, was opened under the patronage of the Hevrat Mefizei Haskalah.

[Split Jewish intellectuals between Yiddish and Hebrew]

An important point at issue that developed between the [[racist]] Zionists and their opponents was the character of Jewish culture. The Bund and Autonomist circles considered that the future of the Jews lay as a nation among the other nations of Russia; they sought to liberate it from religious tradition and to develop a secular culture and national schools in the language of the masses - Yiddish. The Zionists ant their supporters stressed the continuity and the unity of the Jewish nation throughout the world and regarded Hebrew as the national language of the Jewish people. They considered the deepening of Jewish national consciousness and attachment to the historical past and homeland - Erez Israel - to be the primary aim and mainstay of Jewish culture. This controversy grew acute after the Yiddishists had proclaimed Yiddish to be a national language of the Jewish people at the *Czernowitz Yiddish Language Conference in 1908. The "language dispute" was fought with bitter animosity and caused a split within the Jewish intelligentsia of Eastern Europe.> (Russia, col. 455)

[[Later the Zionists were keen to be dominant in Erez Israel and banned Yiddish from the media landscape which stayed in Russia and New York but died out by Zionist and communist annihilation tactics]].

| Teilen / share: |

Facebook |

|

Twitter

|

|

|

|

Further sources

[1] http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narodnaja_Wolja

^

![Encyclopaedia Judaica (1971):

Russia, vol. 14, col. 445: [[racist]] Zionist

self-defense group from Odessa, 1905. Courtesy

A. Rafaeli-Zenziper, Archive for [[racist]]

Russian Zionism, Tel Aviv. Encyclopaedia

Judaica (1971): Russia, vol. 14, col. 445:

[[racist]] Zionist self-defense group from

Odessa, 1905. Courtesy A. Rafaeli-Zenziper,

Archive for [[racist]] Russian Zionism, Tel

Aviv.](EncJud_Russia-d/EncJud_Russia-band14-kolonne445-zionistische-selbstverteidigung-Odessa1905.jpg)