[Vienna Congress 1815:

The Jewish rights after the partly emancipation of the

Jews under Napoleon are not renewed]

VIENNA, CONGRESS OF,

international congress held in Vienna, September 1814 to

June 1815, to reestablish peace and order in Europe after

the Napoleonic Wars. the congress met in the Apollosaal

[[Apollo hall]] built by the English-born Jew, Sigmund

Wolffsohn, and the delegates were often entertained during

the course of the proceedings in the (col. 131)

*salons of Jewish hostesses, such as Fanny von *Arnstein

and Cecily *Eskeles.

The Jewish question, raised explicitly for the first time

at an international conference, arose in connection with

the constitution of a new federation of German states. The

Jews of Frankfort and of the Hanseatic towns of *Hamburg,

*Luebeck, and *Bremen had previously attained equal civil

rights under French rule. The Hanseatic cities were

annexed to France in 1810, and Jewish emancipation in

France was effective ipso facto there. The Frankfort

community paid the French staff of the duke a vast sum of

money in 1811 in return for being granted equality. They

now sent delegates to the Congress to seek confirmation of

their rights, as well as emancipation for the Jews of the

other German states.

The delegates for Frankfort were Gabriel Oppenheimer and

Jacob Baruch (the father of Ludwig *Boerne), while the

Hanseatic towns were represented among others, by the

non-Jew Carl August *Buchholz. They succeeded in gaining

the support of such leading personalities as Metternich

(Austria), Hardenberg, and Humboldt (Prussia). In October

1814 a committee of five German states met to prepare

proposals for the constitution of the new federation.

Bavaria and Wuerttemberg, fearing the curtailment of their

independence, opposed Austria, Prussia, and Hanover,

specially on the question of Jewish rights.

At the general session of the Congress in May 1815, the

opposition to Jewish civil equality grew, despite

favorable proposals by Austria and Prussia. On June 10,

paragraph 16 of the constitution of the German Federation

was resolved:

The Assembly of the

Federation will deliberate how to achieve the civic

improvement of the members of the Jewish religion in

Germany in as generally agreed a form as possible, in

particular as to how to grant and insure for them the

possibility of enjoying civic rights in return for the

acceptance of all civic duties in the states of the

Federation; until then, the members of this religion

will have safeguarded for them the rights which have

already been granted to them by the single states of the

Federation.

This formulation postponed Jewish equality to the far

distant future, while by changing one word in the final

draft to "by", instead of "in the states", a formulation

arrived at only at the meeting on June 8, a loophole had

been left by which the states could disown rights granted

by any but the lawful government, namely, those bestowed

by the French or their temporary rulers. The Congress,

therefore, did nothing to better the status of the Jews

but, in effect, only worsened their position in many

places.

The Jewish question arose again at the Conference of

Aix-la-Chapelle (1818), when the powers met to determine

the withdrawal of troops from France and consider France's

indemnity to the allies. Various Jewish communities turned

to the conference for relief, and Lewis *Way, an English

clergyman, presented a petition for emancipation to

Alexander I of Russia. Despite a sympathetic reception,

however, there were no practical results.

Bibliography:

M. J. Kohler, in: AJHSP, 26 (1918), 33-125

-- L. Wolf: Notes on the Diplomatic History of the Jewish

Question (1919), 12-15

-- S.W. Baron: Die Judenfrage auf dem Wiener Kongress

(1920)

-- M. Grunwald: Vienna (1936), 190-204.

[S.ETT.]> (col. 132)

[since 1815: Emancipation

of the Jews in Vienna step by step - Haskalah and flow

of Jews from Galicia - new generation of Jewish

intellectuals]

At the time of the Congress of Vienna in 1815 (see

*Vienna, Congress of) the salons of Jewish hostesses

served as entertainment and meeting places for the rulers

of Europe. In 1821 nine Jews of Vienna were raised to the

nobility.

From the close of the 18th century, and especially during

the first decades of the 19th, Vienna became a center of

the *Haskalah movement. The influence and scope of the

community's activities increased particularly after the

annexation of *Galicia by Austria.

Despite restrictions, the number of Jews in the city

rapidly increased. Several Hebrew authors, including the

poet and traveler Samuel Aaron *Romanelli, the philologist

Judah Leib *Ben-Zeev, the poet Solomon Levisohn, Meir

*Letteris, etc., wrote their works in Vienna. Some of them

earned their livelihood as proofreaders in the city's

Hebrew press. The character of Haskalah and the literature

of the Jews of Vienna was gradually Germanized. There

emerged a generation of intellectuals, such as Ludwig

August *Frankl, Moritz *Hartmann, Leopold *Kompert, and

Ignaz *Kuranda, that did not know Hebrew. The first Jewish

journalists, such as Isidor Heller, Moritz Kuh, and

Zigmund Kulischer, inaugurated an era of Jewish influence

on the Viennese press.

