[since 1624: Ghetto under

Ferdinand II - 1635: walking rights - hospitals -

refugees from Chmielnicki massacres]

They suffered during the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) as a

result of the occupation of the city by Imperial soldiers.

In 1624 Emperor *Ferdinand II confined the Jews to a

ghetto situated on the site of the present-day

Leopoldstadt quarter. In 1632 there was were 106 houses in

the ghetto, and in 1670 there were 136 houses

accommodating 500 families.

A document of privilege issued in 1635 authorized the

inhabitants of the ghetto to circulate within the "inner

town" during business hours and Jews also owned shops in

other streets of the city. Some Jews at this time were

merchants engaged in international trade; others were

petty traders.

|

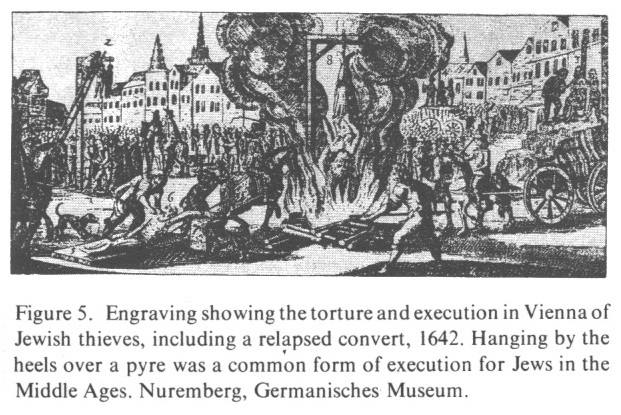

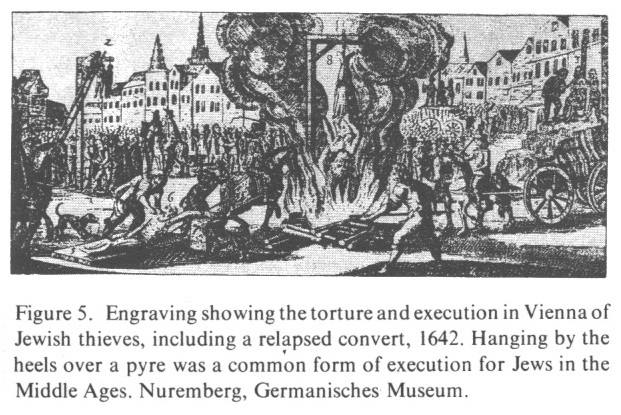

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Vienna, vol.16,

col.129, death penalty by hanging and fire for

Jewish criminals in 1642: Engraving showing the

torture and execution in Vienna of Jewish

thieves, including a relapsed convert, 1642.

Hanging by the heels over a pyre was a common

form of execution for Jews in the Middle Ages.

Nuremberg, Germanic Museum ("Germanisches

Museum") |

The community of Vienna reassumed its respected position

in the Jewish world. In addition to other communal

institutions they maintained two hospitals. Among rabbis

of the renewed community were Yom Tov Lipman Heller, and

Shabbetai Sheftel *Horowitz, one of the many refugees from

Poland who fled the *Chmielnicki massacres of 1648.

[1669: Expulsion of the

Jews under Leopold I - no arrangement possible - some

conversions]

Hatred by the townsmen of the Jews increased during the

mid-17th century, fanned by the bigotry of Bishop

Kollonitsch. Emperor Leopold I, influenced by the bishop

as well as the religious fanaticism of his wife, and

sustained by the potential gains for his treasury, decided

to expel the Jews from Vienna once again. Though Leo

*Winkler, head of the Jewish community at the time,

arranged for the intervention of Queen Christina of Sweden

on behalf of the Jews it was of no avail, as was an offer

to the emperor of 100,000 florins to limit the expulsion.

The poorer Jews were expelled in 1669; the rest were

exiled in the month of Av, 1670, and their properties

taken from them.

