Encyclopaedia Judaica

Jews in Portugal 02:

14th and 15th century

Envy and anti-Jewish law with taxes and Jewish badge

- influx of Spanish Jews - forced conversions -

emigration movement

Encyclopaedia

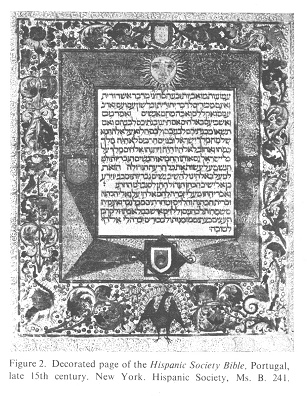

Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13, col. 923, Bible with

Hebrew letters, 15th century

from: Portugal; In: Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971, vol. 13

presented by Michael Palomino (2008)

[15th century: Jewish

factor in the state machinery - envy and actions of the

church against the Jewish rights - taxes]

<By the 15th century the Jews were playing a major role

in the country's monarchical capitalism, as that economic

system has been characterized. The concentration of Jews in

Lisbon and other population centers rendered obvious the

group's business success and - as a result of their access

to royalty - their disproportionate prominence in society.

At the same time, Portuguese Jews were fastidious in loyalty

to (col. 919)

their faith and reciprocated the distant posture assumed by

their devout Catholic neighbors, making way for the

suspicions that feed on envy. Furthermore, the independence

enjoyed by the Jewish community, in the otherwise Christian

state, aroused the ire of the clergy. Their efforts to erode

Jewish civil rights were resisted by the cultured King Diniz

(1279-1325), who retained the

arraby mor Don Judah as his treasurer and

reasserted that the Jews need not pay tithes to the church.

In any event the Jews were heavily taxed as the price of

remaining unmolested, including a special Jews' tax intended

to redeem the "accursed state of the race", and a tax based

on the number of cattle and fowl slaughtered by the

shohatim [[ritual

slaughter]].

[King Affonso IV: further

special taxes, Jewish badge, and restrictions of movement

for the Jews - criminal church blames the Jews for the

Black Death - changing kings]

The unsympathetic Affonso IV (1325-57) increased the direct

tax load to bring him an annual state income of about 50,000

livres. He also reinstituted the dormant requirement that

Jews wear an identifying yellow *badge, and restricted their

freedom to emigrate. The emboldened clergy accused the Jews

of spreading the *Black Death in 1350, inciting the populace

to action. During the short rule of Pedro I (1357-67) - who

employed as his physician the famed Moses *Navarro - the

deterioration of the Jewish position was halted.

[Protection under Affonso V

- but pogroms and "Christian" assemblies with appeals to

reduce the Jewish influence]

The situation then fluctuated from ruler to ruler until the

reign of Affonso V (1438-81), who gave the Jews his

conscientious protection, affording them a last peaceful

span of existence in Portugal.

The general populace was seething (col. 920)

with envy and religious hate. In 1449 there occurred a riot

against the Jews of Lisbon; many homes were sacked and a

number of persons were murdered. Local assemblies in 1451,

1455, 1473, and 1481 demanded that steps be taken to reduce

the national prominence of the Jew.

[1492: Influx of some

150,000 Jews from Spain - taxes for the stay under King

John II - slavery and deportations to Saint Thomas]

Somehow the Jews of Portugal never considered their

predicament as hopeless, and when *Spain expelled its Jews

in 1492, some 150,000 fled to nearby Portugal, where both

the general and Jewish culture approximated their own (see

*Spanish and Portuguese Literature). King John II (1481-95),

eager to augment his treasury, approved their admission.

Wealthy families were charged 100 cruzados for the right of

permanent residence; craftsmen were admitted with an eye to

their potential in military production. R. Isaac *Aboab was

permitted to settle with a group of 30 important families at

Oporto. The vast majority, however, paid eight cruzados per

head for the right to remain in Portugal for up to eight

months.

When this unhappy group found that a dearth of sailings made

their scheduled exit impossible, John II proclaimed them

automatically his slaves. Children were torn from their

parents, 700 youths being shipped to the African island of

Saõ Tomé (Saint Thomas) in an unsuccessful scheme to

populate this wild territory.

[King Emanuel I the

Fortunate: Marriage with Spanish princess Isabella -

anti-Semitic resolutions for expulsion - Jews are leaving

- new strategy to prevent the losses for the state -

forced baptism - emigration movement]

With the accession of Emanuel I the Fortunate (1495-1521),

the harsh distinctions between the displaced Spanish and the

native Portuguese Jews began to be erased, and hopes for a

tranquil period were raised. Instead, Emanuel's reign

signaled the end of normative Jewish life in Portugal, for

within a year of his accession he contracted a marriage with

the Spanish princess Isabella - hoping thereby to bring the

entire peninsula under a single monarch - and Spanish

royalty made its consent dependent on his ridding Portugal

of all Jews.

Consenting reluctantly, on Dec. 4, 1496, Emanuel ordered

that by November of the following year no Jew or Moor should

remain in the country. Forthright action was not taken

against the Moors, if only because Christians in Moorish

lands would then be subject to reprisals. As the departures

proceeded Emanuel reconsidered the loss of the Jewish

citizenry and the attendant economic losses. He resolved to

keep them in the country by turning the Jews into legal

Christians. He tried persuasion and torture, but with little

success, and the chief rabbi, Simon *Maimi, died resisting

conversion.

Accordingly on March 19, 1497, all Jewish minors were

forcibly baptized and detained, a move that tended to

prevent their parents from attempting to flee. The order

then went out for all who were still intent on embarkation

to assemble at Lisbon. Some 20,000 gathered there, but

instead of being evacuated they were ceremonially baptized

and declared equal citizens of the realm.

Bewildered, these *Conversos cautiously began to emigrate,

prompting Emanuel to respond on April 21, 1499, by

withholding the right of emigration from the *New

Christians, as this new class was officially designated, but

technicalities aside, the Portuguese majority continued to

regard them as Jews.> (col. 921)

Sources

|

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13,

col. 919-920 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13,

col. 921-922 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13,

col. 923-924 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13,

col. 925-926 |

Encyclopaedia Judaica 1971: Portugal, vol. 13, col. 923, Bible with Hebrew letters, 15th century