[Inner Jewish struggle

about religious reforms in Vienna - Isaac Noah

Mannheimer]

At a later period the call for religious reform was heard

in Vienna. Various

maskilim,

including Peter Peretz *Ber and Naphtali Hertz *Homberg,

tried to convince the government to impose Haskalah

recommendations and religious reform on the Jews. This

aroused strong controversy among the Vienna community. The

appointment of Isaac Noah *Mannheimer as director of the

religious school in 1825 was a compromise between the

supporters of reform and its opponents.

In 1826 a magnificent synagogue, in which the Hebrew

language and the traditional text of the prayers were

retained, was inaugurated. It was the first legal

synagogue to be opened since 1671. Mannheimer and the

hazzan [[cantor]]

Solomon *Sulzer tried to improve the decorum of the

services in the new synagogue, which became a model for

all the countries of the Austrian empire.

[1850-1920: Significant

Jewish immigration to Vienna from the eastern regions of

Austria-Hungary - figures]

During the second half of the 19th century and the first

decades of the 20th, the Jewish population of Vienna

increased as a result of immigration there by Jews from

other regions of the empire, particularly Hungary,

Galicia, and Bukovina. There were 3,739 Jews living in

Vienna in 1846, 9,731 in 1850, and about 15,000 in 1854.

After 1914 about 50,000 refugees from Galicia and Bukovina

established themselves there, so that by 1923 there were

201,513 Jews living in Vienna, which had become the third

largest Jewish community in Europe. In 1936 there were

176,034 Jews in Vienna (8% of the total population).

Jews in Vienna

|

Year

|

number of Jews

|

1846

|

3,739xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

|

1850

|

9,731xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1854

|

15,000xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1923

|

201,513xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

1936

|

176,034xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx |

Table by Michael

Palomino; from: Vienna; In: Encyclopaedia

Judaica, vol. 16, col. 124

|

The occupations of the Jews in Vienna became more

variegated. Many of them entered the liberal professions:

out of a total of 2,163 advocates, 1,345 were Jews, and

2,440 of the 3,268 physicians were Jews. Prominent as a

financier and industrialist was Moritz Pollak (1877-1904)

who was a member of the Vienna city council and president

of the Jewish community.

[Jewish outstanding

personalities and Jewish institutions before 1933]

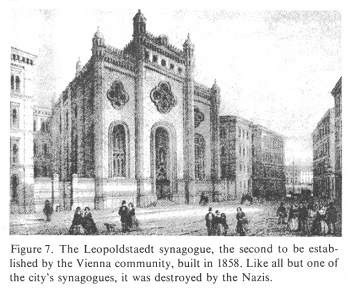

Before the Holocaust there were about 59 synagogues of

various religious trends in Vienna. There was also a

Jewish educational network. The rabbinical seminary,

founded in (col. 124)

1893, was a European center for research into Jewish

literature and history. The most prominent scholars were

M. *Guedemann, A. *Jellinek, Adolph *Schwarz, Adolf

*Buechler, David *Mueller, Victor *Aptowitzer, Z. H.

*Cahjes, and Samuel *Krauss.

There was also a "Hebrew Pedagogium" for the training of

Hebrew teachers. Many charitable and relief institutions

existed in the town, including the Rothschild Hospital and

three orphanages. Vienna also became a Jewish sports

center; the football team Ha-Koah and the *Maccabi

organization of Vienna were well known. A Jewish daily

newspaper in German,

Wiener

Morgenzeitung [[Vienna Morning Post]], was

published from 1919 to 1927.

Viennese scientists, musicians, and writers of Jewish

origin (Jews and apostates) achieved world fame, including

the authors Arthur *Schnitzler, Franz *Werfel, Richard

*Beer-Hofmann, Jakob *Wassermann, Stefan *Zweig, and Felix

*Salten, and the musicians Gustav *Mahler, and Arnold

*Schoenberg. Many Jews were actors and producers.

Scientists, researchers, and thinkers included Sigmund

*Freud, Heinrich Neumann, Joseph *Unger, and Joseph

*Popper-Linkeus. Among Jews active in general politics

were Adolf *Fischhof, Victor *Adler, Max *Adler, and Otto

*Bauer. The leading newspaper,

Neue Freie Presse, to which Theodor

*Herzl contributed, was owned in part by Jews.