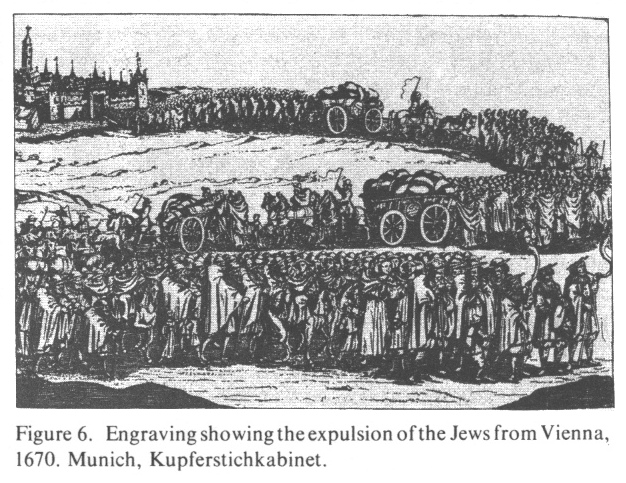

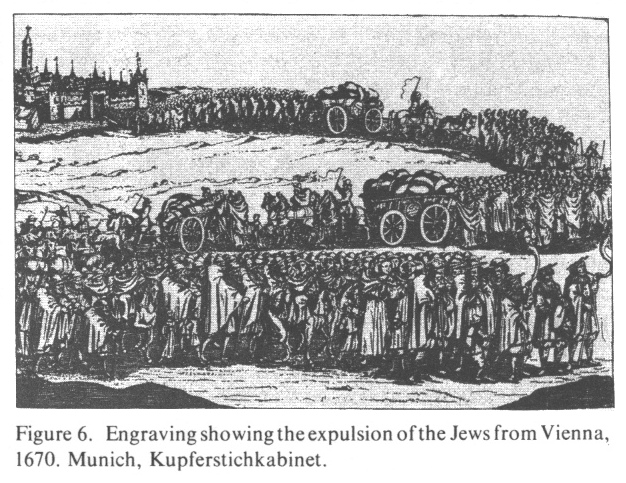

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Vienna, vol.16, col.129,

expulsion and treck in 1670: Engraving showing the

expulsion

of the Jews from Vienna, 1670. Munich, print room

("Kupferstichkabinett")

The Great Synagogue was converted into a Catholic church,

the "Leopoldskirche". The Jews paid the municipality 4,000

florins to supervise the Jewish cemetery. Of the

3,000-4,000 Jews expelled some made their way to the great

cities of Europe where a number succeeded in regaining

their fortunes. Others settled in small towns and

villages. According to the testimony of the Swedish

ambassador at the time, some of the Jews took advantage of

the offer to convert to Christianity so as not to be

exiled.

[1693: Rich Jews allowed

to settle in Vienna - high taxation]

By 1693 the financial losses to the city were sufficient

to generate support for a proposal to readmit the Jews.

This time, however, their number was to be much smaller,

without provision for an organized community. Only the

wealthy were authorized to reside in Vienna, as "tolerated

subjects", in exchange for a payment of 300,000 florins

and an annual tax of 10,000 florins. Prayer services were

permitted to be held only in private homes. The founders

of the community and its leaders in those years, as well

as during the 18th century, were prominent *Court Jews,

such as Samuel *Oppenheimer, Samson *Wertheimer, and Baron

Diego *Aguilar.

As a result of their activities, Vienna became a center

for Jewish diplomatic efforts on behalf of Jews throughout

the empire as well as an important center for Jewish

philanthropy. In 1696 Oppenheimer regained possession of

the Jewish cemetery and built a hospital for the poor next

to it.

[Hierosolymitian

foundation for Jews in Palestine 1742-1918 - Sephardi

community since 1737]

The wealthy of Vienna supported the poor of Erez Israel;

in 1742 a fund of 22,000 florins was established for this

purpose, and until 1918 the interest from this fund was

distributed by the Austrian consul in Palestine (see

*Hierosolymitanische Stiftung [[Hierosolymitian

foundation]]). A Sephardi community in Vienna traces its

origins to 1737, and grew as a result of commerce with the

Balkans.

[Anti-Semitic legislation

under Maria Theresa 1740-1780 - Toleranzpatent under

Joseph II since 1781 - Hebrew printing press since 1793]

During the 18th century the restrictions on the residence

rights of the "tolerated subjects" had prevented the rapid

growth of the Jewish population in Vienna. There were 452

Jews living in the city in 1752 and 520 in 1777. The Jews

suffered under the restrictive legislation of *Maria

Theresa (1740-80). In 1781 their son, Joseph II, issued

his *Toleranzpatent, (col. 123)

which though attacked in Jewish circles, paved the way in

some respects for later emancipation. Religious studies

and sermons were delivered illegally by the scholars of

the community or by rabbis who had been called upon to

visit the town.

By 1793 [[Napoleon time]] there was a Hebrew printing

press in Vienna that soon became the center for Hebrew

printing in Central Europe (see below). During this period

the first signs of assimilation in the social and family

life of the Jews of Vienna made their appearance, and

there was a decline in the observance of tradition.>

(col. 124)

|

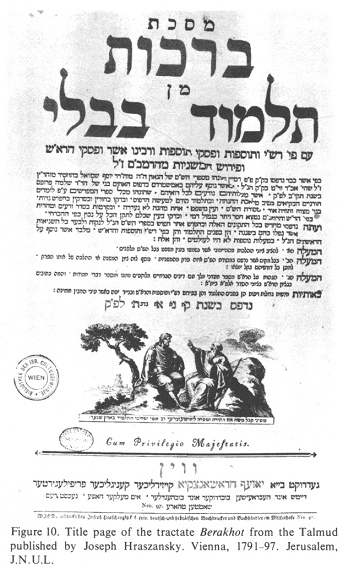

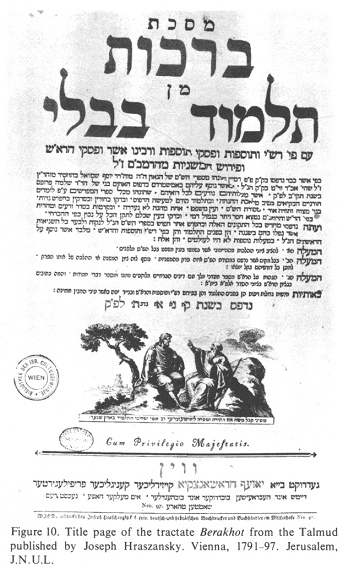

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Vienna, vol.16,

col.130, Talmud 1797: Title page of the tractate

"Berakhot" from the Talmud published by Joseph

Hraszansky. Vienna, 1791-97. Jerusalem, J.N.U.L. |

<Hebrew Printing.

In the 16th century a number of books were published

in Vienna which had some rough Hebrew lettering (from

wood-blocks?):

-- Andreas Planeus' Institutiones Grammatices Ebreae,

printed by Egyd Adler, 1552

-- J.S. Pannonicis' De bello tureis in ferendo, printed by

Hanns Singriener, 1554

-.- and Paul Weidner: Loca praecipuo Fidei Christianae,

printed by Raphael Hofhalter, 1559.

Toward the end of the 18th century extensive Hebrew

printing in Vienna began with the court printer Joseph

Edler von Kurzbeck, who used the font of Joseph *Proops in

Amsterdam. He employed Anton (later: von) Schmid

(1775-1855), who chose printing instead of the priesthood.

Their first production was the Mishnah (1793). In 1800 the

government placed an embargo on Hebrew books printed

abroad and thus gave him a near monopoly. His correctors

were Joseph della Torre and the poet Samuel Romanelli (to

1799), who with Schmid printed his

Alot ha-Minah for

Charlotte Arnstein's fashionable marriage (1793).

Among the works they printed were a Bible with

Mendelssohn's

Biur

(1794-95) and David Franco-Mendes'

Gemul Atalyah (1800).

Schmid also issued the 24th Talmud edition (1806-11) and

the

Turim

(1810-13) with J.L. Ben-Zeev's notes on

Hoshen Mishpat.

Besides Kurzbeck and Schmid there were other rivals and

smaller firms: Joseph Hraszansky, using a Frankfort on the

Main font, opened a Hebrew department in Vienna. Among his

great achievements are an edition of the Talmud (1791-97).

In 1851 "J.P. Sollinger's widow" began to print Hebrew

texts including a Talmud, with I.H. *Weiss as corrector

(1860-73). Special mention must also be made of the Hebrew

journals printed in Vienna including

*Bikkurei ha-Ittim (1820/21-31),

Kerem Hemed

(1833-56),

Ozar Nehmad

(1856-63),

Bikkurei

Ittim (1844),

Kokhevei

Yizhak (1845-73), and

Ha-Shahar (1868-84/5).> (col. 131)

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Vienna, vol. 16, col. 122

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Vienna, vol. 16, col. 122