|

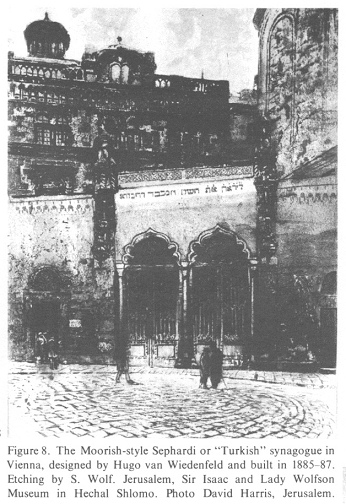

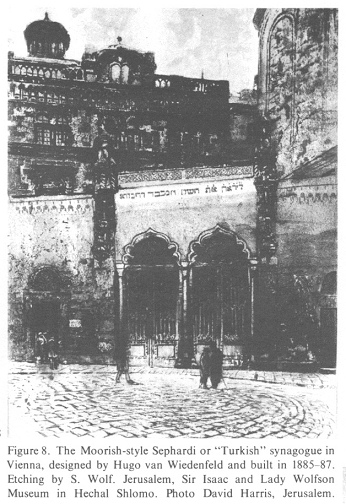

Encyclopaedia Judaica: Vienna, vol.16,

col.129, Sephardi synagogue of 1887: The

Moorish-style Sephardi or "Turkish" synagogue in

Vienna, designed by Hugo van Wiedenfeld and

built in 1885-87. Etching by S. Wolf. Jerusalem,

Sir Isaac and Lady Wolfson Museum in Hechal

Shlomo. Photo David Harris, Jerusalem. |

[Nationalism and Jewish

nationalism in Vienna - Herzl Zionism against all Arabs]

Though in the social life and the administration of the

community, there was mostly strong opposition to Jewish

national action, Vienna was also a center of the national

awakening. Peretz *Smolenskin published *Ha-Shahar between

1868 and 1885 in Vienna, while Nathan *Birnbaum founded

the first Jewish nationalist student association,

*Kadimah, there in 1882, and preached "pre-Herzl Zionism"

from 1884. It was due to Herzl that Vienna was at first

the center of Zionist activities [[provoked by the

Dreyfus

case in France. Herzl stated in his book "The Jewish

State" that an Israel could be found and all Arabs could

be driven away like the natives in the "USA", and this

would be a "modern solution" of the "Jewish question"]].

He published the Zionist movement's organ,

Die *Welt, and

established the headquarters of the Zionist Executive

there. The Zionist movement in Vienna gained in strength

after World War I. In 1919 the Zionist Robert *Stricker

was elected to the Austrian parliament. The Zionists did

not obtain a majority in the community until the elections

of 1932. Desider *Friedmann was the last president of the

community of Vienna before its destruction in the

Holocaust.

[YO.BA.]> (col. 127)

[[Supplement: The Arab

reaction on Herzl

At the same time the Arabs at once founded newspapers

against Herzl Zionism. Herzl never has been in Palestine,

has never spoken with any Arab, and 10,000s of

impoverished Jews of Eastern Europe and since 1933 German

and Austrian emigrating Jews went into the Herzl trap: the

eternal war against the Arabs of whom Zionist agitators

never had spoken. Palestinians got no voice in the UNO

until 1974, and the Herzl book is not forbidden until now

(2007). Human rights would be better. Details about Herzl

Zionism see under

Zionism...]]

[[Supplement: National

frustrations and anti-Semitism in German Austria

1871-1918 - the Austrian Hitler

There are more subjects to consider about the time between

1871 and 1918: Since 1848 (since the establishment of the

liberty of the press) the Jewish press and the national

anti-Semitic press in Austria were fighting against each

other. Since 1871 since the German victory against France

the German Austrians had the feeling that they would like

to belong to Germany because they would have liked to be

"present" in the Second Empire of Bismarck. But the

Emperor of Vienna never wanted a union with Berlin because

otherwise he had to subordinate to the German Emperor of

Berlin. Add to this after the worldwide collapse of the

stock markets in 1873 the Emperor of Vienna helped the

Jewish banks in Austria but did not help the normal

Austrian citizens, and Austria did not have an insurance

system like Bismarck's Germany had. So the anti-Semitism

in Austria was raising much since 1873 against the rich

Jews and the Jews at court in Austria without considering

that there were also many poor Jews suffering by the

economic crisis.

During World War I the Jews were serving in the army, and

Austria and Germany tried to germanize all Europe. In 1918

Austria-Hungary was split, and the Jewish politicians in

the new mini Austria were always heavily attacked by

nationals with anti-Semitism which wanted to have the

Empire back and wanted to be a member of Germany at last,

but now the French dominance in Europe prohibited the

union. Add to this also in Germany was a big frustration

now because of the loss of all colonies and of German

territories. This combination of national frustrations in

Germany and Austria at the same time was in the head of an

Austrian person which name was Adolf Hitler. He was seen

as a leader for re-establishment of "German honor" in the

world, and the German industrial leaders and the

industrial leaders of the "USA" ... supported this

criminal foreigner in Germany ... and the German police

did not act against this criminal foreigner and did not

kick him out to Austria ...]]

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Vienna, vol. 16, col. 122

Encyclopaedia

Judaica

1971: Vienna, vol. 16, col. 122